A royal invitation to supper on board the HMS Cornwallis

King Sri Vikrama Rajasimha, the last king of Kandy fell into the hands of Eknaligoda’s mob while taking refuge in the house of Bomure Udapitiye Arachchi at Gallehewatta, close to Meda Mahanuwara on February 18, 1815. This marked the extinction of the monarchy and the sovereignty of this island-nation so proudly maintained for nearly 2,357 years.

When the news reached Governor Brownrigg in Colombo, he was at dinner. Dr. Henry Marshall was one of the diners. He says that the Governor was so overwhelmed by the news, tears rolled down his cheeks.

King Sri Vikrama Rajasimha

A bulletin of intelligence published by the Governor’s command on February 19 announced that “…Devout thanks are due to the Supreme Disposer of events, who has enabled His Majesty’s (King George III’s) forces in the colony in the short space of forty days, without the loss of a single individual, to overturn a tyrannical Government, which for several generations has oppressed the people of the interior provinces in the island of Ceylon”.

The harsh words used such as “tyrannical government” and “oppressed people” mentioned in the announcement were really based on the information fed to the British by the disgruntled Kandyan aristocracy. In fact, the ordinary people of the island were happy and contented that they had a king – a king who was receptive to their grievances. On several occasions, he punished the all powerful dissaves for atrocities caused in the villages. There are no records of public discontent or any form of demonstrations by the peasantry against the king.

Dr. Marshall, F.R.S.E, who was acquainted with the deposed king, was impartial in judging the king. The king was certainly ruthless in punishing traitors who included family and sometimes the retainers of the offenders. However, following captivity, he displayed some remorse when he spoke about certain punishments pronounced at times when he was emotionally charged. The deposed king confided in Major Hook who was accompanying him that the English Governors had the advantage over the Kandyan monarchs in having counsellors about them who never allowed them to do anything in a passion. The remorse of the deposed king is evident by his words – “but, unfortunately for us, the offender is dead before our resentment has subsided”.

On arrival at the site of the capture D’oyly saw the mayhem caused by mobs directed by Ehelepola, Eknaligoda and Thamby Mudali. The queens were half naked with their jackets pulled off. The chief queen Venkata Ranga Ammal had her ear lobes torn when the gold ear ornaments she wore were snatched by the mob. The king was tied like a ‘hog’ with creepers. The English officers summoned by Dias (Don William Adrian Bandaranayaka) chased the mob and paid their respects to the royal captives. The king was offered Madeira while the queens were thankful for the diluted claret. The mob with their leaders was probably after vengeance for the cruelty the king imposed on Ehelepola Kumarihamy, her children and her sister. D’oyly had two pressing problems. One was to keep out the mob crying for revenge and the other was to lead the captives towards Kandy without creating the possibility of a general uprising by the ordinary Kandyans who were still loyal to their king.

The king, his four queens and the king’s mother dressed in clothes hastily collected were conducted on palanquins. Two chief British officers, one of whom was Major Hook, mounted their charges and with drawn swords took their positions on either side of the king’s palanquin. The English soldiers, horse and foot took up positions in front and at the rear of the group. Sri Vikrama, the last king of the Isle of Lanka embarked on his last journey through the kingdom which was once his. D’oyly planned to avoid the city of Kandy and took a devious route that went through Negombo. The royal party reached Colombo on March 6, 1815.

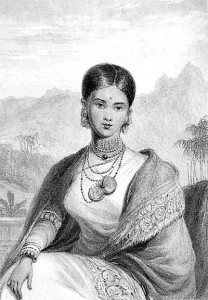

Ranga Ammal: Queen Consort drawn by William Daniell in the 1800s

The king and the royal family were introduced to Colonel Kerr, the Commandant of the Colombo garrison. The king and his family were provided with a spacious house fitted handsomely. Nihal Karunaratne mentions the document, ‘Narrative of events which have recently occurred in the Island of Ceylon written by a gentleman on the spot’ where the writer says that the largest apartment of the house had an ottoman covered in mustard coloured cloth on which the king sat cross-legged in an ungainly manner and had quipped, “…as I am no longer permitted to be a king, I am thankful for the kindness and attention which has been shown to me”.

The tiny, round, bullet head shaped structure with peephole windows in front of the Ceylinco building in Colombo Fort, labelled as the cell where Sri Vikrama was imprisoned may have been a small part of the spacious house of the King. Numerous letters written by the king asking for special provisions indicate that he was quite free and was not confined to a cell. He once asked the Governor for – one hat made of pure gold, one hat of superfine cloth mounted with gold and feather along the edge, two jackets, one of superfine white cloth, one of superfine embroidered, one flat neck ornament called mante, and a small dagger mounted of gold and several lockets mounted with precious stones, all of which he said he left in the Mahanuwara palace. He insisted that the above items were necessary when meeting gentlemen who visited him. His request for silver cutlery and crockery was equally impressive. The British maintained the king and his family, providing them with whatever they were used to as a reigning monarch and queens. But the king kept on petitioning for extra rations, items (in massive quantities) for his weekly bath and gold ornaments for his queens.

The way the British maintained the deposed king and his immediate family and the protocol followed on the day they were exiled to Southern India show how they feared the legitimate king of the land and how they stuck to royal etiquette wherever possible. The king and his family lived in the Colombo house from March 6, 1815 to January 24, 1816. The colonial government realised the problems that would crop up if the king was held in the island and was eager to locate him in Madras as early as possible. But the negotiations with the colonial counterparts in Madras were long drawn and finally, still without a definite final destination decided, the king and his retinue were eventully deported on Wednesday, January 24, 1816.

P.E.E. Fernando refers to E.I. Siebel’s description of the embarkation of Prisoners. The HMS Cornwallis captained by O’Brian was ready in the harbour. “The departure of the king from our shores took place on Wednesday afternoon about quarter after four on the 24th day of January, 1816. He was conveyed in great state from his residence near the south gate to the Custom-house in a phaeton of the Governor. . .. The phaeton was drawn by two thorough-bred Arabs belonging to His Excellency. The ex-queens, four in number, were accommodated with palanquins, in which they were carried to the wharf. The king on reaching the Custom-house alighted from the phaeton, and accompanied by Colonel Kerr, Deputy Commissary-General, and Mr. J. Sutherland, Deputy Secretary to Government (who were holding him by either hand) walked up to the palanquins and desired his queens to descend …. which they did very reluctantly. Their natural timidity or modesty induced them to stick close to their palanquins, and to decline to leave them, until forced to do so by their liege lord and master.

“Four boats were in readiness to convey the royal party to HMS ship Cornwallis, then in the offing; and the boat or barge intended for the king and his queens was very richly decorated, and had an awning of green satin ornamented with gold spangles all glistering in the sunshine like so many stars. The quarter floor was covered with a valuable white carpet, and the boat itself was manned with a very neat-looking and handsomely dressed set of rowers. ….. When his royal consorts had been safely placed in the barge, the king, divesting himself of his sandals, stepped into it; and standing erect was observed to look up to heaven, engaged in meditation. The king then sat down smiling, and, upon a given signal, the boat pulled off from shore followed by other boats which contained the king’s baggage and attendants.”

Captain O’Brien welcomed the monarch on board ‘with every mark of proper decorum’. The king followed to his cabin through the ranks of the Marines drawn up under arms. It is recorded that the king was dressed in a red silk cloth wrought with gold thread, baggy purple silk trousers secured to his ankles with ribbon, an embroidered jacket with a fine white upper dress with innumerable pleats, and a green silk mantle edged with gold lace worn over the jacket. A magnificent turban crowned his head and completed his attire.

The passage was rough at the beginning with stormy seas. The king’s behaviour too was rough at the onset but he settled down to a more sedate life on board. Major Hook and William Granville accompanied the royal family. Granville wrote the most comprehensive account of the king in a long winded essay – ‘Journal of reminiscence relative to the late king of Kandy when on his voyage from Colombo to Madras in 1816. A prisoner of war on board His Majesty’s Ship Cornwallis, by William Granville, His Majesty’s Civil Service’. This account was printed by the Wesleyan Press in 1832.

Granville’s account records an incident that showed the tender and jovial sides of the deposed king. The journey was long and on February 16, 1816, 24 days into the voyage, the king invited Major Hook, William Granville, Captain O’Brien, three other ship’s officers and Mrs. Sewell for supper in the royal quarters. It is said that the correct etiquette and decorum compelled the English to accept the invitation. Going on to the 24th day at sea it is evident that the ship’s larder was well stocked with the king’s favourite and familiar stuff. Sri Vikrama took hold of the planning and oversaw the preparation of a vast number of dishes unfamiliar to the English.

Granville says, “…Our assent was given of course with thanks for the favour intended to us. His Majesty did not come upstairs all the morning. But remained below superintending most anxiously the cooking of the various dishes. It was not without some apprehension that we contemplated the approaching feast. When we considered the strange materials of which and by whose orders it was composed. The King himself directed where every dish should be deposited, and seemed very particular about the proper position of each. Scarcely was one dish tasted by us, before the King, like Sancho’s physician, ordered it away and another to be brought. His Majesty felt that we should partake of what he called his favourite dishes, his energetic manner of recommending them, together with the fear of anything going wrong, or contrary to his previous orders, threw him into a violent heat and agitation, which served as salutary exercise to his unwieldy frame. I must own that I was happy when the things were removed. The greasy slops and other nausea spread before us, almost overcame me and produced diverse sensations of a tendency I need not expatiate upon. The variety of dishes produced on this occasion was surprising to us. Soon after dinner, we retired to the stern gallery when the King asked us if we had been pleased with our dinner. He laughed loud and heartily and seemed to think he had accomplished a great undertaking and one of uncommon merit.”

We do not know the details of the food that was served by the king at the supper on board. Konnusamy was 18 years when he was crowned as Sri Vikrama. Unlike his predecessors Kirthi Sri and Rajhadi Raja, he did not grow up in the palace. Nevertheless he would have been aware of the cuisine usually followed by the royal household. There were recipe books written on ola leaves for the royal kitchens of the Nayakkars. The recent publication of ‘Recipes from the Cookery Book of the last Kandyan Dynasty’ by Ananda Pilimatalawe shows a wide variety of food, including health foods and ‘taboo’ foods used by the Nayakkar monarchs of Kandy. Meat was part of the cuisine but almost always was game such as venison. It is doubtful whether the Cornwallis carried venison, at least in the dried form. Fish when presented was mostly fresh-water ones and other than dried fish it is almost certain that the ship could not have had fresh-water fish. The ‘greasy slops’ mentioned by Granville were most probably tempered dishes made with plant oils and clarified butter.

The deposed king was partial to English liquor particularly Madeira. It is not recorded whether any form of alcohol was served at his royal supper hosted by this colourful character who was a mighty king just a little over a short span of one year. The events of 1803, only 12 years earlier, where the English got almost annihilated at Watapuluwa, on the outskirts of the Kandy city, would still have been fresh in the minds of the diners, particularly of Major Hook. It is also not mentioned whether the host and the guests who retired to the stern gallery after supper had brandy, Madeira or fruit juice. Granville does not mention whether they – the English guests, took any presents when they attended the royal supper.