On the streets where he stencilled

The stencil of a smiling child is sandwiched between a photocopy shop and a dilapidated building on Dawson Street, while the alley in Vauxhall Street, dotted with bird droppings and peppered with buildings as colourful as its residents, plays host to one of the leading names in the international street art scene.

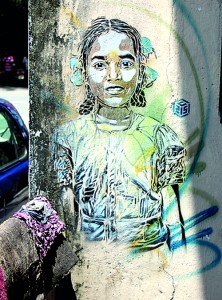

Culturally attuned: Portrait of an old woman and young girl (below). Pix by Adilah Ismail

As we wind our way through the back streets of Colombo 2, discarded ceramic bathroom fittings and a clothes rack form a foreground for a stencil of a tousle-haired, techni-coloured child. Try your luck and you’ll be invited to view the stencilled tusker with hot pink highlights reigning supreme inside an ochre living room while next door, Kanchana shyly poses underneath a stencil of a young girl in her hall (“I chose the design and asked him to paint it. I plan on keeping it until we perhaps decide to paint the house in the future”). Inch closer and you spot the artist’s calling card in all the stencilled graffiti–a neat cube formed with the characters ‘C215’.

When we meet late in the evening, the only vestiges of Christian Guémy’s hectic day are the faded paint smears blotting his fingertips and the fatigue of a day’s painting lightly traced on his face. Parisian stencil artist Guémy, who goes by the moniker C215, quietly entered the street art scene nine years ago. He has since painted his way across continents, displaying and creating his work in India, UK, Turkey, Italy, France, Brazil, Haiti, Ireland, Greece, Jamaica and now, Sri Lanka.

Guémy’s subject matter is one that varies, sometimes celebrating various aspects of the human nature – from love, frailty and vulnerability – in all its tumultuous glory and sometimes, the occasional depiction of cats (“Stencil art has a long history of almost 40 years. Most of the artists have a symbolic animal and I’ve been representing myself as a cat.”). His recurring muse however is his 11-year-old daughter Nina, mooring his work to a fiercely personal anchor. What started off as love letters to his daughter and a father’s poignant response to a sombre personal catalyst

Look, what he’s doing: A curious crowd watches Christian Guemy at work.Pic by Laura Lacour

and heartbreak, slowly created ripple effects and launched what has now grown to be a multi-hued international career in public art. Nearly a year after he began, Christian found himself in group shows in UK and caught the attention of the reclusive street artist, Banksy, nudging him into an international spotlight. Christian explains that now, Nina sometimes accompanies him on his travels whenever she has holidays and is also adept at painting. “This year we’ve been to Tunisia, Turkey, twice in Roma, London and Jamaica in March. In one year that’s what I’ve been doing with my daughter. We’re quite used to airports,” he smiles.

Over the years, Guémy’s artistic oeuvre has evolved in to a vivid, multi layered (the final work is often a culmination of several layers of colours atop each other) body of work, bringing in elements of chiaroscuro and detail rare in such a genre. He remains both pragmatic and philosophical about the ephemeral nature of street art. Perhaps in one sense, the transience of street art and its eventual decay, is balanced with its digital distribution and documentation.

Guémy’s brand of public art is one that is respectful to its surroundings and is careful not to offend. “I do not want to pain anyone. I’m not a vandal. I do nice things and I do not want people to be upset. I want people to be happy – that’s why I do it,” he asserts adding that it would be discourteous to paint in a place where people would not want you to paint. However, he is inclined to make an exception to this artistic political correctness when working in a studio or painting work for an exhibition: within a formalized aesthetic space or an online forum, your audience actively seeks you out whereas in the case of public art they involuntarily interact with it. “An exhibition is quite different. I can be really acid in my work. But I won’t do it outside because I’m not there to abuse someone or make someone feel bad,” notes Christian.

He emphasizes the contextual, interactive and performative elements of public art and the fact that it cannot exist in isolation. Often in a neighbourhood, the first piece is the deal breaker – if it is welcomed, it creates a positive chain reaction and people become receptive to it.Christian remains pleasantly surprised by the feedback and warmth the genre has received over his past few days of painting in pockets of Colombo. He soon found himself with a bevy of enthusiastic volunteers helping him carry his spray cans and stencils and being invited into the privacy of people’s homes, sharing family stories and food: “In UK I get good feedback but people do not say ‘hey, come on – paint in my dining room’. It is not so quick and so warm.” Usually bringing to the surface what most societies try and sweep under the carpet, he adds: “I think that the little streets I have been painting in are not the streets you put on the tourist guides.” With plans to paint in Slave Island and Galle, Christian’s visit to Sri Lanka is at the invitation of the Alliance Francaise and the Goethe Institute for an art residency.

Equipped with two masters in art and history and influenced by classical artists such as Caravaggio as well as the French Romantics, a mix of theory and history is often infused into his work.Each stencil blends classical and contemporary as well as painstaking detail and the spontaneity and creative chaos of street art. For the most part, Christian tries to do site-specific, thematic work which involves multiple visits to the same location, taking portraits of people, printing it, embarking on the long process of converting it to a stencil (carefully cut by hand) and then returning to paint the final product. With more commissions and more projects, the time to prepare stencils gets shorter and shorter and Christian often dips into his vast library of stencils, adapting it according to each location.

Although often hailed as France’s answer to Banksy, Christian shrugs off this label saying that the mood and tone set in both bodies of works are worlds apart. One displays a provocative, cynical humour while the other stems from a sense of modern humanism. “The big difference is a cultural difference,” observes Christian, saying that a lot of compelling work which has global appeal stems from strong local roots.