A view from within

Earlier this year, activists from the Cinema for Peace Foundation thought smuggling copies of ‘The Interview’ into North Korea via hydrogen balloon was a good idea. Adam Johnson doesn’t agree. The author is not against smuggling things in, in principle. He’d just rather the activists choose a different film.In the now widely criticised Hollywood comedy, Dictator Kim Jong-un is the target of an assassination by bumbling journalists. “I’m really afraid of a movie that mocks them, that is a satire,” Johnson now says quietly. “If you could give the North Koreans one thing would it be The Interview? There are some Americans who think they’re a joke and there are a lot of other Americans who really care – I know who I would like them to meet first.”

Adam Johnson

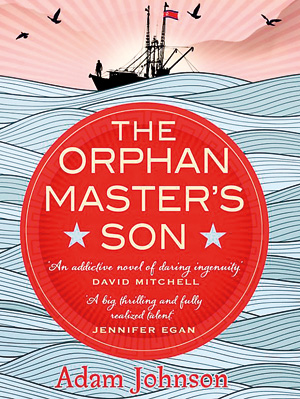

Johnson’s opinion on the issue is one worth hearing. The author of the Pulitzer Prize winning ‘The Orphan Master’s Son’ he is, after a fashion, an expert on the country. To write the novel, Johnson lived, breathed and dreamed North Korea for years – spending his mornings reading propaganda newspapers, listening to enough Sanjo music that he discovered a taste for it, and poring over every account, map, satellite photo and report he could find of what life was like in one of the most mysterious countries on Earth.“I was a crazy obsessive,” he says, frankly.

A big, earnest man, Johnson keeps his head shaved and his tone mild. He towers above the crowd at the Zee Jaipur Literary Festival. He did the same in North Korea, and yet the two experiences couldn’t be more dissimilar. He remembers the deeply surreal experience of walking among thousands of people in the streets of Pyongyang and seeing that the men all had the same haircut and wore identical pairs of blue shoes. The women wore the exact same shade of lipstick. If he was unnerved by his hosts, they were equally unnerved by him. “I did ask questions that seemed to be deeply troubling to them. I said ‘Where are all the handicapped people? I said ‘Where are the mailboxes?’ He recalls visiting a Buddhist monastery and coming away convinced that all the monks were actually actors.

If it were the case, it would be far from the strangest thing to happen in North Korea. Johnson captures some of this in his novel, which tells the story of Park Jun Do, an orphan raised to thrive in darkness. At age 14, Jun Do is crouching in the tunnels that run deep under South Korea, and when he emerges it is to explore other kinds of darkness – as a kidnapper for the government, as the signaller aboard a Korean vessel, as a minor diplomat who actually visits the US. Many adventures later, a fall from grace brings terrible repercussions, and then in Part II of the book, our character re-emerges. He is perilously close to the centre of all power, and as the action builds to a crescendo, it is fitting that the risk he takes, he takes for love.

“The biggest lie in the book is that one character would see everything my character sees,” Johnson tells the Sunday Times. In fact, he is philosophical about the limits of his knowledge. “The book was the best I could do,” he says. Most North Koreans live fairly normal lives,” he adds, “If they follow the rules, they get their meagre portions. They have their families. Those aren’t the people who defect, so we don’t hear their stories. We only hear from the people who take the biggest risks and carry out to us the darkest stories, so it’s skewed.”

“The biggest lie in the book is that one character would see everything my character sees,” Johnson tells the Sunday Times. In fact, he is philosophical about the limits of his knowledge. “The book was the best I could do,” he says. Most North Koreans live fairly normal lives,” he adds, “If they follow the rules, they get their meagre portions. They have their families. Those aren’t the people who defect, so we don’t hear their stories. We only hear from the people who take the biggest risks and carry out to us the darkest stories, so it’s skewed.”

Johnson was even forced to tone down his depictions of the ‘Dear Leader.’ When Kim Jong Il died before the book was released, the author was pleasantly surprised to find interest in the late dictator was greater than ever. “I wanted to make him real though, not a monster but a human being.” Johnson had heard for instance the stories of a chef who had lived with Kim Jong Il on and off for nearly two decades. “Apparently he was impish and whimsical and loved to drink and loved endless parties…he had a sense of humour.”

There are however other segments and portrayals that are nearly entirely accurate. Johnson chose to write sections of the book in the voice of propaganda – which North Koreans reportedly have piped into their homes by the State. “One of the things that turned me from a reader into a writer was propaganda,” says Johnson who discovered that great propaganda always incorporates a kernel of truth. Koreans newspapers would make hay with facts about child hunger in America, homeless people on the streets or even fires due to shoddy construction work. “Part of getting North Korea right is criticising America,” says Johnson who confesses that he found much to criticise about his homeland.

While literature on nuclear threats and geopolitical manoeuvring was abundant, Johnson wrote the book he wanted to read, one which answered for him the questions that he was most interested in – what was it like to fall in love, to be married, to have a child, in a society so constrained? It was also important to him that even where there seemed little cause for optimism, his was a story underlain with hope. “It can be grim,” he says, “but the book also has love and self-definition and growing personalisation of an individual.” In the end, it’s what makes ‘The Orphan Master’s Son’ perhaps more worthy contraband for the helium balloons to carry in to Pyongyang.