More than just care for children

Tucked in a corner of the Lady Ridgeway Hospital (LRH) for Children in Colombo is a room with brightly-coloured pictures on the wall. A beautiful kingfisher, frogs, dogs, houses and children adorn the walls, along with a height-measuring tool.

The 'yardsticks' of a diet

In and out go parents carrying babes in arms, holding on tightly to toddlers or accompanied by older children.

It is a busy Monday at the fledgling Endocrine and Diabetes Unit and each and every one is listened to patiently, some sent for blood tests, others guided to an adjoining room for their weight to be measured and still others told to get admitted to hospital for further tests. Several leave with boxes of pens, not the writing kind, of course, but the insulin-injecting type.

Care and kindness mixed with practical advice are all-pervasive and it is obvious that lots of time is spent on explaining to both parents and children how to deal with their ailments.

This unit, opened in August 2013, has been of immense service to the children of Sri Lanka referred by Paediatricians from across the country or the LRH Outpatients Department itself and caters to those between the ages of 0 and 16 years.

'Weighed' down with a smile. Pix by Amila Gamage

It functions under Consultant Paediatric Endocrinologist, Dr. Navoda Atapattu, who is the very first to be trained in this sub-speciality in this country.

The importance of this unit which deals with major common conditions such as diabetes, thyroid issues, growth disorders, pubertal disorders and obesity as well as some rare syndromes may be assessed by the numbers who have accessed its services.

Last year (2014) alone on the registers of the unit are 108 children with diabetes, 840 with endocrine disorders and 100 with hypothyroidism, while 110 have been guided away from obesity.

Although actual numbers are not known, the magnitude of the problem of childhood diabetes is highlighted by the fact that just into the second month of 2015, the unit registered the 16th child with this condition.

“Many children with these conditions need to be followed-up in a separate clinic, as special attention has to be paid to minute details,” explains Dr. Atapattu.

Dr. Atapattu and her two Medical Officers spend a lot of time with their little patients and their parents making them understand the condition they have and how to deal with it in their daily lives.

There is definitely an increase in diabetes but the prevalence rate is not known, she concedes, explaining that she is hoping to coordinate with Endocrinologists dealing with adults to carry out a survey to find the numbers.

Getting down to disease details, Dr. Atapattu points out that childhood diabetes falls into two groups – Type 1 which is believed to be due to

genetics and the environment and is treated with insulin injections and Type 2 caused by obesity which is managed with tablets.

Dr. Navoda Atapattu advises a young mother

There seems to be an increasing tendency towards Type 1, the reason for which is unknown and Dr. Atapattu has secured special funding to provide these patients with insulin pens, glucometers and strips all free of charge to take home with them to control this condition.

Once these insulin pens are issued to patients, there is scrupulous follow-up. They have to call the doctors of the unit regularly, until their next visit, seeking immediate advice if the sugar levels fall or rise.

Once referred to the unit initially, the patients would be registered and all tests and investigations done free of charge. The samples are tested by the Medical Research Institute. Thereafter the insulin pens etc would be given and the only cost the patients’ families would incur is the needles for the pens.

Dr. Atapattu, a mother herself and “who is on the side of children”, gives practical and doable advice to parents of her little diabetic patients.

“We have to change their mindset because they come with set ideas. One child had been given mung (green gram) for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Another child was hitting out at his mother because there were so many dietary restrictions,” she says, adding that at the unit they advise parents not to give pure sweets such as toffees, but allow the child a specific amount of a ‘sweet item’ such as a piece of chocolate, a scoop of ice-cream or a piece of cake soon after lunch. Once it is allowed with a main meal, they also advise that the child be sent out to play to ‘burn’ it up.

With the recommendation that the child should be discouraged from snacking in-between meals, they are also told how to adjust the insulin amount that is injected once the child has had a sweet item.

The cooperation from the children is amazing, MediScene understands. When everything is not a ‘don’t’ and they are given sweet items on a regulated basis, whatever they get from outside such as party-bags they bring back home and hand over to their parents without eating them on the sly.

Some of the early signs of childhood diabetes are increasing thirst, weight-loss and bed-wetting which starts all of a sudden, according to Dr. Atapattu.

An anxious mother carrying a baby walks in during the interview and Dr. Atapattu studies the exercise book in which all the details are meticulously entered. “Baya wenna epa,” she tells the mother, assuring that there is nothing to worry, after checking the blood test report.

It is not the case with a young mother from Embilipitiya whom Dr. Atapattu urges admission to do a battery of tests, for her baby has been diagnosed with Down’s Syndrome. “The mother is only 23 years old and we need to screen her whether it is genetic as other children she may have could also be born with Down’s Syndrome,” she explains.

She reverts to our interview and talks of obesity among children. A majority of the children with obesity she is looking after are not rich. In around 90%, obesity is not due to junk food but rice and curry. Rice is good but not in a large quantity, she reiterates, pointing out that the portion size these children have been eating is huge.

When they come to her, the question she asks is how many cups of rice they eat. Sometimes the answers leave her startled. One child had been eating 15 cups of rice per day.

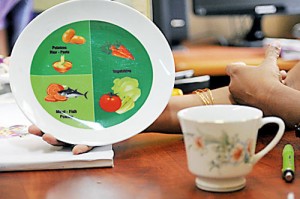

Some mothers say “tikkak kanne” but for Dr. Atapattu the ‘yardstick’ lies on the window-ledge by her table. It is a tea-cup. The other is a coloured plate with clearly demarcated areas – half for vegetables, quarter for carbohydrates and the other quarter for fish or meat. Bowls of rice are certainly a “no, no”.

Along with the right diet, there is also dished out advice on healthy living, MediScene understands.

Dealing with ‘short stature’ in children, this Consultant says that when they are referred to her unit they exclude other factors such as diet and medications which could be instrumental for the condition. Thereafter, a hormonal test is carried out and if a deficiency is identified, the child is given growth hormone therapy.

She pays tribute to her mentor, Prof. Shamya de Silva, due to whose influence when she was a House Officer Dr. Atapattu went in the direction of the sub-speciality of endocrinology, who had also initiated growth hormone therapy.

“Girls with short stature need to come early so that we can treat them,” urges Dr. Atapattu, explaining that they need to rule out Turner Syndrome and look into delayed puberty. The first sign of short stature would be the child not being the same height as her peers in Grade 1. Even before that at the well-baby clinic, the early signs would manifest when the child’s growth is plotted by the midwife.

A different side of the same coin would be early attainment of puberty (before the child reaches eight years). Even in this situation, when parents notice breast development in a small girl, they need to seek medical help, without awaiting total puberty which would be too late to address it.

Early attainment of puberty needs to be arrested with medications after proper testing, as otherwise there would also be growth stunting. A different angle of the same issue is that such children could also be more vulnerable to abuse as they are very young but developed sexually, it is learnt.

In boys, if there is appearance of pubic hair before they are eight years old, it would be time to see a doctor, says Dr. Atapattu, explaining that in the case of boys early puberty could be due to a pituitary tumour while in 90% of girls the cause is not known.

Attaining puberty late – 13 years for girls and 14 years for boys — should also be checked out. It could be that it runs in the family or some other reason such as genetics, a pituitary tumour or chronic illness. However, an evaluation is essential.

Many boys come with delayed puberty rather than early puberty, it is learnt.