Collage of fragmented memories

“When I am narrating this story to you, I am thinking of how the Indian army [the IPKF] burned our house,” says Thamotharampillai Shanaathanan, his voice strong as it comes over a phonecall from Jaffna. “That itself was not the most painful thing – it was what was left behind. A cup, but the saucer is missing, the book is burned but the cover is there.” To Shanaathanan these fragments are a nagging reminder of incompleteness, of what was lost. Without it, forgetting might at least be an option. Now a broken chair is part accusation, part verdict: “you have failed, you realise it cannot be fixed.”

T. Shanaathanan

It is this utter fragmentation that the Jaffna artist sets out to capture in DIS/PLACEMENT, his latest exhibition at the Saskia Fernando Gallery. Divided unequally between two series – one titled ‘Landscapes’ running from I through IV, and the other ‘Place’ from I through XX – the collection both builds on themes that have obsessed the painter and simultaneously marks a decided deviation from what was recognisably his style. Shanaathanan freely acknowledges the former, and seems intrigued and amused by responses to the latter.

He knows for the serious collector, this dilution of his aesthetic could be an issue, but Shanaathanan seems less interested in selling paintings and more interested in excavating truths. In the four ‘Landscape’ paintings he returns to his fascination with maps, which in his hands have long had a multi-dimensional quality.

Physically they are fascinating collages: the terrain crumples into hills and valleys of papier-mâché and sutures make for crude surgery that do little to hide the wounds in the earth beneath. Raw geography is overlaid with myth and memory: here the four rivers meet; the earth spirits pray, the walls and courtyards of demolished homes and temples still stand, and the bodies of the fallen throw their shadowy outlines on the land.These maps on their mottled and stained canvases seem to have the authority of age, and yet migration and war have made their borders unreliable; unrecognizable to those who once called it home. “This experience of displacement, of a feeling of loss, that actually becomes a common identity,” says Shanaathanan.

The artist created the ‘Place’ series in a process he describes as “different hands operating,” and in succeeding reminds us that he was also trained as an art historian. There is an impressive diversity of technique here – inspired by everything from the Renaissance to temple paintings and the traditions of realism and miniature canvases.

In one fragment, a richly dressed woman averts her doe-like eyes, in another the twin beams of a car’s headlights illuminate a bad road. There’s a shot of a helicopter hovering, ominous and black; the torso of a naked woman, the scales of a fish, a tractor in a field, an aerial view of a house. There are tiny, white flowers on the vine, a statue on a plinth, a mermaid, a hospital bed abandoned to the elements, a set of dentures that even minus its owner still manages to grit its teeth.

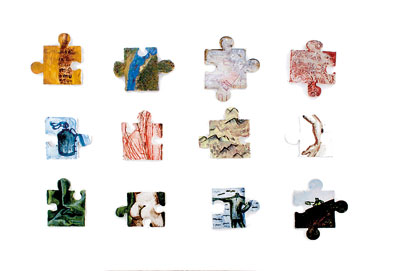

Over 200 jigsaw pieces were created for these 20 ‘Place’ paintings – the layout of which were inspired in part by the insect boxes the artist was fascinated by in the Natural History Museum. The splintered presence of each piece serves only more strongly to underline what is absent and the seeming impossibility of completeness.

“Some of my viewers are not happy with this exhibition,” Shanaathanan admits. He has been told that his signature style is not visible here. While this is true to some degree, it is equally obvious that DIS/PLACEMENT is an iteration of the artist’s long engagement not just with themes of identity and belonging but with jigsaws.

They first appeared in his 2006 exhibition ‘Locating the Self’ where the headless torso of a man held five or six pieces. Shanaathanan used the work to explore how location and identity were so entangled, that to disconnect one was to mount a profound challenge to the other. Then again he returned to jigsaws with his extraordinary book ‘The Incomplete Thombu’ the very last page of which featured the story of a woman made a stranger in her own street because none of her community remained. For Shanaathanan, the jigsaw he created in response to her story reflected the plight of the Muslims from the North and the East who had seen violence and eviction strew their people across the island.

He says now that that story became the starting point for ‘Mismatches,’ his next exhibition in 2012. There he created nine individual jigsaws, each representing the nine planets or navagraha of Hindu mythology. They represented different memories, incidents and experiences, says Shanaathanan.

With ‘Mismatches’ he knew what appealed to his audience: “It worked very well in the exhibition space. People, they will buy that – they will not buy the tensions, they will buy a beautiful jigsaw piece.” The exhibition seems to have made two things clear to Shanaathanan: he was not done with jigsaws and he was keen that his work represent the political violence and social complexity of his context. They should not be easy to treat as merely decorative.

Though in this case intensely personal, this exhibition also harks back to ‘History of Histories’ (2004), in which the artist curated an installation of everyday objects ‘representing the memory of home,’ collected from 500 people from across the Jaffna peninsula. The exhibit was installed in the newly restored Jaffna Library but was unaccompanied by any form of registry, labels or explanations. Donors who could not tell their pieces of barbed wire, broken dolls and bullets apart from those others had contributed were forced to confront the enormity of their shared suffering and often broke down, remembers Shanaathanan.

He would later recreate the project for the Vancouver Museum of Anthropology, working with the Sri Lankan diaspora in Canada. (Initial plans for a tour of the original exhibit were shelved when faced with the troublesome process of gaining exit permits for the objects, the possession of some of which, such as passports and bullets, was actually illegal.)

Shanaathanan’s portfolio of work is best appreciated in his personal context. The artist is not removed from the violence and sorrow he documents with such effective subversion. He lives and works in Jaffna, where he teaches art at the University and when he is not there, he must still contend with the knowledge that his parents are. (In fact, his family were among the hundreds of thousands forced out of Jaffna by the LTTE in the 1995 Exodus.)

Though he admits he once toyed with the idea of leaving to try his fortunes abroad, like so many already have, Shanaathanan has long since consciously chosen to remain. It is because his art is so much of this place, and of this time that he would not recognize himself elsewhere. In remaining, he has given us a unique voice that records and responds to the suffering of a people. In successfully subverting censorship in his art, he has made room for dissent and sorrow, where seemingly none existed.