Sri Lanka sparks revolution in South Asian history and archaeology

View(s):It is an amazing ‘message’ that has lain buried in the sands of time in the ancient city of Anuradhapura. First brought to light in the late 1980s by Dr. Siran Deraniyagala of the Archaeological Department that early settlers in Anuradhapura communicated through the use of the Brahmi script long before the Ashokan period in India (during which time this script was earlier believed to have come into use), parallel evidence has now emerged in South India.

Dr. Siran Deraniyagala. Pic by Nilan Maligaspe

This changes the history of South Asia and is considered “momentous” since the discovery of the Mahavamsa.

Transfer of information depends on writing and here the Sunday Times details how this information technology revolution was unearthed in the 1980s in Sri Lanka and confirmed in research publications last year in India.

Archaeological research excavations were conducted in the ancient administrative centre, the ‘Citadel’, of Anuradhapura by Dr. Siran Deraniyagala of the Archaeological Department in 1988. They probed the origins of the settlement at Anuradhapura, at depths of nearly 30 feet below present ground level. Contrary to hitherto held belief, these beginnings were scientifically (radiocarbon) dated to around 900 BC, with a settlement area of as much as 35-65 acres, representing a large village. The associated cultural material comprised the use of iron tools, paddy cultivation, high grade pottery and the rearing of horses and cattle (Deraniyagala 1990, 1992; Deraniyagala & Abeyratne 2000).

By 700 BC the settlement covered over 125 acres, and by 500 BC a city of around 180 acres. Subsequently, in the 3rd century BC during the reigns of King Devanampiya Tissa and Emperor Asoka of India, the Citadel had reached its peak of over 250 acres. The latter represented the largest city

Brahmi script

in the region south of the North Indian city of Ujjain (Allchin 1995: 208).

The development of cities on the Indian sub-continent, from about 1000 BC onwards, was focused primarily on the Ganges valley in the north, as represented by the city of Kausambi. This cultural florescence is referred to as India’s Second Urbanisation. It came as a revelation that Anuradhapura, far to the south of these North Indian urban centres, should have had a parallel development which, as per the present evidence, was not matched anywhere in peninsular (central and southern) India. The cause of this anomaly is a matter of intense debate among archaeologists internationally.

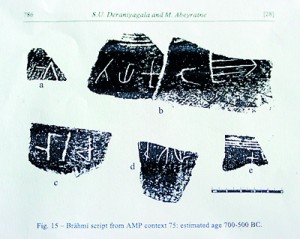

One of the crucial pieces of evidence to emerge from Deraniyagala’s project was the discovery of pieces of pottery, from seven different vessels, inscribed with Early Brahmi script. (Brahmi was the first script to have been used in South Asia.) The potsherds were found in two widely separated excavations from horizons scientifically (radiocarbon) dated to 600-500 BC (Deraniyagala 1990, 1992; Deraniyagala & Abeyratne 2000).

The orthodox thinking, as expressed by the eminent South Asian archaeologist, Dr F.R. Allchin (2006: 453) of Cambridge University has been:

…nowhere since the initial discovery and reading of the Asokan inscriptions by James Prinsep more than a century and half ago, have any inscriptions been discovered which can either be dated or proven to be earlier those of Asoka [who reigned between 274 and 232 BC].

The evidence from Anuradhapura was a startling contradiction of this view. Its publication (Deraniyagala 1990, 1992, 2000) spawned considerable scepticism, particularly among historians. A noteworthy exception was India’s foremost expert on ancient inscriptions, Professor Iravatham Mahadevan, retired epigraphist of the Indian Archaeological Survey, who on receipt of the 1992 publication wrote on 11 Sept. 1997:

Dear Dr. Deraniyagala

I thank you very much for the offprint of your paper sent along with your letter of 6th August. You seem to be indeed making a revolution. The only problem is that supporting evidence is not yet forthcoming from India. When this happens, your revolution will be complete [my italics].

Yours sincerely,

I. Mahadevan

Meanwhile, in view of the (unpublished) scepticism evinced by several historians (primarily) and archaeologists on the validity of the 6th century BC dating of the inscriptions from Anuradhapura, at Deraniyagala’s suggestion the Archaeological Department invited a team of specialists from the U.K. to test his conclusions. This team led by F.R. Allchin and his assistant Robin Coningham (now of Lumbini fame), did so by expanding one of Deraniyagala’s excavations (Salgahawatta) in 1989-1992 Coningham 1999, 2006). The results conclusively confirmed Deraniyagala’s findings: pottery inscribed in Brahmi script was found in layers radiocarbon dated from 450 BC onwards (Coningham & Allchin 1995: 176; Allchin 2006). This was slightly more recent than the dates secured by the Archaeological Department, but nonetheless antedates Emperor Asoka by several centuries – which led to Allchin’s comment cited above.

The next episode in this saga is the sequel to Mahadevan’s comment cited here. Professor K. Rajan and his team from Pondicherry University excavated two Early Iron Age sites in the Kongu region of Tamil Nadu: Kodumanal and Porunthal (Rajan et al. 2014). Two (uncalibrated) radiocarbon dates of 408 and 330 BC respectively were obtained by him from Kodumanal for two specimens of pottery inscribed in Brahmi script. (Note that the actual calendric ages would have been earlier.) The Porunthal excavations produced two pottery ring-stands with Brahmi inscriptions. One of these was radiocarbon dated to 490 BC, uncalibrated – which once again would signify an earlier calendric age. Rajan et al. (2014: 82) conclude thus:

These dates…from Porunthal, and…Kodumanal assigned to the Brahmi script clearly two hundred years earlier than Asokan…Brahmi prompt us to have a re-look [at] the origin of [the] Brahmi writing system in India.

The discoveries of Rajan et al. in India take us back to Mahadevan’s statement: “The only problem is that supporting evidence is not yet forthcoming from India. When this happens, your revolution will be complete.” India has now produced the requisite evidence corroborating the Sri Lankan finds of 1988, that Brahmi does indeed predate the reign of Asoka by several centuries. The ‘revolution’ as postulated by Mahadevan, is complete.

The acquisition of a writing system represents a quantum leap in the development of information technology in any culture. The new dating for the beginnings of writing in South Asia, stemming from the discoveries of Deraniyagala in Anuradhapura, has activated a paradigm shift in the archaeology of South Asia. It is noteworthy that the traditional view that the Early Historic period began in India with the reign of Emperor Asoka in the 3rd century BC has now been revised to have commenced in the 6th-5th centuries BC (Rajan et al. 2006: 62). The impact of the discovery of the inscribed pottery from Anuradhapura can only be matched in significance by that of the Mahavamsa when first studied in the early 19th century. Sri Lanka can be proud of it.

Dr. Siran Deraniyagala acknowledges the support he received for the Anuradhapura Citadel project from the then Commissioner of Archaeology, Dr Roland Silva. And, of course, he expresses his thanks to his superb team of excavators from the Archaeological Department, headed by Alfred de Mel, who effected the sampling of artefacts and their contexts with exemplary precision.

Postscript. The Citadel of Anuradhapura, a rectangle of 250 acres is located between the Thuparama and the Twin Ponds. It is, without any doubt, the most important archaeological site in Sri Lanka. Only 1/10,000th of its ancient cultural contents have been excavated so far. The rest lie undisturbed within nearly 30-foot depth of deposits. Meanwhile, despite this area being protected by the Antiquities Ordinance (gazette notification), it is subject to intense encroachment. Urgent measures are required to halt this rapid erosion of an irreplaceable resource (within the World Heritage site of Anuradhapura). The nation awaits.