News

How Kadirgamar made Lanka proud at UNHRC

Mr. KADIRGAMAR (Sri Lanka) said his country had good reason to be proud of its recent achievements in the field of human rights. The changes that had taken place over the previous six months were a triumph not only for all its citizens, but also for the lofty values and principles for which the Commission — and indeed the United Nations — had stood for half a century.

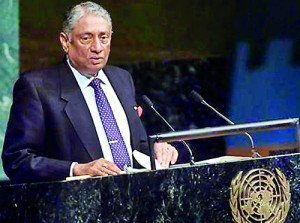

Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar presenting Lanka’s case at the UN General Assembly

The people of Sri Lanka had rejected in no uncertain terms a regime under which the rights of the individual had been violated with impunity. By electing the Peoples’ Alliance Government and Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga as President at the elections held in 1994, the people of Sri Lanka had given an incontrovertible mandate for the pursuit of peace and justice and the resolution of the conflict in the north and east of the country through political negotiations. It was also a mandate to protect and promote the human rights of a population whose rights were being violated by two groups of militants: one fighting for a separate State and the other attempting to overthrow an elected Government by force of arms, which had led to a strong reaction on the part of the law-enforcement agencies of the State.

The mandate had been a clear signal for a change involving the participation of the people in all important matters affecting its destiny. The Government remained accountable to its own people and committed to the principles enshrined in the international instruments to which Sri Lanka was a party. It would measure scrupulously its progress against those yardsticks of responsibility, accountability and commitment as a constant reminder against the perpetration of excesses.

Sri Lanka had long been known as a beautiful and serene island. Of late, however, that idyllic land and its people had been stricken by unspeakable tragedies. The insurgency by the two militant groups and the reactions they had provoked had imposed severe strains on Sri Lanka’s long-cherished democratic traditions. Opportunities to transform the island into a prosperous country had been lost.

Within two weeks of assuming office, however, his Government had taken the bold step of initiating a dialogue with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), with a view to resolving the conflict that had plagued the country for over 10 years. The ban on the transport of certain items to the Northern Province had been lifted by the Government without any preconditions, in line with its commitment to alleviating the sufferings of innocent civilians in the Province who had been caught up in a conflict over which they had little or no control. Those positive steps had culminated in an agreement on a cessation of hostilities effective 8 January 1995 which had been warmly welcomed by Sri Lankans and the international community alike.

During his recent visit to the United States of America, he had been encouraged by the support given to the process by the Secretary-General of the United Nations and the Government of the United States. He had been particularly heartened by the statement made by the Assistant Secretary of State for South Asian Affairs to the House International Relations Committee on Asia and the Pacific. She had stated that her Government strongly supported the ongoing peace talks, adding that the Sri Lankan Government had shown courage and vision in its moves to reopen a dialogue with the LTTE in the north. Obtaining a lasting peace would be a long, arduous struggle, she had said, but she was convinced that the Sri Lankan Government was committed to the process and was acting in a spirit of openness and good faith. She had urged the LTTE likewise to act in a manner that would further the prospects for a lasting and comprehensive peace.

She had also paid tribute to the dramatic progress made in protecting human rights in Sri Lanka. Emergency regulations had been allowed to lapse in all but war-affected areas and the remaining emergency regulations had been modified in accordance with United Nations Commission on Human Rights recommendations. Disappearances had virtually ceased in Government-controlled areas in 1994; and the Government had created three regional commissions to investigate disappearances.

It was certainly the desire of the President of his country to negotiate a permanent cease-fire and reach a political settlement designed to achieve peace with justice and dignity for all. His Government’s transparency was amply demonstrated by its invitation to the representatives of the Governments of Canada, the Netherlands and Norway to head the committees appointed to oversee the cessation of hostilities.

Among the numerous lessons learned from the prevailing ethnic conflict was the ease with which destruction could be caused and the difficulties involved in reconstruction. With a view to rebuilding the damaged economy of the Northern Province and reconstructing its infrastructure, the Government had pledged nearly 40 billion Sri Lanka rupees (US$ 800 million). Given the country’s resource constraints, that was an enormous amount of money. He therefore warmly welcomed the offer of the European Union to collaborate with all partners in the economic reconstruction of the areas affected by the conflict.

The peace initiative taken by his Government had required enormous courage, sincerity of purpose and vision. It had also required a credible leader in whom the people could repose their trust and confidence. President Kumaratunga had not only matched words with deeds, she had displayed courage of the highest order in view of the fact that she had lost her father and her husband to assassins’ bullets. The President and the Government were well aware of the risks inherent in the peace process and of the entrenched suspicions and fears that years of conflict had engendered. They had to strike a cautious balance between the interests of the majority and minority communities, as well as within the minorities. A parliamentary Select Committee was currently charged with evolving the appropriate political structure within a united Sri Lanka.

His Government had given an undertaking to the people of Sri Lanka that it would promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms. To that end, it had rescinded the emergency regulations, with the exception of five which were essential for the maintenance of security. Even those five were applicable only to the Northern and Eastern Provinces and the bordering areas where security was still threatened. His Government had also established three separate commissions on a regional basis to investigate disappearances that had taken place since 1988. A newly appointed committee had already expedited the release of persons detained under the Emergency Relations and Prevention of Terrorism Act.

The powers of the Ombudsman had been strengthened and the public had been provided with unhindered access to him. Several deputy ombudsmen had been appointed to serve in the provinces. Arrangements had been finalised for the establishment of a national human rights commission. The Government had already ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and, in November 1994, had enacted legislation to implement it. In its determination not to tolerate violations of human rights, the State had already launched prosecutions in several key cases, thus sending an unmistakable signal to would-be violators.

His Government would continueto cooperate with local and international non-governmental organisations, international humanitarian agencies and United Nations organs such as the Commission. He had appointed a distinguished five-member group of experts from Sri Lankan non-governmental entities to advise him and to ensure that he remained abreast of international developments in human rights matters.

Since honesty and integrity in politicians and public officials were essential for the establishment and maintenance of good governance, his Government had introduced, among its first legislative and executive actions, amendments to the Bribery Act and had also appointed a new independent Bribery Commission.

His Government respected human rights at every level. At the national level, the constitutional reforms under way would expand the existing scope of human rights in line with internationally accepted standards. The pending legislation to establish a national human rights commission would constitute an important landmark in that regard. His Government would also play a constructive role at the regional level in an endeavour to create a collective expression of the commitment to human rights and fundamental freedoms, supporting as it did the proposal that an appropriate human rights mechanism for the region should be established. At the international level, it would continue to cooperate with the Commission and all other relevant human rights mechanisms of the United Nations, maintaining its policy of transparency and openness.

His Government attached the highest importance to all aspects of the Commission’s work. He mentioned, in particular, the preliminary report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, the establishment of the Working Group on the Right to Development and the initiatives taken by the Working Group on the Rights of the Child. In that connection, he was proud that Sri Lanka was the first Asian country to sign and ratify the Convention on Protection of Children and Cooperation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption.

He welcomed the fact that the Commission’s activities were expanding into various parts of the world and hoped that the High Commissioner for Human Rights would find time to visit Sri Lanka. He also hoped that the expansion of the Commission’s activities would lead to a cooperative and consensual rather than coercive approach to human rights issues and that such consensus would help consolidate all the efforts aimed at rationalising the Commission’s work.

His Government believed that the Commission’s agenda should reflect the totality of human rights and fundamental freedoms, including economic, social and cultural rights, as well as civil and political rights and the right to development. The fact that he himself, a lifelong campaigner for human rights who had once worked for Amnesty International in his country, had had the opportunity to address the Commission on behalf of Sri Lanka symbolised the country’s new approach to human rights, an approach which was fully in harmony with the Commission’s goals.