Columns

Highway to information and diplomatic roadblocks

View(s):So the much-wanted Right to Information (R2I) draft bill that was to be presented to parliament on February 20 got stuck somewhere before it could reach that hallowed assembly at Diyawanna Oya.

It was the new Media Ministry secretary who said the draft bill would be tabled in parliament on that date. Now it has been pushed back to March, or as Public Administration Minister Karu Jayasuriya told a meeting last week to discuss the issue, it will see daylight before parliament is dissolved in April.

It was only a few days earlier that the Friday Forum while welcoming the Government’s move to go ahead with an R2I law was lamenting the administration’s reluctance to make draft bills more freely available so as to permit more informed and productive public debates. The Forum referred to the Government’s intention to discuss in the next few days the R2I legislation with “stakeholders” (doubtless and NGO coinage!).

There is an old saying about carts and horses. This surely is a case of putting the cart before the ass. If the draft bill was intended to be tabled in parliament on February 20 then it would not be wrong to assume that it had already been discussed with relevant sections of the community before the bill was finalised.

But last week Public Administration Minister Jayasuriya speaking on the subject with some civil society groups is reported to have said his ministry along with the Justice Ministry and the Media Ministry “would be involved in drafting the Act”. He is said to have been “addressing a stakeholder consultation…. where non-governmental organisations, academics, lawyers and journalists gave their views on the Act”.

Even Alice would surely have found these happenings were becoming curiouser and curiouser. If Minister Jayasuriya has been correctly reported — and I have no doubt he was — then how could they still be discussing with relevant groups the draft a bill that according to earlier reports from the Media Ministry was to be in parliament on February 20.

If it is only now that Minister Jayasuriya, the last person who tried to push through an access to information bill that was roundly rejected by the previous administration, is talking to civil society organisations and other appropriate groups, who were the persons in the committee that the secretary to the Media Ministry said earlier had looked at earlier draft bills and the current draft and apparently approved it?

To any normal individual this would surely seem a case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand intended to do. Or is one ministry trying to score points over another as being the prime mover of an important piece of legislation. Such things have happened before.

To any normal individual this would surely seem a case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand intended to do. Or is one ministry trying to score points over another as being the prime mover of an important piece of legislation. Such things have happened before.

It is because the draft bill as circulated appeared to be lacking some essentials and unclear that I asked last week who was responsible for giving the green light to what one assumed was the final draft of the bill to be present to parliament last month.

In this column last Sunday I specifically asked why the names of those appointed to this committee along with their affiliations had not been made public. Surely this is what one expects from an administration dedicated to transparency and accountability as publicly avowed. Especially so when the subject is one that appears to be handled — some might say manhandled — by a ministry that should be particularly committed to providing information to the public without one having to seek it.

Instead one has had little information on who sat on this committee, except that officials of the Attorney General’s Department and the Justice Ministry would be involved.

Now when it is reported that “stakeholders” had consultations with Minister Jayasuriya last week one has the legitimate right to ask who sat on that original committee and why those organisations and individuals who were belatedly consulted last week had been ignored or neglected on a subject so important that some countries have constitutionally guaranteed the right to access information. It would surely be ironic if access to this information on the Right to Information Bill is denied or is not made available, to put it charitably, to the public.

There already seems to be some public disillusionment with the present administration, possibly because the community expected it to perform miracles within a short time. The “rainbow-coloured” Government is partly to blame because it had raised the aspirational levels of the people, some of whom expected to find a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

On top of that is the belief in some circles that important sections in the Government have created a new-fangled nepotism under which only those who attended a particular Colombo school cherry-picked for official positions whether this has to do flying high or managing things on the ground.

This jobs for the boys approach hardly dove-tails with what the public have come to expect from promises of yahapalanaya in its broadest sense. Similar criticisms are already haunting British Prime Minister David Cameron who, to the chagrin of Conservative Party backbenchers and supporters outside, is seen to be packing his Cabinet or important offices with former Etonian contemporaries or other public school toffs who, it is said, have little or no familiarity with party members or supporters at grass roots level.

But let that pass for the moment. My concern is the scope of the R2I legislation. It would seem, at first glance at least, that its provisions apply to public ‘institutions’ that provide public services to the community in Sri Lanka. That naturally includes all state ministries and departments.

But what of state institutions that are located outside Sri Lanka. I refer in particular to our diplomatic missions. Since the law would apply to the Foreign Ministry, by extension it should apply to our diplomatic missions.

If that is correct, and it certainly should be so, how will this impact on, firstly, foreign journalists who seek information from our missions and secondly Sri Lankan citizens living abroad.

If the right to information is only extended to Sri Lankans, then would foreign journalistshave no right to information irrespective of whether they are seeking innocuous information or seeking answers to searching questions?

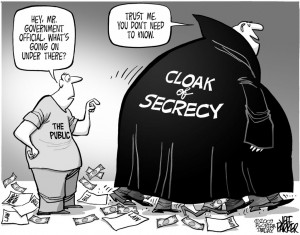

Cartoon courtesy Florida Today

What if the inquirers are Sri Lankan journalists living abroad or Sri Lankans in general?

Surely under the law they cannot be denied information unless they are treading on forbidden territory as specified in the law. But my own experience in having been in the diplomatic circuit for 50 years, both as a journalist covering diplomatic affairs in Sri Lankan and elsewhere and briefly as a diplomat, is that our missions are loathe to provide information unless it happens to be of little or no importance or they are seeking publicity.

But can accredited journalists genuinely seeking information in pursuit of their professional requirements be fobbed off as often happens in our missions? Take a simple case. A few weeks ago Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera was in London for a couple of days on his way to Washington and New York.

During his stay in London he met Foreign Office Minister overseeing Sri Lanka Hugo Swire. The Sri Lanka High Commission in London seemed to want to downplay this visit and the official position of the high commission was that it was a private visit.

The high commission might even have denied the minister was here had it not been for the fact that Sri Lankanwebsites reported it and there was also a photograph of Swire and Samaraweera shaking hands on the steps of No 10 Downing Street.

Now, one does not have to be endowed with Socratic wisdom to know that no photographs are taken outside the Prime Minister’s Office, especially of officials shaking hands, if this was a private visit.

But the high commission was trying to get away with an explanation which to any seasoned person who had also seen the photograph, which was untrue to say the least. It is not only accredited journalists but any Sri Lankan citizen would have the right to know whether the minister was in London and if so the purpose of his visit under provisions of the new bill.

The question for the drafters of this bill and for the Foreign Ministry is whether our diplomatic missions are excluded from the provisions of this bill and whether these missions maintained at tax payers’ money can refuse to provide information or tamper with the truth without suffering the consequences that other officials would have to.

If diplomatic missions prevaricate or procrastinate, one alternative would be bombard the mission with daily queries on information, whether that in information is important or not. One of the failures of our diplomats is they often try to hide information or divert attention without engaging with the media to our advantage.

Leave a Reply

Post Comment