Following the monk method

View(s):“Bananas are very profound.

“They are so commonplace that we assume we know everything about them. In fact, we don’t even know the correct way to peel a banana. Most people peel the banana from the top, the end with the stalk. However, the experts on bananas, the monkeys, always peel their bananas from the opposite end. Try it and see. You will find it so much less troublesome following the monkey method.

“In much the same way, meditating Buddhist monks and nuns are experts on separating the mind from the difficulties that surround it. So I invite you to follow the monk method of dealing with life’s problems. Like peeling a banana, life will be much less troublesome.”

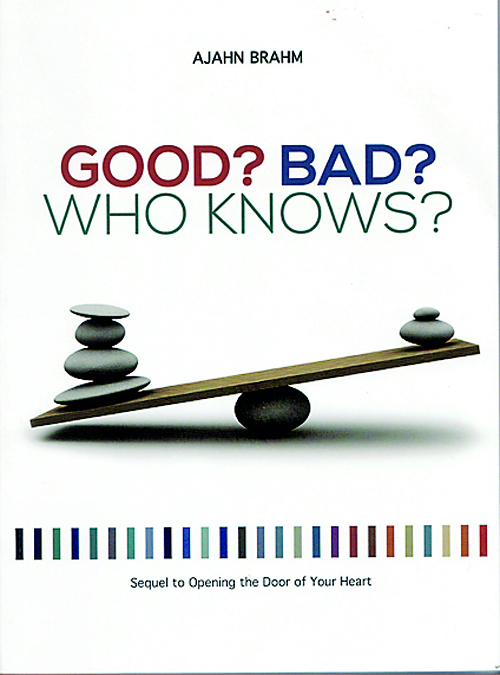

With these simple and inspiring words in his foreword, Ajahn Brahmavamso begins his new book ‘Good? Bad? Who Knows?’. It is a sequel to his best-seller, ‘Opening the Door to Your Heart’.

It is, in a way, a story book where Ajahn Brahm relates stories- 108 stories in total. Some are short, some are a little long. All are most interesting and most readable. This is his typical style. Even his Dhamma talks are full of stories and jokes. But within them, there is so much Dhamma which even non-Buddhists appreciate. They feel they are listening to an interesting talk but through them he gives a lesson which everyone can easily grasp.

The book highlights various aspects of the Buddha’s teaching. Ajahn Brahm has divided them into twelve categories. The categories are: Aspiration, Compassion, Contemplation, Cultivation, Equanimity, Forgiveness, Generosity, Kindfulness, Letting go, Loving Kindness, Non-Self and Wisdom. The reader thus knows exactly what each story is related to. In fact, Ajahn Brahm sums up the topic in the last para of each story.

To Ajahn Brahm there are no criminals. To illustrate ‘Compassion’, he relates this story: I received a phone call from a custodial officer at a local prison. He wanted to speak to me personally to invite me to come back to his prison to teach. I replied that I was very busy now with many more duties than those days when I used to visit his prison regularly. I promised that I would send another monk.

“No”, he replied. “We want you.”

“Why me,” I said.

“I have worked in the prison service most of my life,” explained the prison guard “and I have noticed something very unique with you. All the prisoners who attended your classes never returned to jail once they were released. Please come back.”

This is one of the most treasured compliments that I have received. So I thought about it afterwards. What had I done what others hadn’t that had genuinely reformed those in jail. I figured out that it was because, in all my years teaching in prions, I had never once seen a criminal.

It is irrational to define someone by one or two, or even several, horrific acts that they have done. It denies the existence of all the other deeds, their many noble acts that they have performed. I recognised the other deeds. I saw a person who had done a crime not a criminal. They were much, much more than the offence for which they were doing time.

When I saw the person and not the crime, they also saw the other part of themselves. They began to have self-respect, without denying the crime. Their self-respect grew. When they left jail, they left for good.

The five fingers

Here is a story where Ajahn Brahm talks about the five fingers to demonstrate ‘Cultivation’. The five fingers were having an argument over who was the most important finger.

“I am the most important,” said the thumb, ‘because I am the strongest. Also, when people approve of something they use me. I am the ‘O K finger!”

“No way,” said the index finger. “I am the most important. I am the finger of wisdom because I am used to point out things. Moreover, when people want to say ‘Number One’, they use me.

“Ridiculous!” sneered the middle finger. “I am the biggest finger and can therefore see further. I am so powerful that when people lift me up they get very upset. Moreover, the Buddha taught that the way to Enlightenment is the Middle Way and I am the Middle Finger.”

“I’m sorry but you are wrong,” said the fourth finger kindly. “I am the most important because I am the finger of love. When people fall in love and get engaged, they put the ring on me. When they commit to care for each other in marriage, again they place the ring on me. I am the finger of love, love is the most powerful force in the world and therefore I am the most important finger.”

“Excuse me,” interrupted the small finger. “I know I am not tall or strong and am often ignored, but I believe I am the most important finger. Although people use me to do dirty jobs, like removing wax from their ears, when they pray to the Buddha, I am closest to the Buddha! Raise your hands, pray and you will see.”

So, in any community, family or temple, the humble members who do the cleaning are the most important because, like the little finger, they are close to the Buddha.

Mother’s love

Ajahn Brahm illustrates ‘Kindness’ with an experience as a kid: My parents were poor…I spent a lot of my time playing soccer in the street with my friends. When I came off the worst side of a tackle, I would graze my knees on the stone pavement or hard bitumen. Bleeding and in pain, I would run to my mother in tears. She would simply kneel down and press her lips on the wound and ‘kiss it better’. The pain would always go away. Then after quickly putting on a bandage, I was back kicking that soccer ball almost immediately.

Many years later, I wonder how unhealthy it was to place a mouth full of germs on an open wound! But it never led to an infection. Moreover it was an instant pain killer.

I learnt the healing power of kindness from my mother, through incidents such as this.

These are just three stories randomly picked as examples of Ajahn Brahm’s cleverness in relating stories.And I deliberately picked the short ones to save space.

‘Good? Bad? Who Knows?’ is the ‘one-shot’ type of book which can be read from start to finish in one go. It’s so readable, easy in style and absorbing.

Book facts

‘Good? Bad? Who Knows?’ by Ajahn Brahmavamso. Reviewed by D. C. Ranatunga