On the streets of Istanbul where a pair of lovers did love

The taxi driver in Istanbul is somewhat mystified. Yes, he knows of the street in Cukercuma but has no idea of a museum located there, let alone a museum set up by Turkey’s most famous literary figure. The street itself is narrow and poorly lit and we drive downhill peering anxiously through the glooming light. Then, there it is on the left. Not one of those grand mansions that dot Istanbul’s more swanky neighbourhoods but a tall angular building, only distinguished from the others on the street by its colour- a deep dark red, turned into rich burgundy by the deepening shadows.

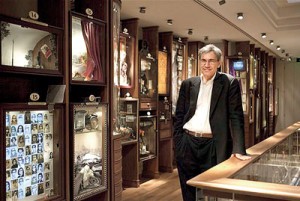

Orhan Pamuk in his Museum of Innocence. (Pix courtesy Museum of Innocence)

This is Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, a museum dedicated to his best-selling book of the same title which tells the haunting love story of Kemal Basmeini whose doomed passion for his poor relative, the delicately beautiful Fusun engulfs his life. Released in 2008, The Museum of Innocence was a bestseller but what is little known is that Pamuk all through the writing of the novel collected the artefacts displayed in the museum and in many instances let them take on a life of their own in the writing of the book. The museum was opened in April 2012 with Pamuk using his Nobel Prize money to set it up.

Our guide on this visit to Istanbul had asked us if we had our copies of the book and we replied, no, we had not brought them along. At the entrance, though his question took on new meaning. For the 25 lira entrance fee is waived for all who present their copies of the book for on the last page is the entry ticket to the museum (go – check your copy), proof if anything that the book and museum grew simultaneously in their creator’s mind.

There is a strange feeling of anticipation as we enter, almost like entering someone’s home for the first time, and indeed if we were to go along with the novelist, this is Fusun’s home where she lived, furnished with all the trivia and paraphernalia of everyday life. In 83 cases, the number corresponding to the number of chapters in the book, over the three floors of the house turned museum, we meet Fusun the woman who was Kemal’s magnificent obsession.

Perhaps the first exhibit on the ground floor is the most startling. It occupies a whole wall to the right of the entrance. Its contents are the most mundane, yet meaningful to anyone who knew Fusun –a collection of cigarette butts, 4213 in all, some carrying the marks of her lipstick, some burnt down, all mounted with a tiny inscription relating to when she smoked them. In the book, this is how Kemal describes the intimacy of the moment, how he secretly saved them. “During my eight years of going to the Keskins’ for supper, I was able to squirrel away 4,213 of Füsun’s cigarette butts. Each one of these had touched her rosy lips and entered her mouth, some even touching her tongue and becoming moist, as I would discover when I put my finger on the filter soon after she had stubbed the cigarette out.

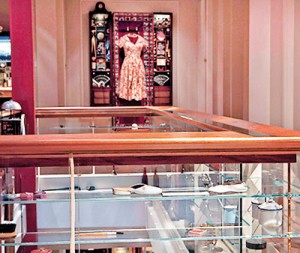

The second floor where Fusun’s dress is displayed

“The stubs, reddened by her lovely lipstick, bore the unique impress of her lips at some moment whose memory was laden with anguish or bliss, making these stubs artifacts of a singular intimacy.”

That installation so perfectly sets the scene for the Museum of Innocence and as we peer into each locked glass case containing an amazingly personal collection- toys, jewellery, clocks, glasses, keys, old photographs and other objects of a family, there is a feeling of turning the pages of Fusun’s life.

Narrow stairs lead from one floor to the other. Dominating the second floor is the case where the exhibit is a dress of floral print- a summer dress, Fusun’s dress, the heavy bead necklace suspended above as if indeed it lay on her milky white throat.

Up in the attic is Kemal’s bedroom where in the book he relates the story of his lost love to a young writer named Orhan Pamuk; a narrow bed, a suitcase, framed photographs on the shelf vividly recreate the scene. “Between 2000-2007 Kemal Basmeini lived in this room, where Orhan Pamuk sat and listened to his story. Kemal Basmeini passed away on 12 April 2007” reads the inscription. For the visitor, reality blurs, the thin line between seems to disappear. Perhaps this is what Pamuk intended, that readers who had lost themselves in the story would enter into Kemal and Fusun’s world, believing that yes, once upon a time, not so long ago, in the streets of Istanbul, this pair of lovers did wander, dine and love.

Time is alas, not on our side to mull over each exhibit. Hence we miss the audio installations, the recordings that bring alive Istanbul in the decades of Kemal- from 1950 to 2000. Down in the basement Museum shop, we hurriedly skim through the shelves but disappointingly find few editions of Pamuk’s work in English. There is a relatively pricey but beautiful catalogue in colour, posters of the Museum and other collectibles though. The friendly Museum host says that on average since its opening, they have had a steady flow of visitors, between 80-100 a day though of course, winter months see a drop. Since our visit, the Museum also has audio guides, with Orhan Pamuk himself explaining the exhibits in Turkish.

If not yet widely known in Istanbul, international recognition for the museum has nevertheless been forthcoming. It won the 2014 European Museum of the Year Award and a replica of box (exhibit) number 14, ‘Istanbul’s streets, bridges, hills, and squares’, was exhibited at the Design Museum in London.

Can you enjoy the Museum of Innocence if you have not read the book? Yes, if viewed as a snapshot of the Istanbul of that era, when Western modernity clashed with traditional mores that governed society, a theme that runs strongly through the book. One exhibit tellingly is a newspaper clipping of women with their eyes blocked out. This was the punishment in those days for the young women caught in pre-marital sex….a public shaming in print. Pamuk’s passion for his hometown, we realize, is as far reaching as his collection for Kemal and Fusun.

It’s past the 9 o’clock closing time and as we leave and walk down the street in search of a taxi, we pass a couple seated on the street at that late hour, surrounded by a motley collection of goods for sale. The thought occurs that it must have been from jumble sales such as this that Orhan Pamuk built up the Museum down the street… a collection which is in its own way a magnificent obsession.