Sunday Times 2

India’s Daughter: Dare ban these men and their mindset?

The year was 2005. A cub reporter then, I was returning after interviewing a politician in Lutyen’s Delhi. It was getting late, 9 to be precise, and with no auto in sight, I and the photographer decided to flag a passing chartered bus. As I stepped on the bus, I saw there were just four men on it. Before the photographer could board, the driver suddenly accelerated. Scared out of my wits, I just jumped off. The bus didn’t stop but the raucous laughter of people on the bus still rings in my ears.

Probably every woman in India has faced that fear and much worse, and the impotent anger that comes with it. Seven years later, I could still feel the terror of that moment as I read about the Delhi Braveheart. She could not escape her brutal tormentors, but even as she died in a Singapore hospital, she lit a flame. And that’s the reason why India’s Daughter needs to be watched – to ensure the debate and public discourse her death inflamed should continue.

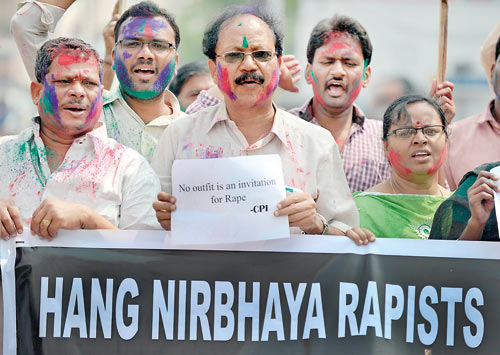

Today is International Women’s Day - Activists of the Communists Party of India(CPI) hold placards during their protest against the rapists of Delhi student, Nirbhaya, in Hyderabad on March 6

The film — which documents the brutal gang-rape of a 23-year-old physiotherapy student in December 2012 that galvanised the nation — has been blocked after a court injunction was secured. A “stunned” home minister also promised action against the documentary by Leslee Udwin even as BBC4 brought forward the film’s telecast. The film has also been uploaded on YouTube.

It will be watched – as every banned film is. The film chills you and makes you tear up all over again as the Braveheart’s parents talk about their extraordinary daughter and the golden future which awaited her. We have seen them on our TV screens as the case unfolded but this time, they are talking about those little details which make the humdrum real life.

Her punishing 18 to 20-hour workday where she used to attend medical school during the day and work at night at a call centre to ramp up her family’s meager income. Her request to her mother that she wants to go and watch Life of Pi before her internship started the next day. The family which celebrated their daughter as much as their sons and even sold off their land to ensure she realised her dream of becoming a doctor. Their shared dream of a good future which they had almost realised before it was so cruelly snatched away. “Akhri baar jab hum usse hospital me mile to usne haath mein haath liya, chuma or bola, ‘sorry mummy, humne apko bahut takleef diya (When we met her last at the hospital, she held my hand and said, ‘sorry muumy, I have given you a lot of trouble),” says her crying mother about the Braveheart’s last moments.

The general public is aware of what the unrepentant Mukesh Singh, one of the prime accused in the case, said in the documentary but it was the lawyers of the accused who really frighten you. All of them reportedly pin it on the victim – how she overstepped her limits by going out late in the evening accompanied by a boy who was not a blood relative.

One of the defence lawyers, ML Sharma, reportedly says that India has the best culture and there is no place in it for friendship between men and women. He also goes on to say how in India, women are not allowed to go outside after 7 or 8. He likens women to flowers which are worshipped when in temple but are spoiled in a gutter.

Another defence lawyer AP Singh echoes his sentiments and adds if a girl has to go out, she should go out only with their relatives and not boyfriend. He is the same man who had earlier said he would set his daughter/sister on fire if she had a premarital relationship.

This is a theme which is echoed over and over again during the documentary — it was not a rape, it was a lesson taught for stepping outside the confines of ‘Indian culture’. The accused, the lawyer even their families repeat that women should dress, behave, act in a certain way and stay in the confines of home. And if they step out, they are answerable for all that ensues.

“She went out to watch a film with a friend. Is that a crime?” asks the Braveheart’s tutor. In India, apparently, it is. This refusal of the Indian society to accept the new, emancipated woman is the subtext that drives this insightful documentary. A long list of experts discuss how rapes, acid attacks, domestic and sexual violence is the result of an India caught between modernity and tradition, patriarchy and the new woman who is breaching the narrow boundaries the society has made for her.

The focus is as much on showing how the accused are the products of their environment – a slum in Delhi where amidst poverty and violence, patriarchy is at its strongest.

The accused thought they had shamed the couple enough. They probably never thought the case will even reach the police. So, despite the deep social chasm that separates them, the way those five men thought is no different from the bizarre comments people in power have expressed about rape victims.

Ironically, this was the case that started the process of shredding that veil of shame. It started that chilly December two years ago when India came out and demanded that women be treated as equals and justice must be delivered. And that debate needs, no asks, to be taken forward because there is no other alternative if we want India’s daughters to be respected.

| ‘Everyone should watch the film’ The father of the victim, who died of injuries sustained during the shocking attack, said on Thursday he thought everyone should watch the documentary, which showed “the bitter truth” about attitudes to women in India. “Everyone should watch the film,” news channel NDTV quoted him as saying on its website. “If a man can speak like that in jail, imagine what he would say if he was walking free.” The victim’s mother told NDTV she did not object to the ban but believed Singh’s views were widespread in India. “I don’t care what the government does, bans the film, doesn’t ban the film, the only thing I know is that nobody is afraid,” she said.

A necessary spotlight The crime was exceptionally shocking, but it grew out of a misogyny that is all too common. As much as the harrowing details of the gang rape and murder of Jyoti Singh, it was the sense that this horror was animated by attitudes that condemn many Indian women to lesser indignities and injuries every day that brought vast crowds on to the streets. The film, India’s Daughter, trains an unflinching eye on the evil deeds of one day in December 2012, but its real service is in exposing wider prejudices. By going to the courts to stop it being shown, the Indian authorities reveal themselves to be unable – or unwilling – to grasp the connection between the two. The immediate controversy surrounded the death-row interview that director Leslee Udwin conducted with Mukesh Singh, the rapist who drove the bus on which Ms Singh was assaulted. It is, of course, chilling to hear him argue that “you can’t clap with one hand”, that a girl who steps out after dark is “more responsible” for rape than a man. But more frightening than the vicious self-justification of this lowlife are the arguments with which the defence lawyers attempt to woo wider society. A 23-year-old medical student’s life had been brutally cut short after a trip to the cinema, and yet ML Sharma felt it appropriate to liken women to flowers, beauties which ought to be worshipped in temples, but which would, inevitably, degrade if they sank into the gutter. “In our culture,” he added, “there is no place for women.” Another lawyer, AP Singh, observed that, if his own daughter dabbled in pre-marital relations, he “would put petrol on her and set her alight”. The words of these two educated men cannot and must not be taken as speaking for India as a whole. The world’s largest democracy affords some women prominent roles, and indeed produced one of the first female prime ministers. But Ms Singh’s parents say something revealing when they recall how friends were mystified when they celebrated Jyoti’s birth “as if she were a boy”, the same something that’s borne out in the large male majority among Indian infants, a gender gap in which selective abortion and even infanticide have surely played a part. Some of the remarks that Ms Udwin coaxes out of Mukesh Singh may be rare, but his claim that “housekeeping and housework are for girls” is one part of his worldview that is anything but unique. The Indian police, at the presumed behest of the government, sought to get the film blocked on account of Ms Udwin’s supposed failure to follow certain bureaucratic procedures regarding the prison interviews, and because to broadcast the words of a notorious rapist could be inflammatory. When Ms Singh’s family were closely involved with the film, to get hung up on either point seems perverse; it would make more sense if the real source of the objection was patriotic resentment at foreign film-makers shining an unflattering light on Indian society. But uncomfortable or not, it is a light that had to be shone. The BBC deserves credit for defying demands made in Delhi and bringing forward this urgent broadcast. - Courtesy the Guardian, UK |