Sunday Times 2

The Congress of Vienna revisited

PARIS – Two hundred years ago, on September 25, 1814, Russia’s Czar Alexander I and Friedrich Wilhelm III, the King of Prussia, were greeted at the gates of Vienna by Austria’s Emperor Franz I. The start of the Congress of Vienna ushered in the longest period of peace Europe had known for centuries. So why has its anniversary all but been ignored?

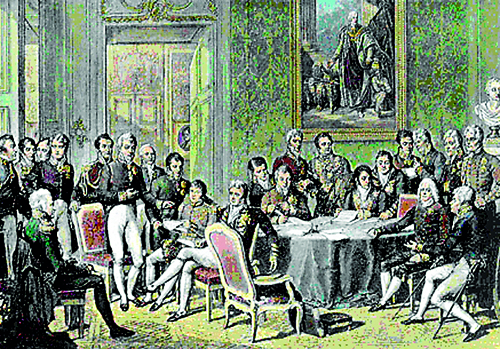

An oil painting depicting the 1815 Vienna Congress that worked out European peace

True, the Congress of Vienna is mostly viewed as marking the victory of Europe’s reactionary forces after the defeat of Napoleon. Yet, given today’s growing global confusion, if not chaos, something like “Proustian” nostalgia for the Congress may not be out of order. Here, after all, was a meeting that, through tough but successful negotiations, reestablished international order after the upheavals caused by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Can we apply any of its lessons today?

To answer that question, we should consider not just the 1815 Treaty of Vienna, but also the 1648 Peace of Westphalia and the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, each of which in its own way brought to an end a bloody chapter in European history.

The treaties signed in 1648 concluded nearly a century of religious warfare by enshrining the principle of cuius regio, eius religio (“whose realm, his religion”). The Congress of Vienna reinstated the principle of the balance of power, based on the belief that all parties shared a common interest transcending their respective ambitions, and re-established the Concert of Nations, which for two generations stopped territorial and ideological revisionism of the type seen from 1789 to 1815. By contrast, the Treaty of Versailles, too harsh to be honoured and too weak to be enforced, paved the way for World War II.

Of the three treaties, the one produced by the Congress of Vienna offers a sort of mirror image to help us understand the specificity of our current conditions. In Vienna, the European powers were among themselves. Their feeling of belonging to a great and unified family was reinforced by the common aristocratic origins of their diplomats. The cultural “other” was not an issue.

Of course, the ambition today cannot be to recreate that world (or to reestablish an anachronistic Westphalian order of religious separation), but rather to devise a new order predicated on different assumptions. Indeed, one of the keys to our current global disorder is that, in contrast to the Congress of Vienna – or, for that matter, the parties of 1648 – the international system’s main actors are not united by a common will to defend the status quo.

The main actors fall into three categories: open revisionists, like Russia and the Islamic State; those ready to fight to protect a minimum of order, such as the United States, France, and Great Britain; and ambivalent states – including key regional players in the Middle East, such as Turkey and Iran – whose actions fail to match their rhetoric.

In such a divided context, the alliance of “moderates” created by US President Barack Obama to defeat the Islamic State – a group that includes Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates – is weak at best. A multicultural coalition is probably a requirement of legitimate military action in the Middle East; the dilemma is that unless Obama’s regional coalition broadens considerably, his current allies’ enthusiasm for US military intervention is likely to diminish quickly.

Or perhaps something like the “bipolar hegemony” of Great Britain and Russia after 1815 (though other players like Austria, Prussia, and France mattered) could be reconstituted, with the US and China substituting for Great Britain and Russia. This seems to be Henry Kissinger’s ultimate dream — a dream that one can glimpse in his latest book, Germanically entitled World Order: Reflections on the Character of Nations and the Course of History.

But can we depend on that dream’s realisation? At a time when we are confronted by Russian expansionism and the extremism of messianic thugs, the lessons from the Congress of Vienna may seem distant and irrelevant. Yet one is obvious: States possess common interests that should trump national priorities.

China, India, and Brazil are stakeholders in the world system, which means that they, too, need a minimum of order. But that implies that they also contribute to maintaining it. China’s interests, for example, would be best served not by playing Russia against the US, but by choosing the party of order over the party of disorder.

A gathering of the modern equivalents of Metternich, Castlereagh, Alexander I, and Talleyrand is also a dream: there are none. But, in confronting today’s growing disorder and escalating violence, the leaders we have would do well to draw some inspiration from their forebears, who 200 years ago this week opened the way to nearly a century of peace.

(Dominique Moisi, a professor at L’Institut d’études politiques de Paris (Sciences Po), is Senior Adviser at The French Institute for International Affairs (IFRI). He is currently a visiting professor at King’s College London.)

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2014. Exclusive to the Sunday Times

www.project-syndicate.org