Sunday Times 2

Violence, threats prompt more Muslim women in Britain to wear a veil

LONDON, (Reuters) – When youth worker Sumreen Farooq was abused in a London street, the 18-year-old decided it was time to take a stand — and she started to wear a headscarf.

Farooq is one of many young Muslim women living in Britain who have, for various reasons, chosen to adopt the headscarf to declare their faith to all around them, despite figures showing rising violence against visibly identifiable Muslims.

Shanza takes photographs during her sister's traditional Islamic wedding blessing held at home in Walthamstow, east London. Shanza and her sister Sundas both faced a lot of opposition to their wearing a veil, particularly from their mother, who doesn't cover her head and didn't like this strict interpretation of Islam. Reuters

For despite a common view that young Muslim women are forced to wear veils by men or their families, studies and interviews point to the opposite in Muslim minority countries where it is often the case that the women themselves choose to cover up.

“I’m going to stand out whatever I do, so I might as well wear the headscarf,” said Farooq, a shop assistant who also volunteers at an Islamic youth centre in Leyton, east London.While just under five per cent of Britain’s 63 million population are Muslim, there are no official numbers on how many women wear a headscarf or head veil, known as the hijab, or the full-face veil, the niqab, which covers all the face except the eyes. The niqab is usually worn with a head-to-toe robe or abaya.

But anecdotally it seems in recent years that more young women are choosing to wear a headscarf to assert a Muslim identity they feel is under attack and to publicly display their beliefs.

Shanza Ali, 25, a Masters graduate who works for a Muslim-led non-profit organisation in London, said she was born in Pakistan and her Pakistani mother had never worn the veil but both she and her sister Sundas chose to do so aged about 20.

“I decided to make a commitment as a Muslim and I have never stopped since,” Shanza told Reuters in her family home in Walthamstow, east London where prayer mats hang from the walls alongside modern, family portraits.

“Sometimes you forget that you’re covering your hair but you never forget why you’re covering. You remember, that to you, your character should be more important than your appearance.

“It makes it easier for Muslim women to keep away from things that you don’t want to do that would impact your value system. If you don’t want to go clubbing, drink, or have relations outside marriage, it can help, but it can also just be a reminder to be a good person and treat others well.”

Standing out in a crowd

Shaista Gohir, chairman of the Muslim Women’s Network UK, said more women had adopted headscarves since the attacks in the United States on Sept. 11, 2001, and in London on July 7, 2005, put them under greater political and public scrutiny.

“For some young women it is a way of showing they are different and they are Muslim although it is not a Muslim obligation,” she told Reuters.

She said the full-face niqab was a minor phenomenon in Britain, worn by relatively few women, although it had become central to a wider debate in the country about integration and British values.

This was put to the test last year when a judge ruled a Muslim woman could not give evidence at a trial wearing a niqab, sparking debate about whether Britain should follow other European countries and ban full-face veils in public places.

After a national debate, a compromise was reached and it was agreed that the woman could wear the niqab during the trial but not when she was giving evidence.

Modesty in Islam is key for both men and women but most Islamic scholars agree that women adopting a full-face veil is more to do with culture than religion.

But women who publicly display their religion by wearing a scarf of any kind have found they can be targeted for doing so.

Figures released recently from the campaign group Tell MAMA (Measuring Anti-Muslim Attacks) showed the number of attacks against Muslims in Britain was on the rise. During its first year of monitoring, Tell MAMA recorded 584 anti-Muslim incidents between April 1 2012 and April 30 2013, with about 74 per cent of these taking place online.

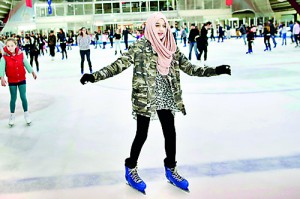

A Muslim girl, 12, ice skates in east London. Reuters

Of the physical incidents, six in 10, or 58 per cent, were against Muslim women and 80 per cent of women targeted were visually identifiable by wearing a hijab or niqab.

The number rose to 734 incidents over the 10 months from Mary 2013 to February 2014 with 54 per cent of these against women and a total of 599 online. There was a spike in reports in the weeks following the murder of off-duty soldier Lee Rigby in south London in May last year by two British Muslim converts.

“Attacks against visibly dressed Muslim females may not accurately explain away the trend of hate crimes being opportunistic and situational. The data suggests that the alleged perpetrators of anti-Muslim hate crimes at a street-based level, are young white males targeting Muslim women, and that is a cause for concern,” Tell MAMA said in a statement.

Matthew Feldman, co-founder of the Centre for Fascist, Anti-Fascist and Post-Fascist Studies at Teesside University who analyses Tell MAMA data, said the rise in the numbers of attacks could be partly due to more awareness of the reporting process.

“But there is a slight bump in the occurrence of people wearing more visible dress and of victims being women rather than men,” Feldman told Reuters.

“We are seeing an unacceptable rise in the level of anti-Muslim attacks but it does seem there is a pretty small number of violent, hardcore far-right people responsible for a high number of these.”

Violence does not stop the veil

He said it was surprising but reassuring that the rise in violence against Muslim women had been accompanied by a rise in the number of women adopting the veil.

This was also the conclusion of a study last year by the University of Birmingham that found over 15 years Muslim women had repeatedly been shown to be disproportionately targeted in relation to anti-Muslim hatred as they were identifiable.

None of the women attacked, however, had stopped wearing a veil as a result.

Yasmin Navsa, 17, a student from Hackney in east London, said wearing a hijab made her stand out and made her different.

“In Islam it doesn’t say anywhere you have to wear a veil but it’s a choice. It’s more fashionable now with different colours and styles which makes it more attractive to wear,” Navsa told Reuters in a break from exams.

“I’ve found it’s so common to wear a headscarf now in London that you don’t get looked at twice any more but I think wearing a full-face veil would attract some negative comments.” This approach to adopting the hijab with a view to being identifiably Muslim was typical in Muslim minority nations but not in countries where Muslims are in the majority.

An international study in 2012, conducted in Austria, India, Indonesia and Britain, looked at Muslim women’s views on wearing a headscarf in Indonesia which is a Muslim majority society, compared to India that is a Muslim minority.

It found that in a majority, women talked about convenience, fashion, and modesty as reasons for veiling.

But in minority communities, women’s responses were more diverse, ranging from religious arguments to convenience and to opposition against stereotypes and discrimination.

“For women in minorities the veil was a way to affirm their cultural identity and a political and resistant way to address negativity about Muslim communities,” said researcher Caroline Howarth, from the London School of Economics.

“This does contradict the view dominant in non-Muslim countries in the West that the female scarf is a symbol of religious fundamentalism and patriarchal oppression.” Sundas Ali, 29, said her husband, whom she married last year after an introduction between their families, made it clear to her from the outset that wearing the hijab was her decision.

She said some young Muslim women even received kickback from some men for wearing a headscarf as they were seen as “boring, unfashionable, and no fun”.

“There is a misconception that it is the men telling the women what they should wear but for me and all my friends this is just not the case,” Sundas, an Oxford university graduate with a PhD in sociology, told Reuters.

“My husband left it up to me as he doesn’t practise ritualistic religion. We both have a mixed identity, our religious, ethnic, and national identities are all important to us. His eastern side really appealed to me but also the fact that he is quite liberal, in an open-minded way. We really are the modern Muslim generation.”