Sunday Times 2

The Gaza Strip

Gaza on fire; Gaza at breaking point; Gaza fighting intensifies; Gaza truce holding, but . . . Until the ceasefire, the world media were focused squarely for weeks on that 51-kilometre stretch of tension and suspense known as the Gaza Strip, along the Mediterranean’s southeastern edge. Edgy is how things have been over there for decades, the prevailing quiet being no assurance that the Strip will not erupt any time soon and scorch the front pages all over again.

The Gaza Strip being bombed by Israeli Air Force in August. AFP

For many of us, the Gaza Strip registered as an attention-grabbing territorial entity during the Six-Day War of June 1967. That was the week Israel flattened its enemies, stunned the world, and changed the map of the Middle East. The talk then and for a long time after was Israel, its victory, and its spoils of war – the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, the West Bank, the Sinai Peninsula.

Israel’s new land acquisitions gleamed like silver and gold rings plucked off the fingers of the vanquished. Of these engirdling rings, that of the Gaza Strip stood out, for some reason. It might have been the effect of the word ‘Gaza’s’ centrally positioned letter Z, which had a gleam to it, like that of an inset precious stone.

Gaza flashed and fired our imagination

That week in June 1967, and for long after, the 36 voluble teens in our class talked about nothing but Gaza, the West Bank, the Golan Heights. It was as if we were planning a reconnaissance tour of the war zone. GCE Ordinary Level concerns were brushed aside to make way for the extraordinary developments north of Suez.

How familiar Gaza was to us before that dramatic week is hard to say. Looking up the Biblical Atlas in the Religion Class, we might have grazed Gaza with an exploring finger; the novel “Eyeless in Gaza” was waiting on the school library shelf for the day we would embrace Aldous Huxley. But it was the Six-Day War that lodged Gaza firmly in our heads. Like a piece of shrapnel.

Poster of the film "Exodus"

The loaded historical significance of Gaza, one of the world’s oldest cities, we would appreciate only much later; how Gaza went back 4,000 years, and how it had involved three of the world’s great religions, drawn the region’s historic peoples – Egyptian, Philistine, Assyrian, Israeli, Arab, Greek, Roman, Byzantine – and had attracted great individual players such as Alexander the Great and Saladin.

The Six-Day Phenomenon aroused mixed feelings in us schoolboys. Of our 36 classmates, 17 were Muslim and 11 Christian. The Muslims of Arab or Moorish descent were downcast for days. The Christians, including a couple of Roman Catholics, were confused, unsure how to respond to the distant war and its outcome. Whose side do you take in a conflict that does not strictly concern you? Must one take sides? As with sports, it is hard to watch adversaries battling it out and not, even subliminally, root for one side. Do Christians side with Jews when Jews are at war? Tough question – one to take home.

When you are a young teen, parental opinion, wrong-headed or not, outweighs all other opinion. We asked Father what side he was on in the Six-Day War. “Neither,” was his flat, disinterested reply. The tone of his answer, the expression on his face, suggested that the distant warring parties had no claim on his sympathy.

In our classroom breakdown according to ethnicity, we did not mention that there was also a Jewish quotient, a demographic rarity in this country.

The Jewish factor was small, amounting to 2.5 out of 36, or 6.9 per cent. One classmate was the son of a German-Jewish mother who had escaped the concentration camp where her parents were killed; she went to England and later married a Sri Lankan Buddhist, a medical doctor. Two others, Dan Beit-Halami and Ran Peri, were sons of Israeli diplomats based in Colombo. They were both well-behaved, soft-spoken lads. At first, we thought they were brothers. They were both good-looking, had piercingly blue eyes, were fair and freckled, and wore immaculate white  shirts and very short ash-grey shorts. Dan Beit-Halami walked on crutches. A scary scar, the result of a car accident in Israel, ran down his right leg – a flesh-pink ladder of stitches that stopped at the knee joint. You couldn’t meet Dan without being distracted by his formidable scar.

shirts and very short ash-grey shorts. Dan Beit-Halami walked on crutches. A scary scar, the result of a car accident in Israel, ran down his right leg – a flesh-pink ladder of stitches that stopped at the knee joint. You couldn’t meet Dan without being distracted by his formidable scar.

Dan and Ran Peri sat at adjacent desks. Whenever there was a free hour for reading, they would pull out a book from their leather satchels and read – backwards. We were curious not so much about what they read – Israeli fiction and translated European classics such as Balzac’s “Eugenie Grandet” – as their intriguing reading mode. We had already seen this procedure when our Muslim friends opened the Quran.

Dan and Ran Peri would start at “the end”, opening what readers of English books would call the back cover and go from “last” page to “first”, turning pages in “reverse” order. Their books were in Hebrew. The script, like Arabic, was page upon page of decorative code, mysterious and beautiful in its impenetrability.

All of this made Dan and Ran Peri a fascinating presence. Here were friendly aliens who hailed from the Holy Land, had breathed the gritty air blowing over the pages of the Torah and the Old Testament, and had crossed blinding deserts and blue skies to join us in Colombo. They were exotic. They were out-and-out outsiders who fitted in perfectly.

In actuality, years before Dan and Ran Peri’s arrival, there was an opportunity to see the Hebrew script in action. This was a cinema memory from 1959, of Charlton Heston as Moses looking on as the Finger of God traced the Ten Commandments in jabs of laser lightning; the writing started on the right “page” or stone tablet and moved from right to left.

(Reference to the contrary ways of Hebrew and Arabic came up in another film, the 1964 “My Fair Lady”, in which Rex Harrison as Professor Higgins ranted about the world’s languages, singing that “Arabians learn Arabian with the speed of summer lightning, and the Hebrews learn it [Hebrew] backwards, which is absolutely frightening.”)

It has to be said of our Israeli classmates that not once during the Six-Day War did they betray the least excitement, or even interest, in the history-making events taking place in their homeland. Daily that week, while we were full of the news flying out the Middle East, they said nothing. Excited they must have been, but they did not show it. Like their parents, Dan and Ran Peri were diplomats.

Dan and Ran Peri’s presence gave a palpable third dimension to our concept of Israel and Jewishness. They embodied an aspect of the Middle East, historic and modern, and represented an ancient people, persecuted and scarred. Having them in our midst was exciting.

Dan, who had film-star looks, reminded us of yet another, older, film, one that featured Paul Newman and was all about the Jewish people and their search for the Promised Land. (Dan looked a lot like Paul Newman; similar nose, chin and sharp-edged rectangular forehead.)

“Exodus”, screened at the Rio Cinema, Slave Island, in 1960, told a powerful Jewish tale set against the backdrop of the founding of the State of Israel. The plot dealt with the adventure of bringing a ship full of Soviet Jewish refugees safely to Palestine. The story was fiction, but the ship was named after a real vessel called “Exodus 1947″, which was used in an aborted attempt to bring Jewish illegal immigrants to Palestine.Focused as it was on Jewish hope and anguish, “Exodus” was dramatic and deeply moving. It also cast Arabs in the “bad guys” role. The Otto Preminger film came to be labelled “racist” and “Zionist”; in fact, it is claimed that “Exodus”, book and film, left a permanent negative impression of the world Arab community among a generation of Americans, not forgetting the world’s film-goers.

In two easily overlooked footnotes in the 706-page book “1967 – Israel, the War, and the Year That Transformed the Middle East,” Israeli writer Tom Segev says the American Jewish writer Leon Uris was approached by a secret unit of the Israeli government known as Nativ, which persuaded him to write the novel that became the bestselling “Exodus” (1958). The film that followed three years later was produced by United Artists, whose chairman was Arthur Krim, a lawyer-film producer and a prominent member of the politically influential US Jewish community.

A couple of years ago there was a big class reunion in Colombo, and scattered alumni from here and around the world gathered at a five-star hotel. The conversation was naturally about school life in the ’60s. At one table, “Gaza Strip” was mentioned, and there was a splutter of liquor-soaked laughter. Someone then stood up to re-enact an outrageous, oft-recalled classroom episode, which became a classic in our stock of high school high jinks. Suddenly we were back in 1967, not long after the June Six-Day War.

Devashri Abeywansa (not his real name but close) was the class entertainer. A natural actor, his talent was fed by the films he saw, and he saw films daily. He notched up an average seven shows a week, and once took in four movies in a single day, which is to say he saw more films than the rest of the class or school put together. Monday to Friday evenings, while we did our homework, Devashri did the cinema circuit.

In his precocious dedication to the motion picture industry, Devashri was aided and abetted by an adoring, spoiling mother who herself loved the movies, and who was, in her glamorous Max-Factored way, as attractive as any Hollywood star.

If he was too young to accompany his mother to Adults Only films, Devashri obtained from her frame-by-frame descriptions of naughty Tinseltown acts and off-limits excitements, such as the “World by Night” series. The next day he would share with us cinema’s risky, forbidden thrills. Suiting action to word, he gave us the Striptease, as performed in the world’s sin capitals, from Las Vegas to New York to Paris to Tokyo.

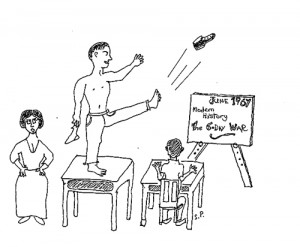

One memorable afternoon in ’67, while the Six-Day War was still news, the class requested a striptease from Devashri to liven up an empty hour when the Maths teacher had failed to appear.

Ever the ready entertainer, Devashri hopped on to his chair and, to the beat of 35 pairs of hands rhythmically striking 35 desks, he started to “strip” in classic Hollywood burlesque style. It helped, in his evocation of Western decadence, that Devashri was a startling throwback to his Scottish planter grandfather: he was fair of skin, fair as Marilyn Monroe. Fairer.

Slowly that hot humid afternoon he undid his white shirt, one teasing button at a time; then, shrugging à la Jayne Mansfield, he coyly winked over a naked white shoulder; next, he peeled off his shirt and tossed it into the middle of the room. Someone grabbed the sweaty item, rolled it into a ball, kissed it and tossed it in the air. The beat grew louder. Devashri hopped on to his desk and from this outrageous perch, as if standing in high heels and fishnet stockings, started to remove his shoes.

Twirling a scuffed Bata shoe on one finger, he slipped off a wet white sock and let it drop. Loud cheer. He started swinging his other shod leg until the second shoe shook loose. Louder cheer. With one final swing, the beat now thunderous, Devashri sent the second shoe flying. The black object described a parabola that curved up to the ceiling and landed with a thump on someone’s desk.

There was a raunchy schoolboy roar.

Then silence.

It was as if the soundtrack had been unplugged.

Standing in the doorway, hands on hips, was the Maths Teacher.

Madame, as she was called, strode into the classroom. She was not a tall woman, but on that occasion she was towering in her rage. Her glasses glittering, she told the semi-naked Devashri: “Abeywansa, you can dance with all the women in the street, but you cannot dance with me. Come right here, Mister, and explain yourself.”

Forty-seven years makes for ancient history, but time has not dulled the brilliance of that spectacular show of schoolboy gall. In the class of 36, the persons most amused were our good friends from Israel, Ran Peri and Dan Beit-Halami.

The Gaza Strip”, as it came to be called, became a party favourite.

If the above set of connected true episodes has any other theme besides the fallout from West-Asian vexations and Middle-East meddling and muddling, it is the fact of our debt to cinema – cinema’s power to transport us to anywhere, implant memories, flood the mind with colours and causes, manipulate thought, but above all to entertain.