News

Alarm over rising seas but villagers keep returning to risky shore

For Shanthi of the Sri Dharmaarama Road fishing village in Ratmalana and Kamala Fernando of Ransigamawella off Wennappuwa, the coming days are a struggle to protect their houses from the strong waves that are rapidly swallowing up the shore.

Thousands of families living bordering the south-western coasts and north-western coasts are at a growing risk of coastal erosion, experts fear.

The latest danger was reported in Ratmalana where about 20 houses were destroyed with chairs, mats, pots and pans of poor fishing families sailing away with the waves.

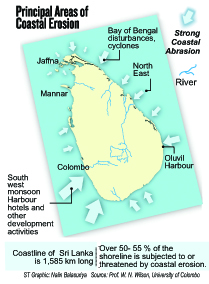

Prof. W.N. Wilson, senior lecturer in geography at the Colombo University, said more than half the country’s population lives in coastal areas and the coastline from Kalpitiya to Tangalle is more prone to coastal erosion-related disasters.

Sea erosion in Ransigamawella, off Wennappuwa. Pix by M.A. .Pushpa Kumara and Rekha Tharangani Fonseka

He said the beaches of Mt. Lavinia, Ratmalana, Wellawatte, Wattala, Poruthota, off Wennappuwa, Marawila, Kalpitiya, Weligama, Beruwala, Ahangama, Hikkaduwa and Unawatuna would be more affected by erosion due to human-made factors and natural factors such as the south-west monsoon, disturbances in the atmosphere, rough seas and strong currents.

He said crystalline rocks, corals, beach sand and rock debris found in the coastal terrain acted as natural barriers but these were being destroyed in places.

“Coral mining, mining in rivers and estuaries, rock-blasting to build harbours, drilling into coastal soil layers to build hotels, apartments etc. are among the leading causes for the increased coastal erosion,” Prof. Wilson said.

“Coral mining, mining in rivers and estuaries, rock-blasting to build harbours, drilling into coastal soil layers to build hotels, apartments etc. are among the leading causes for the increased coastal erosion,” Prof. Wilson said.

If another tsunami struck, the western and southern belts would experience greater destruction due to increased development activities and settlements bordering the ocean

“With natural barriers destroyed and coast eroding one metre annually, strong waves can easily enter the land. Environment impact assessments and vulnerability studies should continue with erosion prevention given priority. Most of the wooden groynes, structures built out from seashore to control erosion, were destroyed by the 2004 tsunami,” he said.

Prof. Wilson said the northern parts of the country were vulnerable due to turbulences and rain disturbances in the Bay of Bengal.

Thousands of families live along the southern and western coasts that are highly vulnerable to coastal erosion.

Swarna Perera, member of a 300-strong fishing community off Negombo, said she is currently living in her ninth house with all previous houses, whether built of brick or wood, lost to the sea.

“Where are we supposed to go?” she asked. “The authorities give us money but that is not sufficient to buy a plot of land and build a house.”

Kamala Fernando, a resident of Ransigamawella, a coastal village off Wennappuwa, said during the 40 years the sea had encroached about 300m into the land.

“There used to be so much space for me to rear pigs and poultry. Now there is no space at all. After the tsunami, coastal erosion

Kamala Fernando

accelerated,” said Kamala, whose house is on the border, with strong waves hitting the temporary walls made of dried coconut leaves.

Last week’s sea erosion heightened by strong waves damaged 18 houses out of 60 in the coastal village along the Ratmalana coastline. According to the Disaster Management Centre (DMC), the erosion affected 355 persons in 85 families.

Mangala Wickremanayake, Director General of the Department of Coast Conservation Department (CCD), the main body in charge of ensuring the protection of the coast said building harbours had adverse impacts on the coast in adjacent areas, and constant monitoring and erosion prevention measures should be taken.

She said the Oluwil harbour had caused coastal erosion in surrounding areas in the east, and solutions such as offshore breakwaters and groynes had to be continuously maintained and monitored.

She said the Colombo port expansion project would have more coastal erosion impact towards the north than the south.

“The Wennappuwa, Marawila, Kalpitiya shorelines are severely affected due to many years of sandmining in Maha Oya that is finally prohibited. Sand nourishment is taking place with sand being pumped last year, and with the increasing erosion we will be doing it next year as well,” she said.

According to Ms. Wickremanayake, development activities, including the construction of tourist hotels, should be carried out only after obtaining permits from the Coast Conservation Department.

The permit application has criteria including whether the area has been subjected to erosion in the recent past, and these will be investigated by the CCD before issuing a permit, she said.

Under the CCD Act “development activity” is defined as “any activity likely to alter the physical nature of the Coastal Zone in any way, and include the construction of buildings and works, the deposit of wastes, other materials from outfalls, vessels or by other means or removal of sand, coral, shells, natural vegetation, sea grass or other substances, dredging and filings, land reclamation, and mining or drilling for minerals, but does not include fishing.”

Ms. Wickremanayake said at present, hotel projects in coastal areassuch as Negombo and Unawatuna had caused soil erosion.

She also said the destruction of houses in the Ratmalana sea erosion incident was due to the residents building unauthorised constructions on sand dunes.

“Under the Coast Conservation Act we can take extreme measures and stick to the no-build zone of 100m. But political pressure has led us to limit the use of our powers due to the vote bank. Despite providing them with housing schemes and handing over money, families still settle near the shore,” she said.

Dr. Jagath Munasinghe, a senior lecturer at the Department of Town and Country Planning at the University of Moratuwa and Secretary to the Institute of Town Planners, said previously institutions relating to town planning such as the Urban Development Authority (UDA) lacked power to take action and there were insufficient technical officers to provide advice or guidance, unlike today.

“With the increased coastal erosion there is a need for proper infrastructure for these fishing families. Workstations should be built for fishermen so their boats and fishing equipment can be stored safely while their houses should be moved away from the risky sea shore.

“Law enforcement is a must. The first generation will complain but gradually they will move to better settlements,” he said.

The Sunday Times learns that some affected families had received Rs. 500,000 when their houses had been previously washed away and some residents also received houses at housing schemes in Ratmalana.

The villagers allege, however, that the houses had been provided to supporters of local politicians, with some owning 10-15 housing units.

Last week, a new Asian Development Bank (ADB) climate and economics report for South Asia said the country’s vast and diverse coastal region, covering nearly a quarter of the island, is likely to see serious damage to fisheries and coastal ecosystems from more frequent storms and a potential one metre rise in sea level, which would badly affect the Jaffna and Gampaha districts, which include several coastal areas affected by erosion.

The report said the country should respond to climate threats by adopting saline-resistant crop varieties, more integrated coastal zone management, increased efficiencies in the energy sector, improved disease and vector surveillance, more protection of groundwater resources and greater use of recycled water.