No longer a ‘sewage hell’ but woes remain

They were a community battered by the 2004 tsunami. After languishing in temporary shelters for some time, this group of tsunami survivors from coastal villages down south were resettled in the Turkish Village in Midigama, Weligama in 2006.

Signs of erosion

It was back in December 2009, that the Sunday Times highlighted how this tsunami village had turned into a ‘Sewage hell’ due to a malfunctioning waste treatment plant.

With the tenth anniversary of the tsunami approaching, we revisited the village early this month and were met by a scene of normalcy – housewives, attending to their chores, a grocery shop run by an occupant doing brisk business and children returning home after school.

Yes, they are getting on with their lives, but, some crucial problems persist – the issue of land rights being their biggest concern.

Curiously of the 450 houses built here, some remain unoccupied. Villagers say many of the original inhabitants sold their houses and moved out.

Most of the occupants, both the initial beneficiaries as well as those who had bought the houses from the original occupants, expressed their frustration about not receiving the

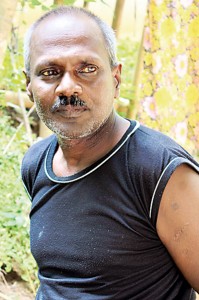

L.H. Ratnapala: A fisherman’s tale

deeds for their property, questioning as to how they could even carry out home renovations when they cannot prove ownership.

The houses, some say, are poorly constructed and the lack of drainage facilities leads to soil erosion during heavy rains. “Our houses get flooded. I don’t think we will be able to live here for more than five to six years,” said P.G. Sandamali, pointing at cracks in the walls and crumbling pieces of plaster. Now expecting her second child, she moved to the village from Denuwela in Weligama.

Sandamali’s memory of the tsunami horror has not dimmed. “On hearing the huge commotion and people screaming and running about, I dragged my husband and daughter from the house and ran to a nearby temple,” she says. All their belongings were gone in a matter of minutes.

“Life here is not that easy. Travelling is a big problem here, especially when it rains. It’s a long walk from one end of the scheme to the other. There are days that I have to go to the clinic in Wekada at 6.30 in the morning to get an early number. If I have money I take a trishaw to the junction– but it costs about Rs. 100,” she says adding that a bus service, at least for the schoolchildren would be a great benefit.

Access to medical facilities is a problem. As Nadeeka Subashini, a mother of two notes, there is an urgent need for a medical clinic. “The closest is in Wekada which is about one and half km away but with transport difficulties at night, we panic in an emergency,” she adds.

Sandamali points to crumbling pieces of plaster. Pix by Anuradha Bandara

This being a predominantly fishing community, the occupants also raised questions of the practicality of resettling them in an area far away from the sea. “We have to go to Weligama, Galle or Mirissa for our fishing. When we return at night, there is no transport and it’s the same in the early morning. So we are compelled to restrict our fishing activities to the daytime only and what we earn is barely enough for three square meals a day,” says L.H.Ratnapala, a fisherman.

The initial problem of sewerage has been solved with individual septic pits being given to each household by the authorities about two years back, instead of the earlier system where private toilet lines were directed to big gullies which fed a waste treatment plant. However, in some places the uncovered gullies carrying kitchen waste water emanate a foul smell still, says Mihiri Boralessa who lives close to such an open gully.

Others spoke of the harassment and intimidation they faced from those in the surrounding villages.

Gamage Chandralatha, 40, who moved to the village with her daughter and grand-daughter three years ago from Pathagama, Midigama runs a small grocery shop from her home.

“One night, three windows of my house were shattered by a drunken gang. I called 119 and reported the incident but no one came. They targeted my family because we are all women and new to the village,” she says adding that, once, a lorry bringing groceries was not allowed to enter the scheme for no reason.

Other villagers spoke of another incident of targeted violence. This is an indication that there is a lot more to be done in terms of reintegrating this community with the villagers in the neighbouring areas.

Even though there is a police post, a routine check is not done at night, occupants lamented. “Men of the village clash with men from the neighbouring Wekada village over petty issues,” said some villagers.

Even though there is a police post, a routine check is not done at night, occupants lamented. “Men of the village clash with men from the neighbouring Wekada village over petty issues,” said some villagers.

A Buddhist monk in the village, however said integration was happening.

“The situation was much worse before but now there are those from nearby villages who have never gone fishing before, who join those in the Turkish Village to go to sea,” he said.

Weligama OIC Chandimal Wijeysinghe said that villagers have not made any complaints on incidents of intimation and harassment and said action could have been taken against the culprits if they had complained. The Police Post, the OIC said, is not only for the Turkish Village alone, but for any emergency situation within the area.

| Land deeds and underhand sales Responding to why land deeds were still pending, Weligama Divisional Secretary, M. Liyanarachchi said the delay was caused by beneficiaries selling off their houses. Of the 450 houses in the Turkish Village, currently only 200 are occupied by the original beneficiaries, while the rest have been sold. “The land was sold through underhand means. We detected 96 such land sales,” Mr. Liyanaarachchi said. Officials at the Land Commissioner General’s Department, explained that once the Divisional Secretariat makes a recommendation to the Land Commissioner General’s Department with the necessary documents, including the Government Surveyor plan, the process of issuing deeds takes place. Thirty-four families in the Turkish Village have received their deeds and they are now ready to give the deeds for another 64 blocks. “However, deeds will be made as per the names of the original beneficiaries list in the Divisional Secretariat and not for those who have bought the houses from them,” says the DS. Another 63 houses are on temple land for which they are still in the process of surveying and paying compensation, she said. Sri Lanka’s Ambassador to Turkey, Bharathi Wijeratne said the absence of the initial beneficiaries has become a huge impediment in the issuing of deeds. “It’s not the fault of the Government, for they are all out to finish this process. Although it is temple land gifted for this cause after the tsunami, proper procedure has to be followed. The Government has to be careful as to who they hand over the deeds to,” she said. |