Sunday Times 2

The Berlin Wall and the clash of ideology

To mark the 25th anniversary of the fall of the infamous Berlin Wall Ameen Izzadeen’s interviews with three Colombo-based ambassadors was published last Sunday.

While one might contest some of their conclusions, especially the denial that they employ different strokes for different blokes (read States), it is not my intention today to challenge their dubious claims to even handedness. That could come later.

My immediate purpose is to recall memories of the Berlin Wall which I saw almost daily during five months spent in West Berlin at the height of the Cold War nearly 50 years ago.

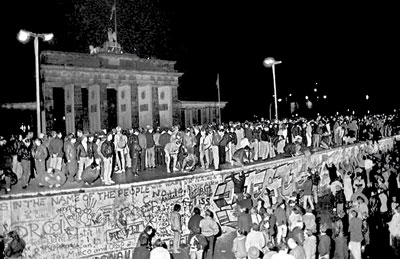

East and West German citizens celebrate as they climb the Berlin wall at the Brandenburg Gate after the opening of the East German border was announced in Berlin, on November 9, 1989. Reuters

In mid-1966 I was one of 12 Asian journalists selected to attend an Advanced Diploma Course conducted by the Berlin Institute for Mass Communication in Developing Countries, as it was then called with noticeable condescension.

There was one other participant from Ceylon as we were known. He was Rex de Silva, who had come into journalism about two years after I did and was to become my good friend. He later became the editor of the Sun and the Weekend Sun newspapers published by the Gunasena-owned Independent Newspapers Ltd and still later editor of the Borneo Bulletin.

Our Institute was in Kochstrasse, West Berlin, and almost opposite Checkpoint Charlie, the well-known border crossing in the American Sector. It served as a point of entry for bus loads of curious western and other tourists who wanted to see the capital of the Communist German Democratic Republic (GDR) or DDR in German, and compare it with western affluence.

The western allies encouraged visitors to go east and see the sparse shops with limited consumer goods and empty shelves, the poorly clad Germans compared with their West Berlin cousins and the dilapidated and dull buildings that epitomised life under communism.

We lived in good individual apartments in a town called Wedding. Each working day we took the “U Bahn”, the West Berlin underground train, to Kochstrasse station which was smack opposite Checkpoint Charlie and walked the 150 metres to the Institute stopping nearby for a quick breakfast of brotchen and bratwurst.

We had access to the dining facilities at the Axel Springer Verlag, Germany’s largest publishing house owned by the Springer family which published such well-known German newspapers as Die Welt and the mass circulating Bild Zeitung which sold some 4 million copies daily.

The Springer group was situated just by the wall and each day we would gaze at the war ravaged scene of crumbling buildings and empty spaces on the other side of the wall.

Before long I discovered that some of the lectures we were subjected to were more propaganda than journalism and meant to educate us semi- literate pen-pushers from the Third World on the evils of communism and the supreme bliss provided by western free enterprise capitalism.

“There were journalists from the Springer newspapers such as Stefan Gansicke’, deputy editor of the Berliner Morgen Post, a thorough professional and John Izbicki of London’s Daily Telegraph who provided valuable experiences to broaden our horizons.

“But among those who were supposed to bring enlightenment to us benighted journalists from the back of beyond were chaps from a station called Radio RIAS which I was later told was a station financed wholly or partly by Washington like Radio Liberty also operating out of West Germany, which some German journalists told me was a CIA operation.

Of course I had no proof of this but the substance and tenor of some of those lectures left little doubt that it was oft times propaganda sans subtlety.

My interventions in the lecture room supported now and then by Rex de Silva, challenging both the assumptions of some of the invited speakers and our colleagues from South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand whose unashamed parroting of pro-American views (it was the time of the Vietnam war) which were becoming increasingly annoying, did not endear me to the Institute’s director or some senior staff.

Five years before our arrival the Berlin Wall had sprung to life, physically and more tangibly dividing an already divided Berlin. It was one of the first sights shown to us shortly after our arrival.

Like in one of those old morality plays, the wall came to symbolise the ideological chasm between East and West. The wall and what was hidden behind it represented evil and West Berlin under the three allied powers, all that was good.

But what the propagandists there never mentioned is that the tale they wanted us to unquestioningly accept as the political truth was not as simple as they made out.

West Berlin was developed as the showpiece to prove the ultimate success of the western way of life over the drab and restrictive existence of the Germans on the eastern side of the wall.

The showpiece of this showpiece was Kurfurstendamm or Ku’dam for short, a couple of kilometres-long avenue with its glitzy restaurants, sidewalk cafes, night clubs, chic upmarket shops and the huge department store KaDeWe.

This was capitalist West Berlin’s answer to the Champs Elysees in Paris, perhaps the best known avenue in the world. The Ku’damm drew to its bosom not only the world’s glitterati but the cash-strapped and deprived East Germans from the other side of the wall who came to gaze at the relative splendour.

Free movement was then possible in the divided city, many East Germans coming to work in West Berlin. They were paid in West German Deutsche Mark which was four times the value of the East German Mark. This huge difference naturally attracted the educated and skilled workers from East Germany to West Berlin. It was not simply the desire for freedom and liberty, as our interlocutors would make us believe.

Perhaps the more compelling reason was that with the restricted opportunities in the East and the poor wages and facilities for the progress of their families those with qualifications and skills wanted by the West decided to migrate to the more affluent part.

Over the years the magnetic attraction of the West denuded the struggling East Germany of its educated and skilled men and women. The East German State system educated and trained its citizens. The West then enticed them over without spending a single Mark on the much-valued human resources. It was a win-win situation.

This was the flip side of the story. It happens even today and it is called the brain drain. History does repeat itself.