Sunday Times 2

Face to face with a man-eating tiger

Nothing strikes more fear into the hearts and minds of the people of the Sundarbans – the vast river delta on the northern shore of the Bay of Bengal – than the word “tiger”. Even the mention of this word can send villagers into a blind panic.

Eager to catch a glimpse of a tiger, I asked a passing fisherman if he had seen one on his travels that morning. Up to that point he had been happy to pass time with me – but immediately he packed up his crabs and left without a word.

“If you talk about the tiger, it will come,” said my boatman. “That is why.”

A male tiger is released into the waters of the river Harikhali at the Sundarbans delta forest (Reuters)

There is hardly a person here whose life hasn’t been touched by a tiger in some way.

Some areas are more prone to attacks than others. Between 2006 and 2008 several people were killed in Joymoni, a small village on the banks of the Pashur river, bordering the forest. In one of the attacks, a tiger burst through the bamboo walls of a hut in the middle of the night, and snatched an 83-year-old woman. Her son, Krisnopodo Mondol, who was in his late 60s at the time, heard her screams.

“I opened the door and ran to my mother’s bed. But my mother was not there,” he says. “All I saw was the empty bed. I couldn’t find her anywhere. I opened the door to the veranda and in the moonlight I saw my mother. She was badly injured lying on the ground, her clothes strewn around her.”

Tears stream down Krisnopodo’s face. At one point he is so overcome with grief, he can’t talk. He fetches a picture of his mother from the wall and looks at it with disbelief. Then he continues.

“The tiger attacked my mother in the left side of her head. Her skull was broken. She was still breathing but senseless.” Before long, she died.

“On my deathbed, I’ll still remember my mother that night,” Krisnopodo says. “When I recall that accident, I cannot hold back my tears. I can still hear that sad scream.”

Shortly after the attack, Krisnopodo and his wife moved to a concrete house a short distance away from Joymoni, where he now makes a living by drying coconut in his garden, fenced off from the world.

Most people in the Sundarbans rely on the forest and the river for food and earn money by collecting wild honey and fishing. Although it’s illegal, many go into protected areas – the Sundarbans is a Unesco World Heritage site – to cut firewood and poach animals, and it’s this that brings them into direct conflict with the tiger. This summer two people were killed in separate incidents while fishing for crabs.

In 1997, Jamal Mohumad went into the forest to hunt and fish for food – and found himself in competition with a bigger and more ferocious hunter.

A paw mark of a tiger cub is seen on the fringes of a forest in the core area of Sundarbans Tiger Reserve (Reuters)

“The tiger lunged at me with its paws. It dug its claws into my legs and dragged me under the water. I struggled under the water and dived down about 10 feet under the water. The tiger let go of me. I swam deep under water as fast as I could. After a while, when I reached the surface of the water, I couldn’t see the tiger. I swam down the river for a bit and saw a boat and cried out for help.”

Jamal is a local legend in the Sundarbans. He’s the only person anyone knows who’s survived three separate tiger attacks.

In the most recent, in 2007, he’d gone to the forest looking for firewood, when, in the tall grass by the side of the river, he spotted a tiger lying in sun.

“The tiger was on the north side of the river and I was on the south side. I couldn’t run. I knew if the tiger saw me he would attack so I said a prayer.”

The tiger stalked Jamal. Frozen, Jamal stood his ground. He knew that if he turned to run he would be done for.

“Because I had been attacked twice before I was more conscious about what to do. So I stood in front of the tiger and made mad faces at it and lots of noise.

“The tiger also fears humans, you know. Both can attack each other and it is dangerous for both parties.”

The tiger came to within a metre of where Jamal was standing and let out a huge roar. Jamal roared back.

“I roared and roared at the tiger and made the scariest faces I could. It went on for about half an hour until my throat was bleeding.”

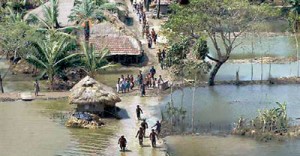

Patharpatima Island in the Sundarbans delta. The Sundarbans, a mangrove forest at the edge of the Bay of Bengal, stretch across parts of southwestern Bangladesh and southeastern India (Reuters)

Jamal’s wife heard the noise and fetched a crowd from the village.

“They made so much noise, they scared the tiger off. When I saw my friends from the village, I collapsed.”

Unlike many villagers who’ve been attacked, Jamal still goes to the forest – but he is more cautious now.

“I always see the tiger in my dreams and when I go into the forest there is a deep fear within me that the tiger is watching me and might attack me again. But I have to go to the forest to ensure foods for my children. It’s only for them that I have to face the tiger again and again.”

The tigers in the Sundarbans appear to be more aggressive than those in other parts of the world. It is not fully understood why this should be – some suggest it might be the high salinity of the water.

But the most likely cause is depletion of their natural habitat and a shortage of prey. With a million people living on the fringes of the mangrove forest, food scarcity is a problem for humans and tigers alike, with each poaching the other’s prey.

In one village studied by conservationists, tigers were found to kill about 80 domestic animals a year – dogs, goats, buffalo and cows. As a result, villagers carried out several attacks on tigers in retribution. To stop this, in 2008 local conservation groups rolled out 49 Tiger Village response teams.

Each team of volunteers is responsible for dealing with tigers that stray into villages. Rather than kill the animal, villagers scare it back into the forest by brandishing flaming torches and setting off firecrackers. If this fails they have a number to call to get a swat team on the ground with a tranquilliser to sedate the tiger so that it can be taken back to the forest.

Nonetheless, retaliatory attacks still happen. In December 2013 a group of villagers living near Ghagra Mari forest station tracked down a tiger and killed it after it had attacked and killed a human.

The idea that tigers might one day become extinct is hard for local people to grasp. A fisherman, Deban Mandal, looks at me suspiciously when I put this to him. “How could such a fierce animal possibly be at risk of dying out?” he asks.

Have I not heard the beating heart of a tiger? I confess I have not. He throws back his head and laughs. “I have heard a tiger’s heart, and it’s stronger than mine.”

Deban was on his way to the Kultoli Khal area of the Sundarbans to fish. The fishermen pulled their boat to the shore shortly before dawn.

The tide was low and they made their way into one of the many muddy rivulets that lead into the forest. Everything was completely silent. Just the sound of their footsteps among the mangrove roots.

Deban went down to the edge of the rivulet and said a prayer. It was just after sunrise and the mist was rising off the still water. Stepping forward into the silky mud he laid down his net. At that moment, from out of nowhere, a tiger flew at him.

“Its roar was so loud it was like a thunder to me,” he says, imitating the sound of the animal.

“I was completely helpless. With the weight of the tiger, I thought I would fall, so I grabbed hold of his torso and laid my head against his chest. I could hear the tiger’s heart thumping so fast. I just clung on with my ear to its chest. I could feel its breath on my head, as it tried to attack me.”

He looks at me, his eyes wide as he recounts the event.

“I thought if I could keep holding on, it would not be able to bite me. But it thrashed from side to side and eventually I toppled over and it bit me here on my neck. I was sure I would not live any more.”

One of the fishermen climbed up a tree, but another came to Deban’s rescue.

“One of the guys came up with an axe or something long, maybe a piece of wood, and hit its head. When it was hit, the tiger released me and ran away.”.He shows me the scars on his neck – I can see clear puncture marks.

“When I see a tiger now, I’m filled with fear. When our boss asks us to visit the other side of the river, I tell him if the tiger sees me, it will certainly catch me. He tells me: ‘Why would it catch you?’ I tell him it secretly watches me from the jungle, I know if I go, it will find me.”

(Courtesy BBC)