Naming the Teardrop

In 1972, Ceylon became known as Sri Lanka – “Resplendent Land” in Sanskrit. In so doing, it reverted to its most ancient name, coupled with the honorific prefix, Sri. This occurred when the country became a republic and Queen Elizabeth II ceased to be head of state. During the four decades since, Sri Lankans (who had to divest themselves of the tag Ceylonese overnight) have grown accustomed to the contradiction of pottering down to the Bank of Ceylon to carry out financial transactions, and having their power provided (and often restricted) by the Ceylon Electricity Board. But in 2011 the government decided to eradicate the use of its colonial-tainted name from all state institutions. However the brand name Ceylon Tea remained, as it is recognised internationally, and any tinkering might well be commercially negative.

This is a token exercise, for unless legislation is introduced to curb the use of Ceylon in non-governmental circumstances, the name will remain abundantly apparent. The list of companies and organisations that incorporate it is lengthy – from Ceylon Oxygen, Ceylon Weighing Machines, Ceylon Leather Products, Ceylon Theatres, Ceylon Business Appliances, and the newspaper Ceylon Today, to Ceylon Rugby, Ceylon Moor Ladies’ Union, Ceylon Bible Society, and the Ceylon Railway Uniform Staff Benevolent Fund.

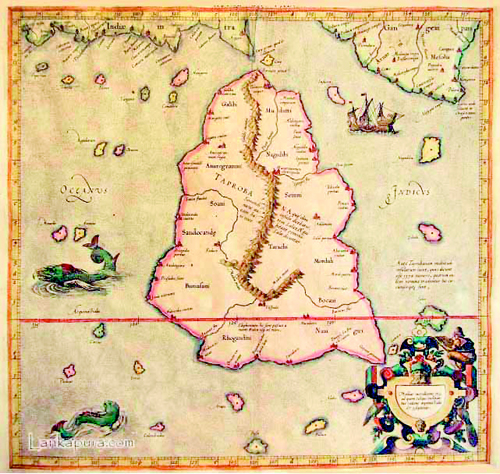

Claudius Ptolemy’s 1st century map of Taprobane (Sri Lanka) (Claudius Ptolemy /PD/Wikicommons)

After the British acquired the Dutch colony of “Zeilan” in 1796, the anglicised version of the name was adopted. English-language novelists began using the island as an exotic location, and often included Ceylon in their titles: William Dalton’s Lost in Ceylon (1861), Bella Woolf’s The Twins in Ceylon (1909) and More about the Twins in Ceylon (1911), FA Symons’s Cecily in Ceylon (1914), Isabel Smith’s A Marriage in Ceylon (1925), Maurice LW Wiltshire’s Billy in Ceylon (1929), Harry William’s The Twins of Ceylon (1957), Edward S Aron’s Assignment Ceylon (1973) and Edie Meidav’s The Far Field: A novel of Ceylon (2001).

Moreover, there are the early English descriptions of Ceylon, starting with Robert Knox’s classic, An Historical Relation of Ceylon (1681), based on his twenty-year captivity in the mountainous Kandyan kingdom. (This perennial bestseller was the first book to bring the name Ceylon to the attention of the British public.) The rest are by nineteenth-century colonists and visitors – for example, Robert Percival’s An Account of the Island of Ceylon (1803), James Cordiner’s A Description of Ceylon (1807), John Davy’s An Account of the Interior of Ceylon (1821), Major Forbes’ Eleven Years in Ceylon (1840), De Butts’s Rambles in Ceylon (1841), James Selkirk’s Recollections of Ceylon (1844), Henry Marshall’s Ceylon, A General Description of the Island and its Inhabitants (1846), Henry Charles Sirr’s Ceylon and the Cinghalese (1850), Sir Samuel Baker’s The Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon (1854), Sir James Emerson Tennent’s Ceylon (1859), Ernst Haeckel’s A Visit to Ceylon (1883), Thomas Skinner’s Fifty Years in Ceylon (1891), Alan Walter’s Palms and Pearls, Or Scenes in Ceylon (1892) and Constance Frederica Gordon-Cumming’s Two Happy Years in Ceylon (1892).

Which name to use for the island has been a problem down the ages, for Sri Lanka has had an extraordinary array attached to it by other cultures – probably more than any other South Asian country. Names such as Taprobane, Serendib and Ceylon are familiar, but Tenarisin, Tragan and Topazius are not. The oldest name for the island, found in the literature of both Buddhism and Brahminism, is the Sanskrit Lanka and its variations, such as Maha Lanka, the resurrected Sri Lanka, Sri Lake, Sakelan, Lanka-Puri (the Malay name), Maha Indra Dipa, Lince, Lans and Lana. Lanka became familiar throughout India because it was one of the principal locations of the epic poem, Ramayana, which also uses the name Lankadvipa.

In Buddhist literature, Sri Lanka was also known as Ratnadipa, “Island of Gems”, a reference to the variety of precious stones found most especially around Ratnapura (City of Gems). Another ancient name was Nagadipa, “Island of Snakes”, an allusion to the snake worship practised by an aboriginal tribe known as the Naga, which, it is believed, lived between the sixth century BCE and third century CE in the western and northern parts of the island.

After the arrival of Vijaya the island acquired the name Tambapanni (Tâmraparnî) which means “copper-palmed” in Pali. This curious appellation is explained in the Mahawamsa, written in the sixth century CE. The monk who compiled it relates that Vijaya’s followers arrived by sea, exhausted by sickness and so weak that they had to crawl ashore on their hands and knees. Later, they noticed the soil left clinging to their palms was a strange copper colour. Others think the name comes from the Sanskrit tambrapani, which means “the great pond” or “the pond covered with red lotuses”, probably referring to the large irrigation tanks for which the island became renowned in ancient times.

Taprobane – pronounced Tap-ROB-a-nê – the name by which the island was first known to the Greeks, is thought to be a corruption of Tambapanni. However, some believe it is derived from tapu-ravan or “the isle of Ravan” (a reference to the king of Lanka, Ravana, the villain of the Ramayana); others that it comes from the Hebrew taph-porvan or “golden coast”, which, like Tambapanni, is another allusion to the characteristic colour of the island’s soil.

The name Taprobane and the island’s location were unknown in Europe before Alexander the Great invaded India in 327 BCE. Subsequently Taprobane – about which improbable reports were brought to Europe – became the “land of the Antichthones”, the beginning of the antipodal world opposite northern civilisation. (In the Classical and Mediaeval European periods, when the northern hemisphere was known to geographers but its southern counterpart – the Antipodes – remained a mystery, the unfamiliar inhabitants were termed “Antichthones”.) Pliny the Elder remarks in The Historie of the World (1601): “Many have taken it [Taprobane] to be the place of the Antipodes, calling it the Antichthones world.”

One of the improbable reports regarding Taprobane was by the unknown (and plagiaristic) author of The Voiage and Travaile of Sir John Maundeville, Knight (1357). Mandeville, as his name is usually rendered, claims to have been at the court of Prester John, the legendary Christian patriarch and king said to rule a nation lost amidst the Muslims and pagans in the Orient, a tale that gripped the imagination of Europe from the twelfth to seventeenth centuries:

“Toward the east part of Prester John’s land is an isle good and great, which men call Taprobane, which is full noble and full fructuous. And the king thereof is full rich and under the obeisance of Prester John. In that isle be two summers and two winters and men harvest the corn twice a year [at least this seasonal aspect is correct].

“In this isle of Taprobane be great hills of gold, that pismires [synonym for ants: piss+mire refers to the urinous smell of anthills] keep full diligently. And they fine the pure gold, and cast away the un-pure. These pismires be as great as hounds, so that no man may dare come to these hills for the pismires would assail them and devour them. No man may get of that gold, but by great sleight.

This “great sleight” is achieved during the heat of the day when the ants retreat into the earth, leaving the gold unattended. Then “the folk of the country take camels, dromedaries, and horses”, proceed to the ant territory and quickly load the animals with as much gold as possible before the giant insects return to the surface.

During the cool season mares with young foals were fitted with low-slung sacks and sent forth among the ants, as “they let nothing be empty among them”. When the inhabitants see the sacks are full they bring the foals into view so that the mares return to their offspring.

Another allusion to Prester John’s fabulous kingdom is by Friar Giovanni de’ Marignolli. “From Paradise to Taprobane is forty leagues, there may be heard the sound of the Fountains of Paradise” (1335), is often used to bolster the travel industry’s concept that Sri Lanka is Paradise without thought: hearing the sound of the paradisiacal fountains is not ‘being there’.

Miguel de Cervantes creates a fanciful Taprobana in Don Quixote (two volumes, 1605 & 1615): “What shall we do,” replied Don Quixote, “but assist the weaker and injured side? For know, Sancho, that the army which now moves towards us is commanded by the great Alifanfaron, emperor of the vast island of Taprobana; the other that advances behind us is his enemy, the king of the Garamantians, Pentapolin with the naked arm, so called because he always enters into battle with his right arm bare.”

In addition, John Milton refers to Taprobane in Paradise Lost (1667), “And utmost Indian Isle Taprobane”, also in Paradise Regained (1671): “From India and the Golden Chersoness and utmost Indian isle Taprobane”.

In his talk titled “The Western Discovery and Mapping of Taprobane (Sri Lanka)”, delivered at the Sri Lanka Foundation Institute on February 18, 2000, Ananda Abeydeera commented: “Determining its size, shape, and exact position was a vexed question from the earliest ages of classical geography and there has long been speculation among the ancient Greeks and the Romans as to whether Taprobane was a second world or whether it was a very great island.”

Claudius Ptolemy (ca. 90-170CE), a Greco-Roman citizen of Egypt, was the most advanced geographer of his era and invented latitude and longitude. He depicted Taprobane “as an Indian ocean island of nearly continental size giving it fifteen degrees breadth and located it athwart the equator in the final regional map of his Geography”. Why Ptolemy’s Taprobane dramatically exceeded the island’s actual size is uncertain. Perhaps, Abeydeera suggests, it was due to the different meanings of the word dvipa commonly found in Indian texts – “island”, “island continent”, and “continent” – which might have led to an assumption by him that the southern Indian region, the Deccan Plateau, was a great island. Ptolemy’s world map from Geography suggests this might be the case: India is truncated and Taprobane appears to be the missing peninsula.

Nevertheless, Ptolemy seems to have integrated the main aspects of the island, because, as Tennent (1859) noted: “From his position in Alexandria and his opportunities of intercourse with mariners returning from their distant voyages, he enjoyed unusual facilities for ascertaining facts and distances, and in proof of his singular diligence he was enabled to lay down in his map of Ceylon the position of eight promontories upon its coast, the mouths of five principal rivers, four bays, and harbours; and in the interior he had ascertained that there were thirteen provincial divisions, and nineteen towns, besides two emporiums on the coast; five great estuaries which he terms lakes, two bays, and two chains of mountains.”

Cartographers have gone one step further than Tennent to identify the places indicated on Ptolemy’s map of Taprobane. Apparently there are Persian names such as Phasis fluvius for the Mahaweli (river) region where Persians lived, and Cando Canda Civitas for Chilaw (more precisely the area north of Kelani to the Deduru Oya). Sri Pada is called Maloea – the name by which the hills that surround it are termed in the Mahawamsa. Anurogammi almost certainly refers to Anuradhapura, Rhoghandini to Ruhunu, a southern kingdom founded ca. 200 BCE, and Nagadibi, the northern stronghold of the Naga tribe, Nagadipa. All these places are correctly situated.

Unfortunately Ptolemy’s Geography was lost for twelve centuries. Then, in the early fifteenth century, it was rediscovered, translated into Latin, and became available to European scholars through a number of editions. Thus the name Taprobane resurfaced, but after more than a millennia other names had been attached to the island, the most current being Seylan. Therefore travellers and geographers influenced by Ptolemy began searching for another island, the ‘real’ Taprobanes.

During the fifteenth century the Italian traveller Nicolo di Conti claimed it was Sumatra. As a result, considerable confusion arose. Cartographers such as Sebastian Munster called Sumatra Taprobane on his world map of 1550. To add to the “geographical vicissitudes of Taprobane”, German philosopher Immanuel Kant maintained the island was Madagascar. This is of passing interest because during early geologic time, when the ‘supercontinent’ Pangaea incorporated most of the Earth’s landmasses, Madagascar, India, and Sri Lanka were lumped together as part of Africa before plate tectonics forced the latter two northwards.

Christopher Columbus, who had a muddled concept of geography, thought he had reached Taprobane in 1492 when in fact it was what would be called Hispaniola (the island now divided between Haiti and the Dominican Republic). “Castilian prelate and overzealous friar Jiménez de Cisneros disparaged Columbus’ pretensions that he had been to Taprobane but asserted that he himself would embark upon a voyage in search of the ‘true Taprobana’ if their majesties would favour him with their permission and provide him with a formidable fleet.”

Abeydeera concludes: “The Taprobane story, with its broiling controversies and conflicting interpretations sheds important light on the processes of discovery and on the transmission of geographical knowledge in classical times, in the Middle Ages, and in the era of the great discoveries. Taprobane, like El Dorado, Ultima Thule and Atlantis, was a touchstone for the geographical imagination.”

Unresolved though the issue remains, the name Taprobane is still associated with the island and, as with Ceylon, is used commercially – Taprobane Digital, Taprobane Trading Overseas, Taprobane Travels, Taprobana Lodge, etc.

Later, Ptolemy’s Taprobane became Simundu, Palai-simundi and Salike. Palai-simundu is perhaps derived from the Sanskrit pali-simanta, or “the head of the sacred law”, as the island had become a major centre of Buddhism. Salike may well have been a seaman’s corruption of Sinhala, Sihala or Sihala-dipa, the name chosen by the Sinhalese themselves, which means “the dwelling place of lions”; although some assert that “the blood of the lion” is more correct.

Sinhala refers to the legendary founder of the Sinhalese race, Vijaya, whose grandmother fulfilled a prophecy that she would consummate a “union with the king of beasts” – a lion. She gave birth to twins – Sihabahu, or “lion-armed”, Vijaya’s father – and Sihasivali, a girl. The exotic family lived in a cave, the entrance to which was blocked by the lion. Eventually, Suppadevi (the mother) and Sihasivali managed to escape and Sihabahu killed his father, after which he married his sister, established a kingdom, and sired many children, the eldest being Vijaya.

Sri Lanka’s Tamils, who do not subscribe to this creation myth, refer to the island as Ilankai, derived from Lanka.

Sinhala, along with the suffix –diva, dwipa or dweepa (“island”), was subsequently converted into Silan-diva and Seren-diva, from which is derived Serendib or Sarandib, and, in Persian, Serendip. Arabs, especially mariners, also called the island Jazirat Kakut, “island of gems”, while the Moors called her Tenarisin, “island of delights”.

Serendib is another well-recognised former name also used commercially – Serendib Cooker Shop, Serendib Bookshop, Serendib Flour Mills, Serendib Mini Cabs and even Serendib Flys (presumably suppliers of fish-bait). The use of the name in two extraordinary books has been instrumental in the increase of international familiarity with the name. The Arabian Nights relates the “Seven Wonderful Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor”, the sixth and seventh of which were to Serendib. In fact, it appears the Sindbad saga was not one of the book’s original stories, but was introduced by the orientalist and archaeologist Antoine Galland in his French translation (1704-17). However, Sindbad reached a much wider readership in 1885 following Richard Burton’s English translation.

The Three Princes of Serendip is a collection of tales originally published (and probably compiled if not written) by the Venetian printer Michele Tramezzino in 1557. This is the first instance of the island, occurring in the title of a work of fiction, although much of the story takes place in neighbouring lands. It was an episode in the book concerning a camel that inspired Horace Walpole to coin the now clichéd word serendipity, which has nevertheless perpetuated the awareness of Serendib as a former name of the island.

Down the centuries and across cultures, Serendib was transformed into Sielediba, Serindives, Selin, Seilan, Syllen, Sillan, Celan, the Portuguese Ceilão, Spanish Ceilán, French Selon, the Dutch Zeilan (as well as Ceilan and Seylon). Finally it became Ceylon, and the variants Seylan (Sri Lanka has a bank bearing this name), Zeylan and Ceylan. Although the Portuguese used Ceilão, the names Tragan, Trante, and Caphane also appear on Portuguese maps. Other names to be found on mediaeval maps are Siledpa-camar, Lanka Camar, Pertina and Tuphana. The last is derived from the earlier-mentioned Topazius, a name given by the Greek writer Polyhistor during the first century BCE because the island produced a liberal quantity of fine topaz.

During recent decades certain focus has been placed on the other part of the modern name, with suggestions that Sri should be changed to Shri, to more accurately represent the sound of the word, thus giving the name more numerological potency. Indeed this modification did take place during the presidency of Ranasinghe Premadasa (1989-1993) in certain official matters, such as with postage stamps. However, in general Sri Lanka remains, just as the former names Ceylon, Serendib and Taprobane linger within the teardrop island.