News

No cardamom trees on Knuckles Range please

Keep cardamoms out of Knuckles, is the fervent plea not only of a researcher but also of an erstwhile small-time cultivator of this

The Knuckles Range

spice.

“Disregard the clamour to re-introduce cardamom cultivations within the World Heritage Site of the Knuckles Range forests, for the devastation would far outweigh the benefits,” stresses researcher Pradeep Samarawickrama, who has spent many a long night and day in the area.

Pointing out that the main cardamom-growing areas are the districts of Matale, Kandy, Ratnapura, Kegalle and Nuwara Eliya, researcher Pradeep Samarawickrama explains that the answer would be to increase production in those areas without making inroads into the World Heritage Site with cardamom cultivations because the results would be disastrous.

Landslide triggered after cardamom cultivations at Dothalugala

The banning of cardamom cultivations in the Knuckles forests in 2010 has impacted only on the two districts of Matale and Kandy and that too only in some areas of these districts, he explains.

Researcher Pradeep Samarawickrama

Waxing eloquent on the beauty of Knuckles spreading over 21,000 hectares, where he has been conducting research in the past 15 years, Mr. Samarawickrama says that these montane and sub-montane forests are home to pygmy forests which are unique here. To survive against the gusty winds which lash this mountain range for six months, the pygmy forests which cling to the peaks have plants which grow only to a height of about a metre in very shallow soil. There are 35 isolated peaks at Knuckles which tower 900 metres above sea level.

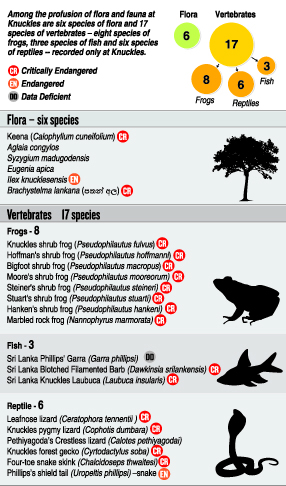

Many are the species, of both fauna and flora, endemic only to Knuckles (see graphic) and currently Mr. Samarawickrama along with another zoologist is studying one such, the information of which they are hoping to release at the end of the year. Of the 33 species of birds endemic to Sri Lanka, 30 can be seen at Knuckles.

Cardamom cultivations in a eucalyptus plantation at Thangappuwa in the proposed buffer zone at Knuckles. Pictures courtesy Pradeep Samarawickrama

Referring to the devastation that would be caused by the cultivation of cardamom (also known as henasaal and karadamungu) in this World Heritage Site declared by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) in 2010, he picks on the clearing of the forest as one of the major culprits.

“While cardamom cultivations are carried out at an elevation of 600 metres above sea level, usually the large trees are untouched because cardamom plants need about 60% shade. It is the under-storey or ground layer with valuable endemic plants including different types of ferns and orchids that fall victim to the clearing,” he says.

In the wake of the clearing for cardamom cultivations, there is massive erosion of land and Mr. Samarawickrama has seen and photographed the landslides which follow. These areas include Alugallena, close to the Knuckles Peak, Kalupahana, Dothalugala Man and Biosphere Reserve, Gammaduwa, Yakunge-hela and Thunhisgala Peak.

Mistflower, an invasive plant which is spreading in a cardamom plantation

Such forest clearing also brings about silt depositions in the streams flowing in those areas, causing harm and death to aquatic eco-systems, the Sunday Times learns.

The issues do not end there and Mr. Samarawickrama brings to the fore the serious phenomenon of ‘forest dieback’ at Knuckles which Horton Plains and the Peak Wilderness have been experiencing for some time. This is due to cardamom

Former cardamom cultivator Sandun Bandara

cultivations which cause the land to become bare, inviting invasive species such as Mistflower (Ageratina riparia).

The invasive species, in turn, will kill the native orchids, ferns and herbs, he says, lamenting that he has not seen ground orchids on cardamom lands during his forays into Knuckles.

Arguing that if cardamom cultivations are allowed within Knuckles, they would also be prone to diseases, he questions what the answer would be.

While some of the pests include shoot & capsule borers, thrips, hairy caterpillars, aphids, cardamom borers and cardamom mites, the diseases that could affect cardamom cultivations are clump, leaf blight, leaf spot and leaf rust. Aphids, mites and thrips cause the most harm to these crops. To control them, agrochemicals would have to be sprayed, and this in turn would cause a severe adverse impact on the plants and creatures in this high-endemic forest, adds Mr. Samarawickrama.

“Don’t allow cardamom cultivations within Knuckles,” is also the plea of Sandun Bandara from Meemure whose family had been part of the small cultivators of this spice since the 1970s. When Sandun joined them in the cultivations, his family had about 30 acres under cardamom and he is certain that his father would have had a permit for them.

Those were the days when impoverished and remote Meemure had about 100 families and those who cultivated cardamom would sell their yield to a benevolent mudalali who came to the village, he says, recalling how the mudalali helped the village.

“We had straw-thatched (piduru/illuk) homes and he brought thahadu for us, with a simple barter system being in operation,” says Sandun.

Things have changed drastically now, according to him, and bigger forces seem to be in control, with the “smallholder” not cultivating cardamom any more, in keeping with the ban.

The cultivations of these large holdings spread across a huge area, says Sandun, adding that forest clearing would leave behind only the roossa (giant) trees. All plants as “fat as an arm” would be the fuel, feeding the poranu which roast the pods.

While urging the authorities not to allow cardamom cultivations by big or small people within the Knuckles forest area, he says that as the big ones took control many of the humble villagers not only had to give up their lands but were also compelled to work as labourers in those holdings out of necessity.

Both the researcher and the one-time cardamom cultivator hail the Forest Department’s measures to stop this spice from being grown within Knuckles.

| Alternative crops for villagersNot only is researcher Pradeep Samarawickrama decrying the cultivation of cardamoms at Knuckles but also giving solutions on how to provide a livelihood to the villagers who have been engaged in producing this spice.Picking out the villages engaging in cardamom cultivation as Narangamuwa, Pallegama, Ranamure, Attanwala, Pitawalagama and Rambukoluwa in the Matale district and Meemure, Kaikawala, Thangappuwa, Rangala, Bambarella, Kabaragala, Lebanon, Hunnasgiriya and Hunnasgiriya Falls area in the Kandy district, he says that the people in these villages should be provided an alternative livelihood.

This could be the cultivation of pepper, ginger and thibbatu — which would not be vulnerable to animal foraging — for those living on the border of Knuckles in the Matale district. The community in the Kandy district could be mobilised to develop the buffer zone around the World Heritage Site by allowing them to grow fruit trees and other plants found in a typical Kandyan home-garden as well as cardamom, he points out, adding that both the Forest and Agriculture Departments should be involved in this process. Another answer would be for the Forest Department to take over the abandoned tea lands falling under the Land Reform Commission and lease them to the villagers in the Matale district to grow trees such as teak with a timber value. While stressing that he is not promoting eucalyptus and pinus, Mr. Samarawickrama adds that in the existing plantations in the Kandy district, villagers should be allowed to carry out cardamom cultivations as it is an ideal setting for this crop. |