News

Young Lankan scientist makes life-saving snakebite discovery

A landmark discovery by a Sri Lankan scientist could save thousands of lives lost through snakebite the world over.

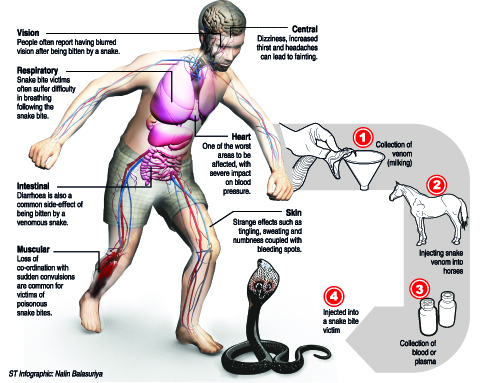

A snakebite victim’s life often hangs in the balance in the minutes during which doctors watch for symptoms of poisoning before  injecting the person with anti-venom as the remedy itself could cause severe allergic reactions that can cause immediate death.

injecting the person with anti-venom as the remedy itself could cause severe allergic reactions that can cause immediate death.

Not every snakebite sends poison into the bloodstream: sometimes the fang fails to inject the venom; sometimes the snake had engaged in a recent attack that depleted its venom sacs and the new bite fails to carry enough venom to harm the victim.

Unfortunately, the wait of a few minutes to ascertain such information could mean life or death.

It could also cause permanent damage to organs or nerves as once signs of paralysis and muscle damage begin to appear they cannot be reversed by antivenin.

The good news is that scientists have found a blood test that could be successful in detecting whether venom entered into the bloodstream even before symptoms appear.

This breakthrough was made by Dr. Kalana Maduwage of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Peradeniya, who is currently doing his PhD at Newcastle University, Australia, in snake venom science.

He and a team of researchers tested a common enzyme in snake venom called Phospholipase A2 (PLA2). They had collected blood samples from those who had symptoms of snakebite and measured these against blood from people who were not bitten.

This particular enzyme was found in high levels in snakebite victims who had the venom penetrate their blood stream.

Dr. Maduwage says that both Sri Lankan and Australian victims of snakebites were tested for this new method. Bites of four venomous Sri Lankan snakes – cobra, krait, Russell’s viper and hump-nosed viper – were tested successfully.

Sri Lanka records one of the highest levels of snakebite in the world. According to the Health Ministry nearly 39,000 snakebites are reported to government hospitals every year, ending in approximately 100-150 hospital deaths.

Dr. Maduwage paid special tribute to the supervisors of his study, Professor Geoff Isbister and Dr Margaret O’Leary at the University of Newcastle. Dr Isbister is a world expert on snakebite research and has published more than 250 scientific papers on snakebites and spider bites. Dr. Maduwage said he was lucky to have Professor Isbister as his supervisor.

The work, previously published in Nature Scientific Reports, was presented last month at the Australian Society for Medical Research Annual Scientific Meeting in Sydney.

Dr. Maduwage is working hard with the team to develop this concept into a bedside test kit that can be easily available around the world.

Dr. Maduwage has more than 10 years’ experience in the study of snakes, especially the hump-nosed pit viper.

In addition, he has also discovered and scientifically described 10 varieties of fish, three new snake species and one lizard species.

Dr. Maduwage, who is still in Australia doing his PhD applauds the research-friendly environment in Australia but says he will return to Sri Lanka to serve his country upon completion of his PhD and will keep on developing techniques that can save more lives.

| How anti-venom is produced

A simplified explanation of how snake antivenin is produced is that extremely small amounts of snake venom are injected into mostly horses on a regular basis over a long period of time. |