Driven to tell stories of the forgotten Boer POWs

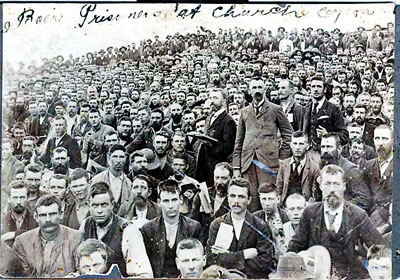

The Boer POWs seen in a postcard

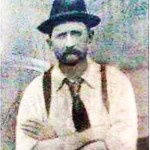

‘The last irreconcilable’ as he was known, Henry Engelbrecht, the first game warden of Sri Lanka’s most famous national park was a Boer Prisoner of War who tended the sanctuary for 21 long years with great devotion. It was in search of the camps where he and some 5,000 others like him who had been shipped here from South Africa had been interned that Britisher Robin Woodruff first came to Sri Lanka four years ago.

The Boers (Afrikaners) are descendants of the Dutch, German and Swedish settlers of South Africa sent there by the Dutch East Indies Company in the 1600s and French Huguenot refugees. The conflicts that arose after the British colonised the Cape sparked the Boer War of 1899-1902.

Robin Woodruff hadn’t heard of the Boer War until 2006 and knew nothing of St. Helena, a remote island in the South Atlantic or Ceylon where Boer Prisoners of War (POWs) were interned at the beginning of the 20th Century. But a fascination that began with an intricately carved walking stick made by a Boer POW has now led him to spend all his spare time in pursuit of this chequered period of Boer history.

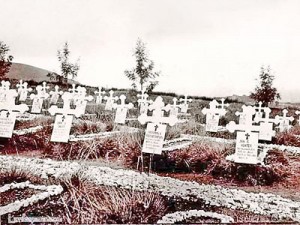

the graveyard at Diyatalawa as it was

So it was that over the New Year of 2010, his research brought him to Sri Lanka, (he has been four times in the past four years) and to the home of Deloraine Brohier, daughter of renowned historian and scholar Dr. R.L. Brohier, who had written extensively on the Boers. Deloraine promptly got him access to the most well-known Boer POW camp at Diyatalawa, (the site is now under the military and the Surveyor General’s Department) where over a century ago, a large enclosure had housed hundreds of prisoners. There were other Boer POW camps too – at Mount Lavinia (where the convalescents were sent), Ragama (for dissidents) and at Hambantota and Urugasmanhandiya (for prisoners on parole). All in all, there were around 5,500 Boer POWs dispatched to Ceylon.

‘The town of Silver Sheen’ as the Diyatalawa POW camp was known for its rows upon rows of huts made of corrugated iron is no more. What Woodruff saw was many huts painted dark green. He notes with some regret that there is nothing left of the Boer graveyard on Boer Road, which is today a rifle range for the services. The graveyard had 133 graves of Boer POWs, each marked with a wooden Celtic cross, the work of an unknown carver and five graves with marble and stone monuments. Today all that stands is a cairn built in 1918 with the inscription ‘In memory of the Prisoners of War who died at Diyatalawa Camp who were buried near this stone. Erected by the Government of United South Africa, 1918’.

Engelbrecht’s descendants: Lankan granddaughter and South African great great granddaughter

R.L. Brohier captured a different, more tranquil scene in 1940 when he wrote:“as one passes out of this well-ordered sanctuary, far away from the hustle and bustle of urban activity, who will gainsay that it is better that these Boers should lie here, amidst lemon-scented grasses which scatter their fragrance when the tussocks wave in the wind, than in the congested environs of a city. They were accustomed to the silence of vast spaces.”

Woodruff had read extensively Richard Stroud’s “Ceylon, the Camps for Boer Prisoners of War 1900 -1902” and also R.L. Brohier’s ‘Seeing Ceylon’ where he mentions “Prisoner No. 9607 Henry Engelbrecht, age 32 from Strydfontein, in the district of Bethulie was captured at Fouriesberg on the 19th of June 1900 while serving with the Groot Rivier Cornetcy and was sent to Ceylon on the Bavarian”.

Engelbrecht was called the ‘last irreconcilable’ because he refused to take the oath of allegiance to the British sovereign, after the war ended and hence was not shipped back home to South Africa like his more amenable compatriots. “There were about 20 irreconcilables, then the number came down to five and finally down to two,” Woodruff says, adding that he was able to meet the great grand-daughters of them both.

Deloraine had shown him a picture of Engelbrecht’s grave in the Catholic churchyard in Hambantota and so they headed there from Diyatalawa.Letting them into the graveyard, Fr. Prasanna Rodrigo, OMI warned Woodruff that the tsunami had destroyed many graves but his eye almost immediately fell on the distinctive pointed tombstone, just 15 to 20 feet away. It was covered with weeds, dirt and grime but was

Henry Engelbrecht

unmistakably the grave he was looking for.

The inscription was indecipherable. He wanted nothing more than to clean it then and there but night was closing in and so the next morning armed with a bucket, scrubbing brush and cleaning materials, they began work, joined by a few curious onlookers.

All the diligent scrubbing paid off: A light application of chalk and the words inscribed emerged:

“In memory of H.E. Engelbrecht, Died 25th March 1928 For 21 years the guardian of the Yala Game Sanctuary

This stone is erected by members of the Ceylon Game Protection Society in appreciation on of his work and great knowledge of the jungle”.

Woodruff’s research also led him to the Lankapura website and once he had posted news of his interest in all things Boer, people began writing in, some looking for family connections and others volunteering information about their ancestors.

One query had him greatly excited. It was from Yolande, living just outside Johannesburg who was looking for her great-great-grandfather Henry

Robin Woodruff

Engelbrecht. As fate would have it, she was coming to India on a conference. “Why not sidetrack and come here?” I told her,” Woodruff says. He picked her up at the airport at 4 a.m., and they went straight to Diyatalawa and then down to Hambantota. It was then that Lionel the driver, to their surprise, volunteered that the man who was going to take them around the Yala park, knew some of Engelbrecht’s relatives.

Henry Engelbrecht’s son Harry had also been a ranger in the park and they were told his daughter was living in Hambantota. When they sought out the 80-year-old, she welcomed them to her humble home and proudly showed them a book written about her grandfather and her birth certificate with the Engelbrecht name. “Yolande was fascinated to find that she had relatives here,” Woodruff says, adding that there was another elder daughter too, who he had heard had since passed away.

Such discoveries and fortuitous meetings have only strengthened Woodruff’s resolve to learn more about the Boer history in this country and led him to make more visits, like his most recent in August this year.

What has now grown into a seemingly unending quest, curiously enough, all began back home in England with a walking stick, Woodruff says. A walking stick with the handle delicately wrought in the shape of a duck’s head which came into his hands in 2006. It bore the inscription – “Made by a prisoner of the Boer War, St. Helena, 1900”.

His grave in Hambantota

Woodruff had over the years been picking up walking sticks, and had in his collection one dating from 1682 and even one belonging to King George V. But this was different. He could recognise a work of art, for that it was.

Two more walking sticks, one from Bermuda and the other from Ceylon both made by Boer POWs then came his way and reading a book about the Boer War collectibles, he realised that it was not just walking sticks, but an array of handicrafts that the prisoners had made in captivity: Furniture, jewellery boxes, pen stands, paper knives, candle stands, serviette rings, even chess boards.

R. L Brohier in his work ‘The Boer POW in Ceylon’ described their work thus: “not having the tools, they devised planes out of table-knives, saws out of barrel-hoops and, with the aid of these and other improvised implements, turned out souvenirs and multitudinous articles of utility, most of them from waste material.”

Not even ten years later, though busy with his regular job in the airline print trade, Woodruff’s deep engagement with Boer POW history has led him not only to Sri Lanka but also St. Helena and Bermuda. The first Boer POW contingent was sent to St. Helena on April 11, 1900, he says, explaining how interestingly, many, incarcerated at the two camps on the island, Broadbottom and Deadwood, were Freemasons. There were also more than a dozen Boer POW camps in India, several in Bermuda, and as we know, in Ceylon.

If Sri Lanka was easy to visit, not so St. Helena. Travel to this rocky island is possible only by ship – the RMS Helena, the Royal Mail delivery boat – a five-day voyage. “You haven’t seen anything for five days, you don’t see a bird, you don’t see a ship, then there’s this big black rock just sticking out of the ocean. The ship has to dock outside because the harbour is shallow and you go in by small boats,” he says. Napoleon Bonaparte’s grave was also on St. Helena, he adds, till it was moved to Paris.

Driven now by a need to tell the stories of the long forgotten POWs and their skilled handicrafts, Woodruff is working on his own book ‘Captivated Carvings – Stories of Boer POWs and their Art’ and will be back here, he says, for there is so much more to uncover.