News

Accidents, derailments don’t deter train travellers

Around 6 p.m. on a working day evening, a tsunami of commuters overwhelmed the Colmbo Fort Railway Station. The women run towards the platform where the Colombo Fort-Polgahawela train was waiting; their hairdos askew, holding up their saris, pushing agaist each other trying to get on board. The men sprint towards the train, their leather brief cases flying besides them. Some manage to get on board; others hang on to the footboard, stand between carriages or get on to the roof. The train takes off after a while, packed with human bodies.

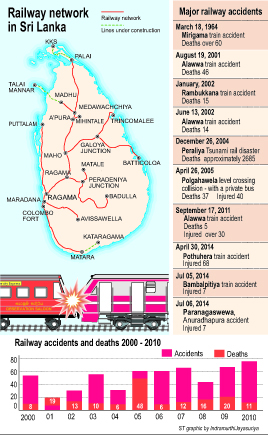

The railway service has been in the news recently over a number of derailments, accidents and commuter deaths. In the first weekend of this month, an express train from Colombo to Matara derailed near Bambalapitiya, injuring eight and causing delays along the Coast Line. A day later, a Colombo – Pallai train derailed near Anuradhapura causing delays along the Northern Line. A couple of weeks ago, a 20-year-old died from severe head and limb injuries caused by falling off the footboard of a moving train. On the same day, a 25-year-old died when a train accidentally took off right over her legs.

On one occasion, we were waiting for a morning train, and when it finally arrived at the platform, one carriage was drippng blood, one daily commuter waiting at the Colombo Fort station recalled. “There was blood coming down the roof of a carriage, like red ribbons. Someone travelling on the roof had smashed his head against an object overhead.”

The horrifying accidents or derailments do not faze the daily commuters from packing every available nook and corner of rush hour trains. Menaka, who takes the Main Line train daily to commute to her workplace in Colombo from Ragama, when asked whether she is bothered by news stories of derailments and accidents, just shrugged and replied, “What to do? It’s the best option for me.”

The horrifying accidents or derailments do not faze the daily commuters from packing every available nook and corner of rush hour trains. Menaka, who takes the Main Line train daily to commute to her workplace in Colombo from Ragama, when asked whether she is bothered by news stories of derailments and accidents, just shrugged and replied, “What to do? It’s the best option for me.”

“It’s cheap and affordable compared to buses, and you can avoid the horrendous rush hour traffic on Baseline Road or Galle Road,” she said. “And the environment is cleaner too; you don’t have to travel in dust and exhaust fumes.”

Menaka still had plenty to complain about: her trains from Ragama are never on time because almost every day there’s a delay caused by a signal failure, plus the trains are overcrowded and sometimes commuters have to wait a long time to buy tickets during peak hours.

“They put express trains behind slow trains,” she added. “The slow trains stop everywhere so because of that the express train is also delayed.”

Sivaraj, who commutes between Jaffna and Colombo on weekends, described the rail service as the “worst service in the country.”

“The Yal Devi train is decades old and taking it is a nightmare,” he said. “And this is the most profitable railway line in the country. Why haven’t the authorities been able to upgrade this service?”

Railways Department General Manager B.A.P Ariyarathna defended the service saying “wide publicity” for derailments or accidents lets the “public think this is happening all the time, when in fact it’s not.”

“When you consider the records of the past couple of years, the number of derailments is down,” he said.

There are a number of reasons a train could derail, Railways Department Operations Superintendent L.A.R. Ratnayaka said. There could be issues with the rail tracks themselves, such as erosion, overuse or for coastal rail tracks, frequent corrosion. Excessive heat could also alter the tracks. Sometimes deliberate sabotage could play a part. Engine issues or driver’s faults could also factor in, Mr. Rathnayaka said. Each case is investigated by a minor or a major board appointed by the Department.

To minimise derailments and to ensure that rail tracks are always kept in good condition, they are replaced every six to seven years. Coastal tracks are replaced every four to five years. The Department also imposes speed limits on tracks that look bad. “One problem is that drivers don’t adhere to speed limits,” former Railways General Manager Priyal de Silva said. “So the supervising officers should make sure that drivers stick to speed limits.”

“Back in my day, we had a scheme to increase the economic life of rail tracks,” he added. “We’d replace rail tracks from places like Anuradhapura and Puttalam with new ones, and take those used tracks and replace coastal tracks that are extremely prone to corrosion with those. So the residual life of the tracks together would be increased by about 13 years. Now they keep replacing coastal tracks with new ones, which is more expensive.”

The need for infrastructure improvement is one of the biggest issues facing the troubled railway service, which significantly contributes to overcrowding, delays and accidents.

“Railway infrastructure needs to be modernised,” P. Sampath Rajitha, secretary of the Railway United Front, said. “After an incident, the officials do these reports, which no one else except the senior officials are allowed to see, and they might suspend some workers, but after that, nothing.” They talk of modernising, but don’t follow up, though we keep insisting the, he said.

For example, about 60 percent of the rail network in the country still uses the signaling system installed by the British in the 1860s. The system was upgraded some years ago for busy rail tracks around Colombo. However, a senior railway official on condition of anonymity said, whatever improvements need to be made, “must be done considering the condition of the country.”

“In the 1960s, the Government centralised traffic in and around Colombo with our own money,” the official said. “Today we cannot install a signaling system for a single station without a loan. So how can we do this for 40 or 50 stations? The old system needs to be improved, but we have to consider the necessity and the economy. For outstations where some 30 or less trains run on a single day, there’s no need to upgrade the signaling system.”

The railway system is inefficient because it runs on a paper-based system with little to no integration, says Railways technical officer Anura Pushpakumara Kasthuri, who is currently working on implementing an optimisation and integration system he has developed for the Colombo-Matara track, which is expected to mitigate train delays.

“They have agencies, but just because they exist doesn’t mean they run properly,” he said. “The old system cannot cater to modern passenger needs. It needs a rigid, new system, like the optimisation module we are working on now. But for these things to work, the authorities need to be willing to support and allocate necessary resources.”

Then again, the railway service has been running at a loss for several years, and is heavily subsidised by the Treasury, according to Central Bank figures.

“Thing is, for the railway to maintain tracks, buildings, signals and whatnot, it’s not possible to recover that cost from ticket fares alone,” Mr. Ariyarathna said. “We provide a service. We give lot of concessions to Government servants and schoolchildren. If we were to become purely a commercial service, the major part of the financial loss can be covered but those concessions would have to be discontinued. If that happens, train fares would be on par with bus fares. Our fares are below bus fares. So part of the burden would be on the public.”