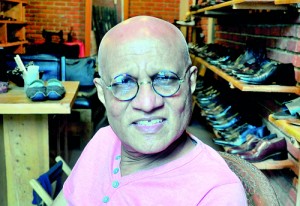

Inside his shoes

Sunil Samaratunga sits in his store, surrounded by hundreds of shoes. Over the years, ‘Sunil’s’ has become synonymous with good leather, but for the shoe maker all his decades in the business have been somewhat lonely ones. Describing himself wryly as the “last of the Mohicans,” Sunil tells the Sunday Times that shoe making is a dying art, one he’d very much like to see revived in Sri Lanka.

Sunil Samaratunga: A long journey with his shoes

His entry into the trade was by the way of a friend of the family. He apprenticed at Lucian Mellawa’s City Foot Wear on Canal Road, joining at the tender age of 21. His father was an electrician and his mother a seamstress and Sunil’s family had struggled to raise the money for him to keep studying, but here under the watchful eye of shoemakers who had been at work for generations, Sunil says he was lucky enough to discover his passion.

“As an apprentice, I was meeting clients and speaking with them,” he says. He would, he says, “see everything through shoes.” It would be the first thing he noticed about anyone he met, and when inspired, shoe design was his medium of expression. But even as he was discovering his future vocation, Sunil knew he would be starting from scratch. Times were hard – “we were fighting for survival.”

As his confidence grew, Sunil considered branching out on his own. In 1971, he made a start, renting a garage on Galle Road for the princely sum of Rs. 105 for three months. His personable customer service won him a loyal fan base and he found he could afford to rent a few racks in a textile store a few blocks down. In return he would give them 15% of his income, but really Sunil got the better deal, for it’s here he met his wife Kusum, then a cashier at the store. In her he saw “an ideal partner for my kind of work, she was poor and I was poor but we got together and made our own empire.”

Last year they celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary and their partnership has resulted in a very successful business. Though old customers will remember Sunil’s outlet on Galle Road, it’s in the shop on 19th Lane that he’s come closest to attaining his dream of one day owning a gallery of his own. The place is packed full of shoes and bags but even as we speak, a customer comes in asking Sunil if he would custom design a shoe.

The process the two will go through is one Sunil is completely familiar with. He says his designs take into consideration not just what his customer wants but things like their profile and body type – for a customer with very small feet for instance, he might design an elongated shoe that balances out their body profile. The kind of leather also determines the look of the shoe. Sunil says he works with sheep, cow and goat  leather, but that it remains one of the hardest materials to source in the quality and quantity he requires.

leather, but that it remains one of the hardest materials to source in the quality and quantity he requires.

Skilled craftsmen are the rarer resource these days though. His team is made up of some 15 men who are divided into people who do the soles and others who create the top parts of the shoe. They work at the back of the store, says Sunil, whose focus remains on design. Going on his 45th year in the business, he’s often struck by a sense of déjà vu. “I haven’t seen anything new,” he says, pointing to the latest fashion so reminiscent of the pieces they were producing in the 60s. His own personal inspirations have been the gods of shoe design – people like Salvatore Ferragamo and Manolo Blahnik. (In the shop are posters paying tribute to Ferragamo’s designs for Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe.)

“Our kind of shoe making is a dying art,” says Sunil. It’s not hard to see why – with days required to finish a handmade shoe, and “hundreds of stages” in their making, affordability isn’t guaranteed. Sunil is turning the latter into his selling point though, and claims “I’m the most expensive in Sri Lanka,” listing his prices at over Rs.10,000 for men’s shoes and over Rs. 5,000 for women.

Deploring mass produced shoes he argues for a shoe industry based in Sri Lanka and says the National Crafts Council should recognise it as a valuable skill and train people in it. “There is so much more to it than meets the eye,” he says. Making his case is his own success in an otherwise neglected field. Despite the challenges of keeping his customers coming back for his expensive product, Sunil sees his work as a blessing, something that has allowed him to feed his family and educate his children. “Everything, I did through this,” he says.

S.D