Creating the next generation of innovators

An invention by Suranga and his team - the EyeRing a finger worn camera allowing users to verbally instruct the system to perform recognition and interpretation of what the camera sees

As a young boy, Suranga Nanayakkara would watch his mother-an electrical engineer-tinkering around the house with fascinated eyes. “I found myself wondering how various devices worked, and often found myself lost in daydreams about the people who invented them,” he says.

Many years later, Suranga has become one of those people that he used to dream about-an Assistant Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), former visiting Assistant Professor and Postdoctoral Associate at the Fluid Interfaces group, MIT Media Lab and more importantly, an inventor keen on changing the landscape for interaction between human touch and technology. He‘s come a long way from that young boy who spent his time daydreaming.

Suranga studied at Royal College, Colombo, and although he had initially planned to attend a local university, it was his teacher who prompted and supported him to apply to a foreign institution. “My cousin, who was teaching in a polytechnic in Singapore suggested that I apply for a scholarship at the National University of Singapore (NUS),” he says over an email interview with the Mirror Magazine.

Suranga studied at Royal College, Colombo, and although he had initially planned to attend a local university, it was his teacher who prompted and supported him to apply to a foreign institution. “My cousin, who was teaching in a polytechnic in Singapore suggested that I apply for a scholarship at the National University of Singapore (NUS),” he says over an email interview with the Mirror Magazine.

Suranga applied and was accepted to study electronics and computer engineering. “I then wanted to go into a field of research that would help me to apply and exercise the analytical as well as creative skills that I acquired through the years.” For his PhD, Suranga began exploring ways of providing a satisfying musical experience to the hearing impaired. Inspired by the words of world famous percussionist Evelyn Green, a musician who also happened to be deaf, Suranga designed the Haptic Chair, a wooden chair that vibrated to the music flowing from the speakers embedded into it. He collaborated with Savan Sahana Sewa, a school for the deaf in Moratuwa; the Haptic Chair received very positive reviews from the children, and has now been in use for over five years enabling communication between students and teachers.

Suranga with an EyeRing. Pix courtesy Suranga Nanayakkara

It was following this, during a conference in Boston, that Suranga met Professor Pattie Maes who directs the Fluid Interfaces Group at Media Lab. Impressed with his work, she offered him a postdoctoral position in her group. “This was a game changer in my research career,” he notes. The MIT Media Lab was the playground for the creation of products such as the Amazon Kindle, LEGO Mindstorms and MPEG-4 Structured Audio. “I met and worked with some amazing researchers,” he says. “For example, Pranav Mistry-who conceptualised the Samsung Galaxy gear smart watch- and I worked on a project that allowed a user to transfer media from one digital device to his or her body and pass it to the other digital device by simple touch gestures.”

It’s this abiding interest in enabling human computer interfaces as natural extensions of the human body, mind and behaviours that sees him working in a research direction at SUTD. His research and development work is focussed on a hybrid of Augmented Reality and Assistive Technologies-he calls ‘Assistive Augmentation’.

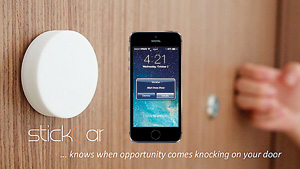

Two developments by his team, the EyeRing (a finger worn camera that allows users to verbally instruct the system to perform recognition and interpretation of what the camera sees) and the StickEar (a network of distributed ‘sticker-like’ sensor nodes that enable sound-based interactions on everyday objects) have been lauded by his peers and received positive feedback. “These are initial steps towards my broader vision of creating interfaces to enable people, connecting communities with different capabilities through technology, empowering them to go beyond what they previously thought they could do,” he shares.

“With publications in top conferences, demonstrations, patents, media coverage and real world deployments, I have been exploring and pushing the state-of-the art in Assistive Human Computer Interactions. I like to think my passion has given a ray of light to the blind, and a rhythm to the lives of the deaf.” In facilitating assistive device technology for the visually and aurally impaired, Suranga finds that the effort must be more focussed on not just overcoming their setbacks but also enabling more than the user thinks they are capable of. “For example, EyeRing is not a specialised device for the blind to overcome their deficiencies. It is a universal device useful for everybody-both blind users and sighted children and adults.

“I think this kind of device has the potential to be much more socially acceptable than just doing dedicated assistive devices with the assumption that hearing-impaired and visually impaired people are incapable.” As a teacher at SUTD he wanders off the beaten track to facilitate a whole new learning experience. “The digital generation has the ability to find all the information independently; hence, information style lectures become less and less relevant,” he muses. “In my classes, I offer an environment for experience based learning, allowing students to explore cycles of theory, design, prototype, and testing hypothesis.

Overall, my aim has been to help students to grow through creativity to become the next generation of innovators and I would like to be remembered for inspiring the strong to become leaders and the weak to become strong.” As a beneficiary of his home country’s free education system, Suranga is keen to contribute where he can and keeps a close eye on developments back home.

In Sri Lanka the landscape looks promising, but perhaps universities could benefit from more industry oriented syllabuses, he points out. “I think our education ecosystem could improve. We need to make closer connections between our university system and industry needs.”