Sunday Times 2

Is ‘SRILANKA’ the magic healing mantra?

View(s):On May 22, 1972, at least one person said the new two-part name SRI LANKA did not bode well for the nation. A decade later began a devastating war that bled the country for 27 years — and often threatened to tear it apart.

What’s in a name, asks Stephen Prins

Some are saying that Astrology has been caught out at last. Two weeks ago, the popular art or science (or both combined) of divining Earthly developments from planetary movement suffered an embarrassing setback after a local astrologer predicted inaccurately and tripped up a government. One miss on the part of one astrologer does not make Astrology suspect. That would be like saying Western Medicine is dubious because one dengue patient expired at the hands of one inept doctor.

Years ago, an amateur astrologer, the late Mr. Elmer de Haan, was a regular visitor at our home. He was better known as a superlative musician and music teacher, and a feared music critic. Astrology and palmistry were more than side interests; they were crucial weather charts for the times and climes Mr. de Haan lived in.

We have a vivid memory of one particular visit, 43 years ago. It was May 22, 1972, a historic turning point for the country. The day is burned into our memory as if lightning and thunder had detonated simultaneously under our roof. Mr. Elmer de Haan was the cause of the blinding flash and deafening clap.

That historic morning, at an auspicious hour, during a solemn ceremony held at the Navarangahala, the country was declared a Republic, a new Constitution was unveiled, and CEYLON was replaced by SRI LANKA. After 500 years, the last official traces of foreign rule were erased and a new beginning was heralded.

The new name, Sri Lanka, was something English speakers were going to take time getting used to. Some liked it, some rejected it outright.

Mr. Elmer de Haan was in high stormy form. “So what do you think?” he thundered as he strode up the back veranda. His normal speaking tone was a lion’s roar, and whatever he said was heated, controversial, a shock to the system.

“Changing a name for the sake of a name change is bad enough,” he said, as he took his usual seat facing Father, “but changing to a name that is two separate parts is worse. Mark my words, the new name won’t bring any good to the country.”

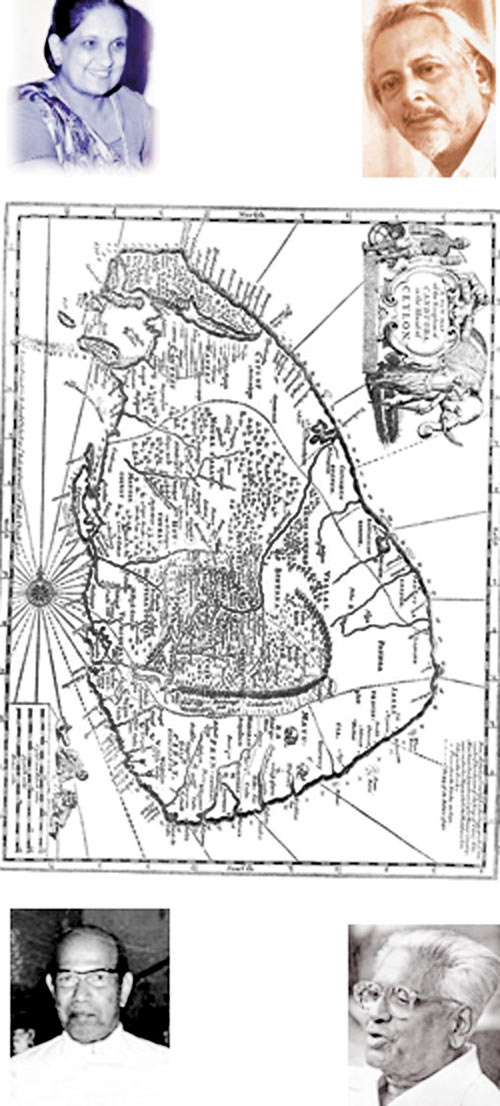

Island of many names - old map of "Ceylon"; clockwise from top left: former Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike presided at the first Republic Day ceremony on May 22, 1972; citizen Elmer de Haan, finely attuned to national developments and cosmic signs; Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, architect of the New Constitution, and William Gopallawa, First President of Sri Lanka.

To appreciate this story, the reader must understand a few things about Mr. de Haan, the outrageous, uncontainable agnostic-atheist who was one of the most extraordinary minds this country has produced. To put him in a word, Mr. de Haan was a phenomenon, but he defies adequate description. Those who knew him would attest to his overpowering persona and unholy, iconoclastic take on the world. He was up on any topic you cared to bring up. His conversation topics went from A to Z, but the areas in which he shone, or rather blazed, were M for Music and P for People/ Politics/ Politicians. In conversation he was mischievous, explosive, slanderously entertaining. His music reviews were steeped in ridicule and bellyful of libel. His laser-sharp character judgements and situation assessments were spot on. Mr. de Haan’s interest in astrology and the esoteric only added to his colourful, prismatic personality.

One of his claims was that the names of people and things, and their alphabetical components, have a powerful bearing on the name’s owner. The name a person receives at birth reverberates throughout the span of his life. Likewise with a nation; tamper with the sacred relationship that exists between a country and its long-established name is tantamount to jeopardising the country’s equilibrium, its future. Names are fate.

What happened that day

That day, 43 years ago, the colonial umbilical cord was finally severed. The Queen of England was no longer the Head of State. Dr. Colvin Reginald de Silva, Minister of Constitutional Affairs and Plantations Industry, was honoured as the architect of the new Constitution, William Gopallawa was signed in as the first President, and Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike vowed to continue to do her bit as Prime Minister.

It was clear that the day’s official proceedings had annoyed Mr. de Haan.

Elmer de Haan was a Burgher who was exceptionally proud of his Dutch heritage. A Governor of Batavia was a direct ancestor, he claimed, and the Governor’s brother was a Roman Catholic Cardinal in Holland. Like many of the local Burgher community, Elmer de Haan resented the gradual uprooting of the colonial inheritance. The country’s glory years were the previous five centuries of Western rule.

There was another cause for Mr. de Haan’s hyper-irritability that evening. The new Constitution had been written by an intellectual rival, a 1920′s classmate at Royal College, Colombo. An ancient schoolboy competitiveness glinted dangerously in Mr. de Haan’s eye. Like an ambitious student vying for the top mark in essay writing, Mr. de Haan was implying that he could have written a better Constitution – or written the Constitution better. The two aren’t the same – the former is about content, the latter about language, style and presentation, and Mr. de Haan, if you asked him, was top of the class in all these aspects.

The May 22 signing at the Navarangahala, the futuristic theatre-cum-conference hall later built on the site of our primary school hall, took place at 12.34 pm. Just as the ancient Romans consulted the haruspices, who slit open chickens and sheep to study their innards for signs to guide their leaders, the local Government would have consulted its astrological advisers on the new name. But had the advisers covered every point, every detail?

Over the past 2,500 years, this island has worn a sequence of gold-sequinned, gem-embedded names — Lakbima, Lakdiva, Thambapanni, Ilankai, Salike, Simoundu, Serendib, Tabrobane, Seyllao, Ceilao, Zeilan, Ceylao, Ceilon. The names are all metal-hard, one-piece units. The new name differed in being a pairing of two separate units. A single pearl-and-silver earring, and a single ruby-studded gold pendant. The name was binary: SRI, for radiant or holy, LANKA, for island.

To switch metaphor, the name parts were two distinct organic quantities, without even a slender connective tissue of a hyphen ( – ) to bind them together.

A musician with a hyper-critical ear, Mr. de Haan found CEYLON soft and euphonious, easy on the tongue, pleasant on the ear. The consonants C, L, N blended the vowels E and O with a liquid sweetness. SRI LANKA, on the other hand, was knotty; the first part coupled S and R in an Asian fusion of consonants that stuck on the native English speaker’s tongue; the consonants of the second part, LANKA, had a clanky percussiveness until you got used to it. SRI LANKA was hard and dissonant on Mr. de Haan’s Westernised ear, whereas CEYLON had a mellifluous Western-inflected cadence. It was as simple as that.

The social symphony

For all his outward raspiness, Elmer de Haan was a sensitive Romantic inside, his artistic temperament fine-tuned to the minutest fluctuations of harmony and effect, whether he was responding to a symphony or the soap opera of society. Far from being a reclusive music lover, dwelling in an ivory-ebony tower, loftily cut off from the rest of civilization, Mr. de Haan was very much in the mainstream. His conversation was 90 per cent current affairs and 10 per cent music, the fine arts, and philosophy (his own, of course).

Thanks to a network of well-placed friends, Elmer de Haan was a well-informed citizen, equally aware of what went on at street level and in the corridors of power. Purveyors of the latest political gossip relished his feedback which, like his music reviews, was hilarious and most unkind. He especially delighted in skewering pompous egos in Parliament. Claiming a man or a woman’s face told you everything you needed to know about that person, he would study the daily newspapers and pounce, saying, “Here’s a rogue, there’s a rake.”

Access to confidential information was never a problem. Mr. de Haan obtained birth dates and times of people who kindled his interest. The political ascent of Mrs. Sirimavo Ratwatte Dias Bandaranaike was of immense interest; the horoscope he cast, he said, explained every step in her progress, from housewife to the world’s first woman prime minister; her summary quelling of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna rebellion in ’71 was true to character, Mr. de Haan said. He may have been critical of the PM, but he respected her. She was where she was because the zodiac had decreed so.

The closest we ever came to Mrs. Bandaranaike in person was when we stood right in front of her a few months after she was elected Prime Minister in July 1960. We were 10 years old, she was 44. She was chief guest at our primary school prize-giving, and was handing out our graduation certificates. She was dressed in white, being still in mourning for her assassinated husband, the previous Prime Minister, Mr. S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. On the flower-decked stage, in a setting of white lilies and lotus blooms, she looked like a swan, tall and regal. As it happens, she was standing at the very spot where she would sign the Republic Act 12 years later.

As we clattered up the wooden steps, we looked up in the hope of catching the PM’s eye, but her gaze was elsewhere. She was looking out over the crowd in the hall. She was looking at the future, conscious that the world was looking at her. The 10-year-old clutching his graduation certificate thought the new Prime Minister quite beautiful.

Astrology vs. modern science

The scary part about Elmer de Haan was that his prognoses would unsettlingly come true. We once asked him whether astrology and palm reading could stand up to modern science. His answer was that his readings were confirmed time after time. To ignore a de Haan prediction was to take a risk

Here are three examples of Mr. de Haan’s uncanny astrological insights:

In the 1930s, he predicted an outstanding music career for a child born to intellectually and artistically gifted parents; the child grew up a music prodigy and later became a concert hall celebrity in Britain and Europe. He was born on the stroke of noon, with the sun directly overhead, during an astrologically favourable phase. Solar influence at its most intense meant that brilliance was to be expected in the child, and brilliant the boy turned out. He was a math wizz at St. Joseph’s College, Maradana, and he broke the school principal’s heart when his artistic mother decided his career would be music, not math.

This oft-heard story came from Mother, who knew the family well and worked on concert progammes with the musician whenever he was on holiday.

In another case, concerning two children of parents also known to Father and Mother, Elmer de Haan foresaw a bright, glamorous future for one and a difficult gloomy life for the other. Surely enough, over time, one went on to enjoy a successful career as an artist-professional, while the other had a struggle all the way, from childhood to adulthood. The less fortunate child was born at midnight, when the sky was at its darkest and deepest, and for that and other zodiacal reasons would have a “hard life.” Things turned out as Mr. de Haan had said they would. “Some are Born to Sweet Delight, Some are Born to Endless Night,” the poet William Blake intoned 200 years ago.

In another quite different situation, the perspicacity of Elmer de Haan the Astrologer was brought home to us with the impact of a cannonball fruit falling on our head.

A schoolmate of ours from a respected Galle clan requested the favour of a horoscope from Elmer de Haan, who knew the family. He wanted an assurance that life in Australia would suit him. Mr. de Haan collected the date and time of birth, and three days later we turned up at his Kensington Gardens home to hear what he had to say. Dressed in sleeved vest and striped pyjamas, Mr. de Haan leapt up from his veranda chair and bellowed, “You are having an affair with someone in your house! Don’t deny it.”

We looked at each other in astonishment. Mr. de Haan must have guessed from the look on our faces that he had struck home, so to speak.

It’s all in the stars

Indeed our friend was having an affair – and with someone in his household – but how on Earth or Moon could Elmer de Haan have known? The affair, conducted discreetly with an attractive village lady who was ayah to his brother’s baby daughter, was as clandestine as our friend could make it, and the only people in the whole world privy to the secret were four classmates. And now Mr. de Haan too was in on the secret. But how?

Dazed, we took our seats, and Elmer de Haan continued. “I don’t know or want to know who it is you are carrying on with, but your horoscope shows clearly that right now you are in the thick of a serious affair with someone who sleeps under the same roof.” Mr. de Haan looked at his notes and went on with the rest of his reading. We left late that night, in shock. How can anyone say that astrology is mumbo-jumbo, we asked, as we reeled along under a sky vibrant with the stars and planets.

In later years, we joked that secret romances between servants and master and family were commonplace in feudal Sri Lanka, where homes had armies of servants, from ayahs and cooks to houseboys, chauffeurs and gardeners. But that covert social reality did not devalue Mr. de Haan’s stunning disclosure.

When the subject of astral bodies and their mystical hold on Life on Earth entered a conversation, Elmer de Haan would say that scientific discovery did not undermine truths that Primitive, Stone or Bronze Age man saw written in the book of the heavens. These celestial scripts have been read and ratified over millennia by intelligent and wise men, some of them antecedents of Galileo, Newton, and Einstein. Five centuries of scientific breakthrough do not dislodge 5,000 years of accumulated wisdom. Man’s naked eye sees things the modern telescope is not equipped to reveal.

All those dazzling, idiosyncratic revelations and insights — on any topic under Sun or Moon — came to an end with Elmer de Haan’s death, by cancer, in 1979. He was 73. Deryk Prins died a year later, in 1980, aged 62. Mr. de Haan’s utterances would continue to resound in the memory long after.

In 1986, we found ourselves in another part of the world, working in arguably the world’s most challenging city. Making the mental switch from Hong Kong to Sri Lanka was an effort. When we did tune to home, we heard news that was invariably depressing. The War in the North and then the East was going from bad to worse to horrific. Such was the pattern of national tidings over our next two decades overseas.

Cracks in the 3-D Map of Ceylon

Back in the ’60s, in our primary school years, there was a clay model of the Island of Ceylon displayed on a table outside the Headmaster’s office. The class would get to see the raised-relief map on its way to a scolding or a caning. The central highlands were a dusty purple massif that sloped off to the encircling olive-drab low country and the fading shoreline and ocean. This three-dimensional representation of home would pop up in the mind’s eye with each bulletin of War news.

Then, during one especially horrendous episode in the armed conflict, something clicked. In those wrenching years, home realities impinged on our conscious and subconscious minds. In dreams, we saw the country cracking up.

For some years, the clay model was showing cracks on its surface. Hairline at first, the jagged lines joined up and appeared as a clear fault line, almost a fissure. The imminent break ran from the top, the North, down the middle, swung eastward and stopped at a point low on the southeast coastline.

Two and two instantly added up, then multiplied: Separatist Struggle. Fears of Division. Territorial Demands. Map Reconfigured. New Borders Drawn. Serious Political Fracture. Forces Tugging in Another Direction.

The late Elmer de Haan’s May 1972 warning came booming and echoing across the miles, the years.

From then on, a hyper-real image of the cracking-up clay model of the Island would float into view, alongside each fraught War update. “Didn’t I tell you?” the spirit of Elmer de Haan whispered deafeningly in our ear. The cracks that threatened to separate the map model into two parts showed one part as roughly one-third of the whole.

S-R-I-L-A-N-K-A is eight letters wide and deep. The three letters S-R-I are around one-third the extent of the eight-letter stretch of SRI LANKA, or SRILANKA.

By the way, a political call for a separate territorial entity in the island was first heard in 1973, a year after SRI LANKA was renamed.

If Citizen de Haan is to be credited with metaphysical insight in the country’s fortunes, then perhaps a review of the two-part name may be in order. The space between the two name parts may be viewed as an existential gap, an abyss ringing with a magnetically charged yearning for the two parts to snap together.

Has there been any official fusing of the two? One that has brought benefit?

SriLankan, the national airline, has done it, in its way. And look – it’s whole, and soaring.