Understanding liver transplantation

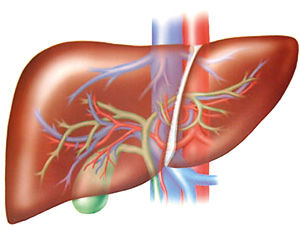

View(s):A liver transplant involves removing the patient’s own diseased (“native”) liver at surgery and replacing it with a liver from another person. This is commonly referred to in medical literature as Orthotopic Liver Transplant (OLT). Generally, the patient (“recipient”) receives a whole liver but on occasion may receive only a portion of the donor liver.

Liver transplantation is indicated in children and adults, whose livers are failing due to liver disease, have primary liver tumours, or systemic diseases where liver replacement will be potentially curative. The causes of liver failure vary by the patient’s age group. In children, a common reason for liver transplantation is biliary atresia, a disease in which the bile ducts, which are the plumbing system of the liver, do not develop properly.

Liver transplantation is indicated in children and adults, whose livers are failing due to liver disease, have primary liver tumours, or systemic diseases where liver replacement will be potentially curative. The causes of liver failure vary by the patient’s age group. In children, a common reason for liver transplantation is biliary atresia, a disease in which the bile ducts, which are the plumbing system of the liver, do not develop properly.

In adults, frequent causes of liver disease leading to the need for liver transplantation include alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus, Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatoblastoma (in children) and hepatocelllular carcinoma (in adults) are two important tumours where liver transplantation may be indicated if surgical removal of the affected part of the liver is not feasible.

An uncommon but important indication for liver transplantation is acute (“fulminant”) liver failure in which a person with no previous history of liver disease rapidly goes into liver failure. Important causes of this condition include drug overdose (either accidental or suicidal), from medications such as paracetamol, or acute viral hepatitis A or B.

Does every patient with cirrhosis need a liver transplant?

Fortunately, many patients with cirrhosis remain stable (“compensated”) for years. Symptoms such as fluid retention in the abdomen (“ascites”), confusion (“hepatic encephalopathy”) or more dramatic problems such as bleeding from large veins (“varices”) in the esophagus or stomach are major events that indicate the liver condition is deteriorating and that referral for liver transplant evaluation is required.

Another important indication for liver transplantation is the discovery of a tumour in the liver of a patient with cirrhosis. In adults, most patients with hepatocellular carcinoma have cirrhosis and thus an important part of the management of patients with cirrhosis is screening for tumours at an early stage as they may do well with resection of the tumour surgically, ablation by injecting the tumour with alcohol, radiofrequency ablation or possibly liver transplantation. Careful and regular follow-up (at least twice a year) with a physician experienced in the management of liver disease is key to look for these complications and monitor the patient’s liver function on a regular basis.

Another important indication for liver transplantation is the discovery of a tumour in the liver of a patient with cirrhosis. In adults, most patients with hepatocellular carcinoma have cirrhosis and thus an important part of the management of patients with cirrhosis is screening for tumours at an early stage as they may do well with resection of the tumour surgically, ablation by injecting the tumour with alcohol, radiofrequency ablation or possibly liver transplantation. Careful and regular follow-up (at least twice a year) with a physician experienced in the management of liver disease is key to look for these complications and monitor the patient’s liver function on a regular basis.

Preperation

When a patient is seen at a liver transplant centre, they undergo a rigorous evaluation to assess not only how severe their liver disease is, but also whether they have any other medical conditions which might impact their ability to undergo this major surgery. If the patient has a prior history of drug or alcohol problems, a plan needs to be in place prior to transplant to avoid relapse afterwards.

Additional workup usually involves x-rays of the liver and adjacent organs, some form of cardiac stress test, a number of blood tests including blood group, hepatitis markers and an HIV test, and additional medical consultations.

What are the contraindications?

Liver transplantation may not be possible in some patients because of other severe medical problems such bad heart or lung disease which would make the surgery very risky and the chance of a good long-term outcome unlikely. Extensive liver cancer would also reduce the chance for a good long-term outcome and thus transplant is not performed in this situation.

Some primary liver tumours such as cholangiocarcinoma which grows from the bile ducts do poorly with liver transplant based on a high rate of tumour recurrence after an otherwise successful operation. However, good results have been achieved within protocols conducted at selected centres which combine radiation therapy with transplant for cholangiocarcinoma in highly selected patients. Similarly infection with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS was regarded as a complete contraindication to any form of transplantation prior to the introduction of Highly Effective Antiretroviral Therapy in the mid-1990s. Now, carefully selected HIV infected patients without AIDS are accepted by some programmes for liver transplantation. Finally, a number of patients with severe obesity may not be candidates for liver transplantation based on the difficulty in performing the surgery and the potential for reduced long-term success rates.

Where do donor organs come from?

Donated livers come from living and non-living donors. Living donors donate a part of their liver. The donated and the remaining part of the donor’s liver will grow to the size the body needs in weeks. Deceased donors are individuals who have suffered brain death following a massive brain injury such as severe head trauma or major stroke, which means that even though many of their bodily functions continue, they have no prospect of returning to consciousness. A careful examination by an experienced brain specialist with appropriate x-rays and other investigations such as testing for brain waves is needed to confirm the diagnosis of brain death. The organs to be used for transplantation into the recipient or recipients are removed (“procured”) by a team of surgeons and then taken on ice in a special preservative solution to the centre where the recipient is waiting. Several different recipients may receive organs from the same donor (i.e. kidneys, heart, lungs and liver).

Another approach is for a healthy adult to donate a portion of his/her liver for either another adult or a child. The amount of donor liver necessary for the surgery depends on the size of the potential recipient with a fully grown adult requiring the largest amount (usually most of the right liver lobe).

The donor operation is very complex in live donor transplant as not only must the portion of the liver removed have intact blood vessels and bile ducts, but the part left behind must function well enough so that the donor will not develop liver failure. Generally, living donors are relatives or have some other significant relationship with the potential recipient, have the same blood type, are in excellent general health, and have liver anatomy that will allow safe removal of part of their liver.

What does the surgery involve?

Liver transplant surgery is very complicated in large part because the diseased native liver can be very difficult to remove from the recipient. Once this is accomplished, however, the donor liver is placed in the recipient’s abdomen. The major blood vessels are reconnected in the new liver as well as the bile ducts. Anti-rejection medications are started in the operating room and the patient is then transferred to ICU for careful monitoring. Typically, patients are transferred out to a regular floor within a few days. During this time, the correct dose of anti-rejection medications is established. Patients are usually discharged from hospital within two to three weeks of the transplant.

What does the long-term follow-up after liver transplant involve?

Patients are seen frequently in the first weeks and months following transplant. Key aspects of care include confirmation of wound healing, removal of sutures, and regular blood tests including liver function tests (LFTs) and creatinine to monitor kidney function which can be affected by the anti-rejection medications. If the LFTs become abnormal, further investigation with a liver biopsy (to rule out rejection) and/or endoscopic cholangiography (to rule out bile duct obstruction) may be necessary.

Most patients return to a regular lifestyle six months to a year after a successful liver transplant. Eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and taking recommended medications are important factors to staying healthy. Nearly 75% of liver transplant patients are alive five years after their transplants.