Suicide as a problem solver: Time to say no, no, no

Rid this country of the ‘culture’ of suicide where there is acceptance of harming oneself as a way of sorting out the problems that life throws at us.

This is the urgent and fervent appeal from Consultant Psychiatrist Dr. Mahesh Rajasuriya as World Suicide Prevention Day is commemorated on September 10 and reports flow in of different types of suicides and attempts, even though self-preservation is the core of any living being, either human or animal.

Sri Lanka is ‘unique’, although sadly it is nothing to be proud of when considering suicides, the Sunday Times learns.

While across the world those who usually attempt to take their lives fall into the older age-group (those more than 50 years old) who are assailed by debilitating physical or mental illnesses, alcohol abuse and also isolation and loneliness, which are high risk factors, the picture varies dramatically in Sri Lanka, it is understood.

There is a “huge peak in the young”, points out Dr. Rajasuriya, adding that in Sri Lanka, the suicide epidemiology is different. “We have a significant peak among those in the 15 to 25 year age-group.”

Dr. Rajasuriya who is also a Senior Lecturer at the Colombo Medical Faculty speaks with evidence in hand. A research done by him in 2009 in the Ampara district of 230 people who attempted to take their own lives had found that only 7.4% were above 49 years but a shocking 70.4% were below 30 years old. In Ampara the attempts had been 406 per 100,000 per year, 20 times more than the national suicide rate of that year.

“These are atypical suicide attempts, for they just don’t fit the bill of those at high risk with physical or mental illnesses or significant substance abuse,” he says.

These spur of the moment or instant reactions to an event in a young life such as a love-affair going awry, being reprimanded by an adult, a severe argument with a parent or failure at an examination, cannot be foreseen, monitored or prevented, but what is essential is to root out the ‘suicide culture’ in which such action is deemed to be acceptable, according to Dr. Rajasuriya.

“When someone close to us faces such a situation, the best way to handle it is to try and delay the knee-jerk reaction at least for a few hours but preferably a day. As the distress becomes less, so does the impulse to do something drastic. The distress does not go away immediately but with the passing of time it lessens,” he says.

Suicide methods too should not be discussed at length as these can be used as a learning tool by the vulnerable with a severe adverse impact, he reiterates, adding that it is of paramount importance for the media to report suicides with responsibility.

Dealing with what ‘suicide culture’ means, this Psychiatrist says that it is “a pattern of behaviour and beliefs where suicides are accepted and promoted as a method of sorting out issues in life”. Citing a hypothetical case where a boy is admitted to hospital after overdosing himself with medication, Dr. Rajasuriya says that those around him may question why he attempted to harm himself. If he says it was due to an argument with his mother, someone may react with “okatada karagaththe” (was it just for that), implying that attempting suicide is acceptable for some  other problem. This should be a definite “No, no”.

other problem. This should be a definite “No, no”.

The other need of the moment is not to make those who commit or attempt suicide seem heroic, talk highly of them or create the impression that it can be used as a weapon to gain some benefit, it is learnt.

If someone attempts suicide, demanding something, for example a bicycle from his parents and he is given one after the attempt, his siblings and peers will assume that attempting suicide is an easy way to gain one’s demands. This too should not be encouraged.

Delving into history, he refers to the time before and when Sri Lanka had the dubious reputation of being No. 1 on the list of countries with the highest rate of suicides.

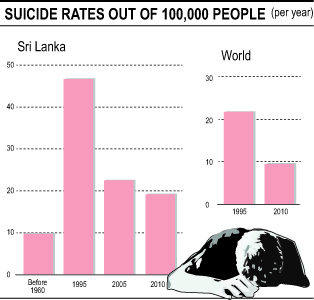

The rate of suicides in Sri Lanka was under 10 per 100,000 per year before 1960, with a steady increase after the 1980s and by the mid-1990s hitting the highest notch in the world with an estimated 47 per 100,000 per year in 1995.

The assumptions are that the initial increase in the figures after the 1960s was due to improvements in reporting, while the dramatic increase in the 1980s and 1990s came with the open economy and the abundant availability of agro-chemicals, the Sunday Times understands. However, the methods of suicide have changed over the decades.

The world’s average suicide rate is estimated to be 9.8 per 100,000 per year for 2010, with a notable factor being that there has been a steady decline in Sri Lanka, with 2005 seeing a halving of the 1990s figure to 23 per 100,000 per year and a further drop to under 20 thereafter.

Dr. Mahesh Rajasuriya

To the query why the numbers have dropped, Dr. Rajasuriya’s answer is that it was due to the “landmark” appointment of the Presidential Task Force for the Prevention of Suicides in 1996 which came up with wide-ranging recommendations such as the banning of the most lethal agrochemicals and dilution of other agro-chemicals while also making them more repulsive odour-wise and induce vomiting, which were implemented.

Another major recommendation of the Presidential Task Force had been sensible and responsible reporting on suicides by the media, with Guidelines being introduced. With better reporting, a decline in suicides had been recorded, he says.

Although the latest figures, those for 2010 are 19.6 per 100,000 per year in Sri Lanka, there is still cause for concern as the decline in suicide numbers has reduced and slowed. “We are still among the world’s top 20. Therefore, now is the time to dispel the suicide culture to try and cut the numbers more,” urges Dr. Rajasuriya.

| The older generation: Watch out for these signs

How can the smaller but older group of people with vulnerabilities such as physical or mental illnesses, a tendency for substance abuse or loneliness who may be determined to take their lives be prevented, from doing so? “This group is in the high-risk category,” stresses Dr. Rajasuriya, explaining that some of them take a decision to terminate their own lives and usually plan carefully while taking precautions to avoid discovery. They may suddenly write up a will, call an old friend and bid goodbye, write a letter or note and give away possessions. If those around him/her have a suspicion and a person expresses a wish to die, there is a need to take the situation seriously and not scoff at it. A quiet chat on how they feel may elicit some information, with a need to deal tactfully with gloomy answers. Sumithrayo will help you make the choice to live The primary object of Sumithrayo, a voluntary service organisation is helping people who are lonely, distressed and in despair and with suicidal feelings. Though the incidences of suicide in Sri Lanka have greatly reduced since 1995 with 47 deaths per 100,000, Sri Lanka has no reason to be complacent as the number of attempts have now alarmingly increased almost to twenty times as the number of deaths, a release from Sumithrayo states. Apart from centre based befriending (callers who visit, phone, write or email), Sumithrayo volunteers also do “outreach work”. They conduct awareness programmes about suicide prevention and other social concerns, to various working groups and institutions both in the state sector and private sector. In hospitals where attemptees are warded, Sumithrayo befriend them and their families regularly. Volunteers also visit elders’ homes, children’s homes and even prisons. The Rural Suicide Prevention Programme set up in 1996 works in 90 suicide prone villages in the North Western and Southern Provinces and reaches out to some of the most vulnerable and despairing people in these areas. Sumithrayo volunteers who dedicate themselves to this humanitarian service are carefully selected for their caring disposition and are well trained. They remain anonymous wherever possible. The service is entirely free of charge. It becomes everyone’s responsibility to help our distressed fellow human beings to choose to live and not to die. Call Sumithrayo on 011 2692909. |