The numbers didn’t add up but sketches did

Barbara Sansoni was 11 years old when she met Maria Montessori. Having fled to India after being exiled by Mussolini during WWII, Maria’s school in the Olcott Garden Bungalow already had a small complement of students. Now, here was this child in need of her guidance. Barbara, enrolled close by in a boarding school in Kodaikanal, was a poor student. A bad case of dyslexia had left her struggling to read and write and as she told Maria plaintively – “the worst one is sums. I can’t add or subtract.”

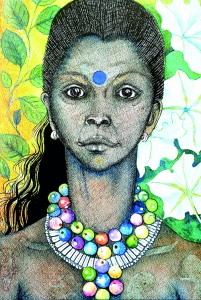

Fully occupied: Barbara at home with her books, crossword and creations. Pic by Susantha Liyanawatte

Over the course of their conversation, Maria discovered that Barbara loved to draw and her advice was that she draw as much as she could – history would be figures of people, maths little groups of pebbles that she could add to or subtract from. This made sense to Barbara, whose letters home were already filled with sketches of cartoon figures, each more expressive to her than any sentence she could have constructed. “Still, it wasn’t as easy as that, but she was a wonderful woman,” says Barbara, remembering.

She and her second husband, the architect and scholar Ronald Lewcock are just finishing their lunch when we arrive. Barbara, dressed in a skirt of many colours, with a shirt to match and an assortment of colourful, beaded chains around her neck looks like an ambassador for Barefoot. She is nestled among some of her most recognizable creations – there are the brilliantly coloured cushions at her back, the ‘wall furniture’ or hangings with many pockets on the wall beside her and dangling from a chair nearby are the bags that are so recognizably from the store she founded. She has a pair of bad hips and finds walking difficult, so it is Ronald who goes looking for a copy of ‘A Passion for Faces’ and who identifies the oldest dated picture in the set – a line drawing of Barbara’s sister Mary, from 1964, when Barbara was 35 and Mary 25.

Just launched, the book juxtaposes simple sketches, vividly coloured paintings and the odd, fantastical portrait that take for their theme the faces of people Barbara has encountered in the course of her long life. In each, she explores her fascination with our genetic heritage – in the line of the cheekbones, the flaring of a nostril, the curl of a hair, the fullness of a lip. In fact, if she’d had her way, the book would have been called ‘Races in the Face.’She is regretful that she didn’t pay more attention to some when she was working on them; she never imagined they would be published. She blames her distraction on why she was in the vicinity of her subjects in the first place – the old houses she had come to sketch.

She would write in a poem titled Houses and Faces: ‘To me it isn’t important who lived in the house, history/doesn’t make ugly things beautiful – but age does/A face, after all, is a house, built centuries ago by genes.’ By the beginning of the 1960s, Barbara’s drawings of old buildings were already being published in the Ceylon Daily Mirror. She would go looking in villages and rural hamlets for architectural gems (and would often be asked by the villagers if she could sketch them too.) She did this,

A personal favourite: One of Barbara’s ‘races in the face’-sketches

she says, because she wanted to share her pleasure in the buildings but her sketches now serve too as memorials to structures long torn down and destroyed. It was these that first brought Ronald into her life – visiting the island to conduct research, he had been determined to meet the artist who had created these charming drawings and who simultaneously penned pragmatic articles on the use of perforated walls that ‘breathed.’

Married to Hildon Sansoni at the time, Barbara was already a mother (Dominic, her youngest child, was not yet six) and she was completely unaware that the decade ahead would transform her career and define her legacy as an artist and a designer.

When an Irish nun, Sister Good Counsel, Provincial of the Good Shepherd sisters of Southeast Asia, approached Barbara it was because she knew her as a family friend and an artist in her own right. Her wish was that Barbara could become involved in a programme that taught young girls how to weave. The girls in question had nowhere else to go – impoverished, some were orphaned, others child servants who had then been thrown out by the families they lived with. Barbara’s first response was to say no, because as she stated clearly, she had “no interest in good works.” Sister Good Counsel set up a meeting anyway, and that was that.

When Barbara became involved in the project, the women were only weaving towels and dish cloths with a simple stripe at one end. Barbara saw that if they were to make a profit from these and sell them abroad, she would have to bring an entirely new aesthetic to the design that would appeal to a much wider audience. “I was also a friend of the traditional weavers and I didn’t want to get my weavers to start copying their things,” she says.

Hildon and she decided they would establish and finance four village weaving centres. They were not easy to get to for Barbara, who then drove a small Volkswagen, but it seemed important to her to bring work to villages where it was scarce, and to avoid at all costs a factory-like set up. The girls would weave in large halls with open windows. Barbara’s contribution was her particular talent – an incredible eye for colour which she combined with a gift for innovation. When only white yarn was available, she would unwind spools of thick jute rope and weave it in to create texture. At other times she would have to find ways to work with a limited range of colours or poor quality thread (never afraid to complain, she brought her case directly to Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake himself and says he was very helpful in seeing the quality of the yarn improved.) She would eventually learn how to dye fabrics and trained a group of master dyers to create those spectacular hues.

Increasingly, Barbara saw they were doing good in the communities they worked with. She is echoing Maria Montessori’s opinion when she says: “when you meet children who have been uneducated you can’t go back, too many years have passed, a skill is the best education a brain can have.” Proficiency in weaving could still develop the whole person. They would simultaneously acquire a whole gamut of other abilities – from problem solving, to basic mathematics, manual dexterity and a discipline that would serve them well in all aspects of their lives.

When money became tight, Barbara took the extremely unconventional step of selling the girls’ products in her own home (her invitation to drinks read: ‘You will find various things, handwoven by poor girls around the place. Don’t let me feel ashamed that I have put them there.’) Her trusted butler Ekanayake would be standing at the ready to offer a price on the neat little parcels and would handle the money afterward – Barbara never having overcome her fear of doing math.

From that point on, the small business would only grow in renown. In 1970 a prestigious Rockefeller Scholarship would allow her to tour 14 countries and meet some of the world’s most emminent designers, but she really knew she had arrived when Geoffrey Bawa chose to use her fabrics in the Lighthouse Hotel. (They were friends, but she knew he would not have singled her out unless he genuinely admired her work.) Her design team also swelled to encompass the likes of Marie Gnanaraj and Preethi Hapuwatta, who she would collaborate with in years to come.

As they began to consider expanding their range, Barbara decided that any clothes they made would take the shape of the traditional garments worn by ordinary people about their work. There would be no fitted sleeves or bust darts (“bust darts are bad words at Barefoot”) and the colours would reflect the lushness of the tropics. She herself has worn these clothes throughout her life, even when accompanying Ronald to the UK and the US (they will celebrate their 34th anniversary this year). As you might expect, Barbara found herself coming in for criticism – society women compared her to their ayahs and once her bank manager cautioned her that her midriff-baring garments might “incite men” and place her person in jeopardy. Barbara’s response was to contemptuously ignore the former, the latter she reassured by showing him the heavy object she carried around in her bag to deter any assailants.

Her confidence and stubbornness sprang from how fully she embraced life. “I love life, I like laughing, I don’t take it seriously…those were the clothes I felt most comfortable in and they were lovely to look at,” she says.

As we talk, Ronald writes in a copy of ‘A Passion for Faces’ and hands it over for Barbara to sign. Her voice softens always when she speaks to him, he who probably knows her best and takes such pride in her accomplishments. There is much joking about how she wields her walking stick to bring him into line. As I am about to leave, having been pressed to accept a milk toffee, she pulls me back to tell me sotto-voce that she is most profoundly grateful for him. “Write that down,” she says, “and also that I wouldn’t have been able to do it without the stick!”