Sunday Times 2

Lankan fishers entangled by global powers

On Oct 20th hundreds of angry southern fishers protested opposite the Fisheries Ministry in Colombo against a European Union ban on seafood exports from Sri Lanka and the Government’s promotion of joint ventures with East Asian fishing companies. Over the years, there have been numerous protests by northern fishers against poaching by Indian trawlers. These protests are a reflection of a larger crisis in Sri Lankan fisheries; the fishers face dispossession and fear the end of their way of life.

The fisheries sector contributed 1.3% to GDP and 2.4% of total exports in 2013. Furthermore, over 12% of the total population (2.4 out of 20 million) is dependent on the fisheries; in the Northern Province this is even as high as 20%. Sri Lankans on average eat 24kg of fish per year, which constitutes 55% of all animal protein intake, one of the highest in the world. What is more, the cheaper varieties of fish are available for as little as LKR 80/kg (INR 40/kg) providing vital food security for the poor.

Livelihoods and the Palk bay conflict

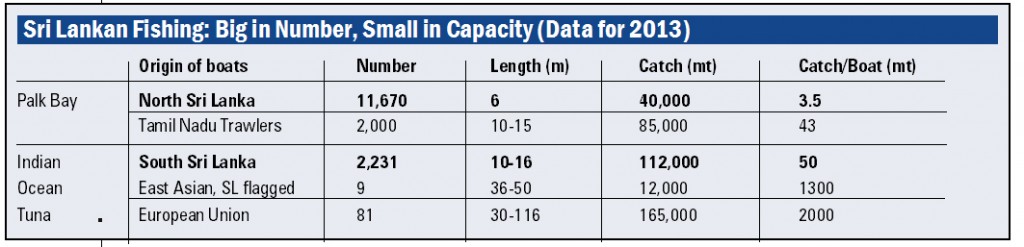

Fisheries in the North recovering from the devastating war are crippled by the persistent poaching of trawlers from Tamil Nadu. Of the 7500 trawlers in Tamil Nadu, 2000 are fully or partly dependent on Sri Lankan waters for making ends meet. In Tamil Nadu, fishers and politicians have framed this issue as one of bona-fide fishers hammered by the Sri Lankan Navy. Furthermore, the root cause has been popularly attributed to Indira Gandhi ‘giving away’ traditional fishing grounds including Kachchatheevu to Sri Lanka in 1974. In reality, to secure a profitable catch, Indian trawlers move deep into Sri Lanka’s northern and eastern coastline.

In 2013, out of 45,167 reported sightings of Indian trawlers in Sri Lankan waters by its Navy, only 180 boats with 730 Indian fishermen were arrested. On average, these fishermen were kept in Sri Lankan custody for 29 days. Northern fishers in Sri Lanka are desperate and are appreciative of the stronger stand, particularly the confiscation of Indian trawlers.

Over the years, Indian trawlers have damaged the expensive nets resulting in increased indebtedness of northern fishers. And now, on the three days of the week when Indian trawlers venture into their waters, northern fishers either stay home or go for smaller near-shore fishing. The result is a substantial loss of income. In 2013, the average fishing income of a household in the village of Karainagar in Jaffna District was LKR 14,700, which is a third of the average rural household income in Sri Lanka.

Sadly, the Palk bay fishing conflict has become entangled in polarised politics, without a solution for fishers’ livelihoods and Tamil Nadu’s overcapitalized trawler fleet.

EU ban and the laws of the seas

The southern fishers of Sri Lanka involved in deep-sea fishing were relatively unhindered except for occasional arrests in the Indian waters. This deep sea fishing fleet is world famous for the relatively small 10-16 meter vessels packed with water, ice and rations, making journeys lasting weeks and traveling thousands of kilometres into the Indian Ocean in search for tuna and shark.

In a shocking development, on Oct 14th the EU announced a ban on Sri Lankan seafood imports from 15th January 2015. This is likely to have severe economic consequences for southern fishers, as 70% of Sri Lanka’s fisheries exports are to Europe. The EU argues that Sri Lanka has failed to cooperate in eliminating illegal, unregistered and unregulated (IUU) fishing. According to newspaper reports, the straw that broke the camel’s back and led to the ‘red card’, has been the sighting of Sri Lankan flagged fishing boats in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Diego Garcia, a ‘British Indian Ocean Territory’.

In a shocking development, on Oct 14th the EU announced a ban on Sri Lankan seafood imports from 15th January 2015. This is likely to have severe economic consequences for southern fishers, as 70% of Sri Lanka’s fisheries exports are to Europe. The EU argues that Sri Lanka has failed to cooperate in eliminating illegal, unregistered and unregulated (IUU) fishing. According to newspaper reports, the straw that broke the camel’s back and led to the ‘red card’, has been the sighting of Sri Lankan flagged fishing boats in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Diego Garcia, a ‘British Indian Ocean Territory’.

What led to this development? One factor has been Sri Lanka’s questionable allocation of licences to relatively large East Asian fishing vessels. These joint ventures are linked to the over ambitious targets for increased fish production, inspired by Sri Lanka’s post-war high growth development regime.

In 2009, the fisheries development strategy plan announced that off-shore fish production had to be tripled from 113 to 332 thousand metric tons by 2013. In May 2013, Fisheries Minister Senaratne stated plans to increase fisheries exports from US$ 250 million in 2012 to US$ 500 million by 2015, through joint ventures with major Chinese and Japanese fishing companies.

Sri Lankan boats are regularly sighted in foreign waters, going against the EU mantra of regulated and traceable fishing. But it is the Sri Lankan flagged multinational vessels that were reported to the EU for illegal fishing in Diego Garcia.

Yet, this ban is fishy! The Indian Ocean Tuna Commission database reveals the following declining order of largest tuna harvesting states in the Indian Ocean: Indonesia, the European Union, Iran, Sri Lanka, Maldives and India. In 2013, Sri Lanka’s fleet of 2230 boats caught 10%, while the EU caught 16% of total tuna landings from the Indian Ocean. The EU fleet consists of 81 industrial vessels with an average capacity 50 times that of one Sri Lankan vessel. The contribution of this European fleet to employment and food security is not only nil to the people of the Indian Ocean, but also marginal to Europeans themselves.

How have European fleets ended up in the distant Indian Ocean? And how can the EU reprimand Sri Lanka for fishing near Diego Garcia?

At the root of this is the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a treaty which added 200 nautical miles (360km) territorial extension called the ‘Exclusive Economic Zone’ (EEZ) to nations’ territorial waters, providing exclusive resource exploitation rights. Overnight, the small but strategic colonial islands occupied by European countries gained immense economic significance.

Thus in 1982 the UK gained exclusive exploitation rights over 639,000 square kilometres of seas around Diego Garcia, a barren archipelago used as a US military base. Since then, a Sri Lankan or Indian fishing boat in these waters became a poacher subject to punishment by the EU.

Seen from this historical perspective, banning Sri Lanka’s tuna exports in the name of sustainability and non-compliance is both paternalistic and hypocritical. In Sri Lanka, officials and fishermen alike have been wondering why the EU hasn’t applied the same IUU sanctions in relation to Tamil Nadu’s intense poaching in Sri Lankan waters.

The logic of states, law and development

There is no doubt that fisheries require some form of regulation. Fisher folk have developed fishing practices and customary laws to manage their affairs over centuries. However, in this day, international law, science based management, ideas about state sovereignty and territory, and grand development visions are increasingly determining fisheries policies. This is the context for the debates and legalistic assertions on “Kachchatheevu” and the EEZ of Diego Garcia.

Fishers’ concerns have also become pawns in the geopolitical game of state interests. With dialogue between fishers from both sides of the Palk Bay deadlocked, the two governments are now driving negotiations. Significantly, President Rajapaksa ordered the release of all Indian fishermen in custody, immediately after India abstained from backing a UN human rights resolution against Sri Lanka early this year. Similarly, southern fishers may face new rules negotiated between their Government and the EU that may aggravate ground realities. Few decades back, it was the Indo-Norwegian statist modernisation vision that led to the introduction of the ecologically devastating practice of bottom trawling in India.

The encroachment of Indian trawlers, the joint ventures with East Asian vessels as part of Sri Lanka’s development push and the interference of the EU have a common impact. They cripple small-scale fishers who are powerless in the face of decisions taken at the level of states and international forums.

The development argument in Sri Lanka, that supporting technologically ‘inefficient’ small-scale fisheries is economically unrealistic and naïve, does not hold. The alternatives for men and women from the fishing community have been either migrant work in the Middle East and countries such as Italy, or work in the garment factories in the Free Trade Zones. Both options consist of temporary migration uprooted from their communities and families, comprising mainly unskilled precarious work. Compared to these options, small scale fisheries continue to have potential for decent livelihoods with dignity, provided trans-national and mega development driven dispossession is kept at bay.

Joeri Scholtens is a researcher at the Centre for Maritime Research, University of Amsterdam (Netherlands). Ahilan Kadirgamar is a researcher and political economist based in Jaffna (Sri Lanka).