Sunday Times 2

WW III: The return of the sleepwalkers

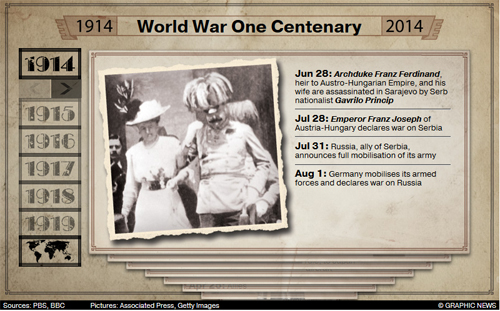

PARIS – On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were murdered in Sarajevo – triggering a series of bad decisions that culminated in World War I. A century later, the world is again roiled by conflict and uncertainty, exemplified in the Middle East, Ukraine, and the East and South China Seas. Can an understanding of the mistakes made in 1914 help the world to avoid another major catastrophe?

To be sure, the global order has changed dramatically over the last hundred years. But the growing sense that we have lost control over history, together with serious doubts about the capabilities and principles of our leaders, lends a certain relevance to the events in Sarajevo in 1914.

Only a year ago, any comparison between the summer of 1914 and today would have seemed artificial. The only parallel that could be drawn was limited to Asia: pundits wondered whether China was gradually becoming the modern equivalent of Germany under Kaiser Wilhelm II, with mounting regional tensions over China’s territorial claims resembling, to some extent, the situation in the Balkans on the eve of WWI.

In the last few months, however, the global context has changed considerably. Given recent developments in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, one could reasonably say that the entire world has come to resemble Europe in 1914.

In fact, the situation today could be considered even more dangerous. After all, a century ago, the world was not haunted by the spectre of a nuclear apocalypse. With the instruments of humanity’s collective suicide yet to be invented, war could still be viewed, as the Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz famously put it, as “the continuation of politics by other means.”

Nuclear weapons changed everything, with the resulting balance of terror preventing the Cold War’s escalation (despite several near-misses, most notably the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis). But, over time, so-called “mutual assured destruction” became an increasingly abstract concept.

Iran is now trying to convince the United States that a fundamentalist caliphate stretching from Aleppo to Baghdad poses a far greater threat than nuclear weapons. Ukraine, in its escalating conflict with Russia, seems most concerned about an energy embargo, not Russia’s nuclear arsenal. Even Japan – the only country to have experienced a nuclear attack firsthand – seems indifferent China’s possession of nuclear weapons, as it assumes an assertive posture toward its increasingly powerful neighbour.

In short, the “bomb” no longer seems to offer the ultimate protection. This shift has been driven at least partly by the global expansion of nuclear weapons. It was a lot easier to convince countries to accept a common set of rules when, despite their irreconcilable ideologies, they ultimately shared much of Western culture.

Herein lies the second fundamental difference between 2014 and 1914: Europe is no longer the center of the world. Kiev today cannot be compared to Sarajevo a century ago. A conflict that began in Europe could no longer develop into a world war – not least because much of Europe is connected through the European Union, which, despite its current unpopularity, makes war among its members unthinkable.

Given this, the real risks lie outside Europe, where there is no such framework for peace, and the rules of the game vary widely. In this context, the world’s growing angst – intensified by the memory of Archduke Ferdinand’s assassination – is entirely appropriate.

A jihadist state has emerged in the Middle East. Asian countries have begun creating artificial islands, following China’s example, in the South China Sea, to strengthen their territorial claims there. And Russian President Vladimir Putin is overtly pursuing anachronistic imperial ambitions. These developments should serve as a warning that the world cannot avoid the truth and avert disaster at the same time.

In 1914, Europe’s leaders, having failed to find satisfactory compromises, resigned themselves to the inevitability of war (some more enthusiastically than others). As the historian Christopher Clark put it, they “sleepwalked” into it. While 2014 ostensibly has little in common with 1914, it shares one critical feature: the risk that an increasingly complex security and political environment will overwhelm unexceptional leaders. Before they wake up to the risks, the situation could spin out of control.

(Dominique Moisi, a professor at L’Institut d’études politiques de Paris (Sciences Po), is Senior Adviser at The French Institute for International Affairs (IFRI). He is currently a visiting professor at King’s College London.)

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2014. Exclusive to

the Sunday Times

www.project-syndicate.org