Why Sri Lanka should allow the exchange rate to strengthen

Sri Lanka’s bank credit is now weak and with other people’s savings no longer being spent by borrowers, external outflows are less than total inflows, which is putting upward pressure on the exchange rate.

The central bank however is not allowing the rupee to appreciate and is capturing the net savings as foreign reserves. This is pushing up liquidity in the banking system and pressuring interest rates down. There is no doubt that foreign reserves are needed, since repayments to the International Monetary Fund have kicked in, but that goal is not incompatible with a slightly stronger exchange rate.

Non-credible peg

The IMF in a recent press release following annual its Article IV consultations said that Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange regime has been classified as ‘stabilised’ from ‘managed float’.

There is little to choose between the two. The bottom line is the rupee had been re-pegged at about 130 to the US dollar from about 110 before the 2011/2012 balance of payments crisis.

Whether called ‘managed floats, ‘stabilised’, ‘crawling pegs’, or ‘crawling bands’ such arrangements are ultimately soft or non-credible pegs.

The peg is not credible or is soft because at any time the monetary authority could print money and de-stabilise it by generating extra domestic demand and imports, even if exchange controls are in place to stop capital flight.

Sri Lanka has had a soft-pegged exchange rate from 1950 when the Central Bank was created. Before that a hard peg or currency board existed where the exchange rate was fixed as the state could not print money.

But after independence when the Central Bank printed money to finance deficit spending, or even to keep private credit up to get more ‘economic growth’ (depressing interest rates through policy rate injections), the rupee has come under downward pressure Pseudo-Credibility

One worry expressed by the IMF is that market participants will attribute the current soft-peg with some pseudo-credibility and start to act accordingly, by borrowing heavily abroad, exposing themselves to forex risk when the rupee subsequently falls

“First, it may create the perception that the rupee is implicitly fixed—a point supported by the shift in exchange rate classification from ‘managed float’ to ‘stabilised’ under the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Rate Arrangements,” an IMF Executive Board assessment said.

“This perception could lead market participants and firms to hold un-hedged foreign exchange risk on their balance sheets.”

The IMF also said the following: “Second, should external balance continue to improve and inflation stay low, it could gradually lead to increasing currency misalignment. The central bank should thus be prepared to allow sufficient exchange rate flexibility to adjust to fundamental pressures, while limiting intervention to accumulation of reserves and smoothing short-term volatility.”

Whether an exchange rate has some mysterious ‘fundamental’ level or that it is ‘undervalued’ or ‘overvalued’ is a separate debate. As the Reserve Bank of India Governor said in Colombo recently currencies did not move before the World Wars because there was a single monetary anchor for most of the world – gold.

But it can be easily shown that the rupee did not fall from around 110 to the dollar and ended up around 130 due to any fundamental mystique but due to the inevitable consequence of specific central bank domestic and foreign currency operations that were applied at specific times.

Operational Track

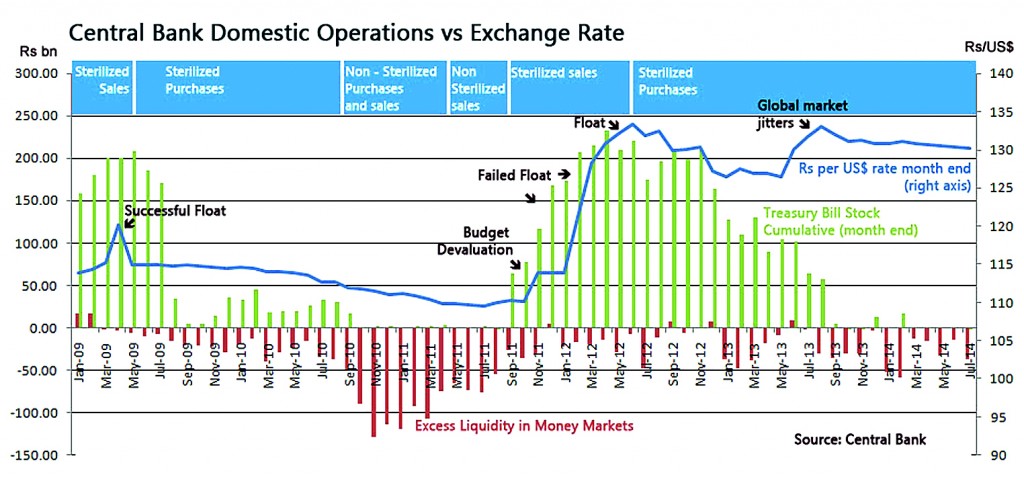

If the Central Bank’s operational procedure is tracked through the last two balance of payments crises, several variations can be seen.

During the earlier crisis up until May 2009 Sri Lanka was engaging in sterilized foreign exchange sales where dollars were sold for rupees by the Central Bank amid some capital flight.

A dollar sale by a central bank – unlike any other market player – creates a domestic currency shortfall in money markets triggering a contraction in base or reserve money (money in circulation and cash deposited by banks in a central bank), putting upward pressure on interest rates.

To counter higher interest rates, a pegged central bank will inject cash (print money) through Treasury bill purchases to offset the tightening effect of the dollar sale on money markets and credit. But that action will help fuel fresh credit and demand and thereby imports. Such sterilized forex sales gives rise to a vicious cycle which is generally called a balance of payments crisis.

Around May 2009 (the spike in the graph) the rupee was floated ahead of an IMF bailout and interventions and liquidity injections were ended to halt the rupee slide.

Sterilised Forex Purchases: Following a successful float and confidence restored by an IMF bailout, liquidity generated from forex purchases were steadily withdrawn amid weak credit, in a process of sterilised foreign exchange purchases. This resulted in a gradual fall in the total Treasury bill holdings or domestic assets of the Central Bank and a rise in foreign assets.

Non-sterilised purchases and sales: Around the last quarter of 2010 the Central Bank suddenly allowed liquidity to remain in money markets after buying dollars, with foreign reserves at high levels.

A period of mainly non-sterilised interventions (purchases and sales of dollars with rupee liquidity allowed to move up or down) then followed, which is similar to that seen in currency board regimes.

Non-sterilised Sales: Around the second quarter of 2011 and onwards, interventions started to become one-sided (non-sterilised foreign exchange sales), as state banks began financing the losses of CPC and CEB with rupee loans to import oil. This can be seen by the sharp one-sided reductions in money market liquidity in that period.

By September, the banking system was out of liquidity and non-sterilised interventions could no longer be performed and fresh liquidity had to be injected. The residual excess liquidity of around 15 to 20 billion rupees seen in the graph (bars below the x-axis) came from foreign banks which had some cash parked in the Central Bank.

Sterilised Foreign Exchange Sales: From around the third quarter of 2011 a period of liquidity injections and forex sales (full blown sterilised foreign exchange sales) began.

Dollar Defence

Until November 2011 however the exchange rate itself was kept unchanged through full currency defence on all dollar transactions.

In money markets, sterilisation may have been full (100 percent) or partial from time to time. When interest rates move up, sterilisation is partial.

Full Dollar Defence: Such a situation can be characterised as ‘full currency defence and partial or full sterilisation’. Despite an unchanged exchange rate, there was uncertainty in forex markets and exporters held back dollars and the credibility of the peg was lost.

In November 2011, through the budget, the exchange rate was depreciated by fiscal decree suddenly to 113.90 rupees from 110 to the US dollar.

But until February 2012 full foreign exchange defence was conducted amid sterilisation to defend the rupee at around 113.90 to the dollar as can be seen in the chart by the absolutely flat section of the curve.

Float: In February 2012 the rupee was floated following an IMF mission visit. Floating should have meant the end of interventions and sterilisations. Under a floating regime, with no liquidity injections required, no fresh demand is generated, and the exchange rate stabilises at a weaker level, perhaps after overshooting.

(In a floating regime the liquidity injections occur only through standard domestic market operations since there are no interventions in forex markets. That is why when policy rates are raised exchange rates strengthen).

The period immediately following the float in 2012 was the most deadly to the rupee, as the float failed to take effect quickly unlike in April/May 2009.

Partial defence, full sterilisation: The problem was that the Central Bank continued to partially intervene (and sterilise) to help pay oil bills, while allowing other forex transactions to go at an ever weakening market rate as required by the injected rupees, when overall credit was still strong.

The operational procedure therefore shifted to what can be characterized as ‘partial currency defence and rupee sterilisation.’

Partial defence and full or nearly full sterilisation is the most deadly operational procedure for any central bank to pursue.

That is why the rupee went sliding down to around 132 to the dollar in a short time. Under partial defence and full sterilisation, there is no bottom to where a currency may fall.

There are no ‘fundamental’ conditions in the broader economy to determine an exchange rate under such a procedure. The currency falls until interventions are halted. If interventions were halted earlier, if electricity prices were raised earlier and state bank credit volumes reduced earlier, the rupee would have ended up -say – at 118 or 120 or 125 to the US dollar.

Two Reasons

Understanding why the rupee fell faster in this period and not earlier is important for two reasons.

First, it shows that there was no mysterious underlying ‘economic fundamental’ that magically carried the rupee to 130 to the dollar and kept it there other than a money-and-credit issue involving the banking system.

What is more important however is the impact of such a steep depreciation on people and firms, who collectively make up what is called the ‘economy’.

Steep currency depreciation destroys the value of money and the salaries and lifetime savings denominated in that unit.

When currencies are steeply depreciated, domestic demand collapse. People are suddenly poorer and it will take longer for domestic demand to recover than if the rupee regained some or all of the lost value.

Then exports are the way out of the hole. Exports are boosted – if there is sufficient external demand – simply by cutting the real wages of workers through inflation and depreciation.

In the meantime people suffer, and the political consequences can sometimes be seen in elections.

It is peculiar and laughable that economists and financial analysts talk about foreign investors in Treasury bills making losses when the rupee falls. But local investors, pension funds, the employees’ provident fund and all bank depositors – big and small – also suffer exactly the same fate.

Currency depreciation is the most potent and deadly tool developed by European rulers with state-owned central banks to impoverish the population.

More than through high taxation, denying opportunities to the general citizenry through monopoly powers given to favoured state or other businesses, expropriation, more than even trade restrictions and autarky, currency depreciation is a sure fire way rulers and interventionists can quickly impoverish the general population and wage earners in particular.

Unsound Money

A country cannot escape the so-called ‘middle income trap’, through currency depreciation. There is no need for businessmen to produce high value products or services by boosting labour productivity, if real salaries are cut through currency depreciation and inflation.

Labour productivity is boosted through capital investments. If capital is destroyed through currency depreciation where are the funds to invest? Then a country has to become even more dependent than otherwise on foreign direct investments.

It is a fallacy that countries with stable or strong exchange rates cannot export or have trade deficits. Trade gaps are a consequence of savings propensities not exchange rates.

Japan’s exchange rate was stable around 350 yen to the dollar following World War II. After the break-up of the Bretton Woods system it continued to appreciate through the 1970s and 80s, ending up around 145 by 1990.

The same applies to Germany, another global export powerhouse. In 1971 a dollar was worth 3.6 Deutsche Marks. By 1990 a dollar was worth only 1.7 Deutsche Marks. Since exchange rates are relative, keep in mind that the US (which had a chronic trade deficit) actually had a ‘weaker’, exchange rate than Japan or Germany.

Singapore has had a strong exchange rate which has steadily appreciated over the US dollar. After 1982 Hong Kong has had a hard peg or currency board with the rate absolutely fixed with the US dollar.

China’s exchange rate has appreciated over the last decade, pushing up living standards of all the people.

In East Asia, Indonesia still has a ‘crawling peg’ and suffers some of the highest inflation and weakest currencies compared to the region, as well as significant poverty, despite being oil rich.

Vietnam, an impoverished chronic currency depreciator, changed course after the East Asian crisis and saw its poverty plunging and exports soaring during the following decade. From 2008 it was hit by a bursting domestic and global credit bubble and the currency plunged. The economy is still struggling to recover.

One of the good economic policies of the current regime has been a commitment to keep the exchange rate strong and consequently inflation low.

A strong exchange rate maintained by prudent and non-contradictory monetary policy, which will also keep overall domestic inflation low is the best bulwark against poverty.

There is no path to prosperity through unsound money.

(This is a new column that would deal with a range of economic and monetary policy issues. The writer is a long-term observer of Sri Lanka’s economy. He could be reached at bornfreebt@gmail.com)