Lanka’s moment of crystal glory

View(s):Richard Boyle uncovers the little known saga of how George Keyt and L.T.P. Manjusri

figured in a major international exhibition in 1956 in a medium unfamiliar to them

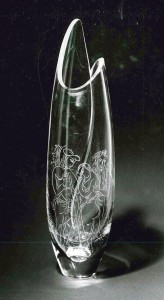

After many years I encountered a copy of the beautifully illustrated exhibition catalogue, Asian Artists in Crystal: Designs by Contemporary Asian Artists Engraved on Steuben Crystal, published by Steuben Glass, New York (1956). It is of significance in the history of Sri Lanka’s visual arts because George Keyt and L.T.P. Manjusri each contributed one design for this, to them, unknown medium: Keyt later experimented with a design for stained glass.

George Keyt’s ‘The Bodhisattva Vessantara gives away his wife’ and (inset) the artist as portrayed in the catalogue of the exhibition, ‘Asian Artists in Crystal: Designs by Contemporary Asian Artists Engraved on Steuben Crystal’

In the catalogue these memorable artists are profiled in a full page, and the work which represents their art in the exhibition is reproduced on the facing page. This catalogue is handsomely presented, with decorative endpapers and culturally representative drawings that divide the 36 artists into regions of Far East (China, Japan, Korea, Philippines), Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma), India and Ceylon, the Middle East (Pakistan, Iraq, Iran), and the Near East (Syria, Turkey, Egypt).

I remembered this catalogue well, as I had used it for research purposes in writing the script for the documentary George Keyt’s Life of the Buddha (1987), directed by Sharmini Boyle, with the painter and art historian Albert Dharmasiri as production consultant. In the film, Keyt explains his renowned murals at the Gothami Vihara, Borella.

The Introduction to the catalogue reveals that from January 18 to February 19, 1956, an exhibition created by the American company, Steuben Glass, titled “Asian Artists in Crystal”, was held first at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and subsequently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from March 9 to April 8. The exhibition was also held at the Corning Museum of Glass from May 30 to September 23, 1956.

A portrayal of the exhibition I found online is a black-and-white 17-minute film titled Asian Artists in Crystal, produced by the Thomas Craven Film Corporation for the United States Information Service (USIS) in 1956. There are brief explanations of the designs, but no mention of the artists.

“Great traditions

carried forward”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art produced a leaflet in addition to the catalogue in which the president of Steuben Glass wrote of the exhibition’s primary purpose: “To exhibit publicly, to the people of the world, examples of the creative art of modern Asia as appreciated and interpreted by America.

“For too long the West has tended to judge Asian art chiefly by its magnificent historical manifestations. It is inspiring to know that great traditions are being carried forward by contemporary artists, working in more modern style and more modern media. This present manifestation of Asian culture is coincident with national independence and progress. The drawings that these Asian artists have prepared for Steuben Glass show, in the radiant medium of glass, an astonishing variety of themes and styles.

“Glassmaking is a collaborative effort. In each completed piece are incorporated the decorative drawing of the artist, the subtle shape devised by the glass designer, and the skill of the glass blower and the glass engraver. All who have worked together on this project can share a common pride.”

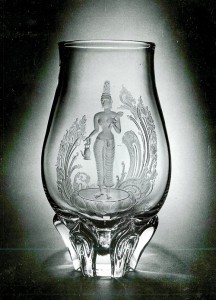

L.T.P. Manjusri’s ‘The Goddess Tara’ and (inset above) the artist as portrayed in the catalogue of the exhibition, ‘Asian Artists in Crystal: Designs by Contemporary Asian Artists Engraved on Steuben Crystal’

From June 25, 1957, to June 10, 1958, the exhibition toured the home countries of the participating artists under the auspices of the USIS, opening in Seoul and ending in Cairo, with Colombo in-between. For this tour additional editions of the catalogue were issued in Arabic (Beirut), and English/Arabic (Egypt, by USIS Cairo, on behalf of the Société des Amis de l’Art). Copies of the original catalogue were available for the exhibition in Colombo.

Steuben Glass was an art glass manufacturer founded in 1903 in Corning, New York, by Frederick Carder, an experienced glass designer, and Thomas Hawkes, owner of the cut-glass firm, Corning Glass Works. Steuben produced glass in 7,000 shapes and 140 colours until World War One. But wartime restrictions made it impossible for Steuben to acquire the materials needed to continue manufacture and the company was consequently sold to Corning Glass Works.

A major change in management occurred in 1932 as the Great Depression hampered the sale of Steuben and there occurred a dwindling interest in coloured glass. So Steuben started to produce colourless art glass and the artistic direction shifted towards modern forms. In addition, the company developed a clear glass that had a very high refraction index (how light spreads through the medium), which enhanced the fluid designs.

The project “Asian Artists in Crystal” began in 1954, when, searching for new production designs, Steuben sent Karl Kup, the curator of prints at the New York Public Library, on a two-year trip throughout Asia. His task was to commission a single drawing from artists of his choice. When complete, the 36 drawings were transposed to a variety of glass objects and engraved by American craftsmen. The drawings, later presented to the New York Public Library where they remain, were included in the exhibition. Rejected drawings, which may be of interest, are also housed at the library.

A duplicate set of the drawings was shown at the Corning Glass Center; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Marshall Field and Co., Chicago; Gump’s in San Francisco; and other stores carrying Steuben Glass. Thus Keyt and Manjusri received lengthy exposure of their work in America, though limited in content.

“The art of the East and the craftsmanship of the West”

In the catalogue’s Foreword, David Finley, Director, National Gallery of Art, and James Rorimer, Director, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, state: “The collection Asian Artists in Crystal is a felicitous combination of the art of the East and the craftsmanship of the West. Here is yet another proof that art knows no boundaries and that culture is one of the strongest links between civilized men.” According to Finley and Rorimer, “Friendly understanding and common interest completed this unique project.”

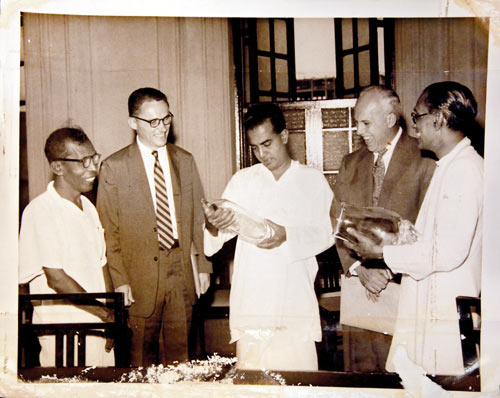

The artist Manjusri (far left) with Minister Kalugalle (centre) and Prime Minister SWRD Bandaranaike (right) admiring the works

- The artist Manjusri (far left) with Minister Kalugalle (centre) and Prime Minister SWRD Bandaranaike (right) admiring the works

In the introductory “The Drawings”, Karl Kup relates how he received messages of support before he began his quest: “’The war brought great stress to the arts in Korea, but our artists have never stopped painting and sketching,’ read a message from Seoul; and Colombo assured us that an art festival, coinciding with the visit [either in 1954 or ’55], should not only produce drawings of significance but open arms of welcome to the Steuben project.”

Which art festival Kup refers to is uncertain, but this period was when the 43 Group was at the height of its fame and popularity, and Keyt and Manjusri were both members of it, so perhaps the festival was related to this leading post-Second World War, post-colonial art movement.

Kup asserts that Eastern artistic convention, though inspired, has blinkered cosmopolitan awareness: “Steeped in the tradition of their own countries and beliefs, most Asian artists have but little knowledge and understanding of the arts of the West. Their paintings, their

American craftsmen work on the vases, faithfully following the artists’ designs (above and below)

drawings, their sculpture quite naturally follow established cycles of subject matter; their manner of rendering is indigenous, almost intuitive.”

“It may suggest the murals of

Ajanta and Sigiriya”

“As I proceeded towards Thailand, Burma, India and Ceylon, I found religion, Buddhist and Hindu, to be the mainspring of inspiration.” This was true regarding both designs from Ceylon. Keyt’s “The Bodhisattva Vishvantara Gives Away His Wife”, reproduced on a stunning narrow, elliptical vase, 17 inches (43cm) tall, was declared by Kup to be “drawn in bold and liquid lines, monumental in its sparseness of detail. It may suggest the murals of Ajanta and Sigiriya and the lessons taught by Cézanne and Picasso, but the student of Buddhism in Ceylon will recognize the artist’s intention of keeping his brush free from outside influence.

“Aware of the decaying past, urged by humanist aspirations, George Keyt has developed technique after technique, and has now become one of the giants of Asia. Speaking of his design for glass engraving, he said: ‘An artist is a true member of society only if he can adapt his art to the need of his fellow man.’”

In Religions of South Asia: An Introduction (2006), edited by Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby, the actions of the Bodhisattva Vishvantara are explained: “One of the most well-known Jataka tales, at least in Sinhala tradition, tells the story of the Bodhisattva in his penultimate life, when he was born a prince destined to become a king. In this particular tale, “Vessantara [Vishvantara] Jātaka”, the Bodhisattva gives away everything that is his – including his wife and children – in order to perfect the virtue of selfless giving.”

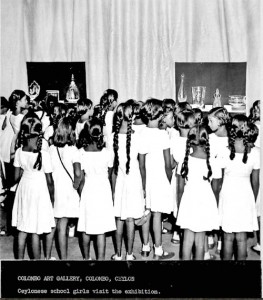

Snapshot from the past: Schoolgirls of Ceylon view the exhibits when the exhibition was brought to the Colombo Art Gallery

Manjusri contributed “The Goddess Tara”, reproduced on a deep, broad vase with lotus base, 12 inches (30cm) tall. The catalogue states: “The Goddess Tara is the offspring of the tears of Avalokiteśvara, shed for the miseries of the world. The Bodhisattva of the Mahayana pantheon, passing like an archangel from the remote heavens where the Buddha lived to the world of men, gave birth to Tara to protect mankind.

“In the design of Tara with her ornamental accessories, the artist has emphasized the harmony between the goddess and nature, the lotus in her [left] hand being a symbol of her divinity [there is a kettle of water in her right hand]. Erect and vigilant she stands, as in early bas-reliefs and temple sculpture; as dignified as her bronze prototype, made in the 10th century.”

Goddess Tara’s right hand is in the gesture of vara mudra or “gesture of charity” and her left hand in vitarka mudra, “gesture of debate”. The marked contrast of the slender waist with the heavy breasts and hips is the ideal of feminine beauty. “The goddess, dignified and graceful in this manifestation, represents the chastity and virtue and the embodiment of love, compassion, and mercy.”

“A millennium of patina had been scrubbed away”

The prototype bronze statue of Tara alluded to (dated to the 7th or 8th century CE, not the 10th century as stated by Kup), was unearthed between Trincomalee and Batticaloa in 1830. Its height is 57 inches (144cm). Governor Brownrigg ‘gifted’ the statue to the British Museum in the year of its discovery.

In 2010 the statue was placed in the section “Inside the palace: secrets at court (700–950CE)” of A History of the World in 100 Objects, listed chronologically as No. 54. A joint project of BBC Radio 4 and the British Museum, it comprised a 100-part series that used ancient art, industry and technology as an introduction to human history from two million years ago to the present.

The exhibits on display at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC: January 18- February 19, 1956

A copy of the statue is on display at the National Museum, Colombo. Hopefully one day the original will be returned. As a contributor to lakdiv.org/tara remarks: “On a recent visit [to the British Museum] in 2000 I saw that it had been polished. Does the Museum have the moral authority to continue to keep this treasure which was stolen from Lanka during British Colonial rule? When I spoke with the National Museum in Colombo they had no knowledge that the statue had been polished, and a millennium of patina had been scrubbed away from the goddess without consultation.”

Discoveries at the Museum

and Archives

The catalogue provides much information but of course there are no post-American exhibition details such as: Where are the objects kept? When was the exhibition held in Colombo? Were there reviews? What further information is available? Thus began a quest in which Ismeth Raheem, as he often does, played a vital role. He did remember visiting the exhibition in Colombo at the National Art Gallery, but was unsure if it was in 1957 or 1958.

Surprisingly, there is little or no reference to Keyt’s or Manjusri’s experience with the “Asian Artists in Crystal” exhibition in biographical writing about them. Why that is remains obscure, especially as this outstanding, internationally-acclaimed exhibition came to Colombo. Furthermore, as Ismeth confirmed, the National Museum houses on the Upper Floor the Keyt and Manjusri pieces, which were gifted to the nation in 1959.

From the National Archives Ismeth discovered that the exhibition was held at the National Gallery from September 16 to 28, 1957. There was an approximate attendance of 25,000 according to Steuben. ‘N.W.’ gives a review of the exhibition in the Ceylon Daily News of September 18, 1957, accompanied by a photograph of D.C.R. Gunawardene, Secretary to the Ministry of Local Government and Cultural Affairs and U.S. diplomat Henry T. Smith inspecting an exhibit.

“We, in Ceylon,” writes ‘N.W.’, “are placed in an embarrassing position which requires us to recognise the craftsmanship of the Steuben Crystal workers and at the same time remember the reputation of the Sinhalese craftsmen of the 5th century, who, according to Emerson Tennent received the homage of the Chinese as the finest crystal engravers of the time.

“I know that the memory, even though vaguely recalled by historians, of our heritage, is rather a wry and sentimental sort of memory; albeit, the fact that this collection contains two designs by Ceylonese artists is a matter of great satisfaction; even if the craft is only a recollection for us. It is a singularly graceful tribute to our artists.”

‘N.W’ continues by quoting from something other than the catalogue regarding how the designs were incorporated in the crystal: “’Asian Artists in Crystal’ is a new experiment in plastic art, and this single occasion brings together the designs of several Asian artists. These designs, necessarily sharp, near black-and-white drawings, have been traced photographically, to reduce or enlarge the original design.

“The form each crystal is to take having been decided upon, the craftsmen of Steuben Glass copy each design in red paint, freehand, upon the bowl before the final engraving is made direct upon the crystal.” The engraving for both pieces was designed by one of Steuben’s finest, Don Pollard. “His major engraved works represent some of our best-known achievements,” declares a former Steuben chairman.

From Corning Museum to Sunnylands

Regan Brumagen of the Rakow Research Library at the Corning Museum of Glass informed me, “We don’t own the glass objects for this series, although we do have photographs of the objects and the drawings”. Regan advised me that the Annenberg Foundation Trust – Walter Annenberg was a respected American publisher, philanthropist and diplomat – has a full set of the 36 crystal objects at Sunnylands Estate, California.

Moreover, she believed an exhibition of “Asian Artists in Crystal” was to be held there. This was confirmed by Frank Lopez, the Librarian and Archivist of Sunnylands Estate, who advised me the event was due to begin in January 2016 and last a full year: “This will mark the 60th anniversary of the series and we felt it was appropriate to re-introduce the public to these important crystal pieces.”

Frank told me of his visit to the library in May 2014 to view the original drawings. “We are under discussion to obtain digital prints with the plan of displaying them and also printing them in our catalogue.”

He was also able to tell us that Steuben originally produced not one but two copies of the 36 works. One set was exhibited at the National Gallery of Art (Jan-Feb 1956) and then at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (March-April 1956). The Government purchased the set and under the auspices of the USIS sent it on a two-year tour to countries represented in the series.

In a privately issued compilation from Steuben to Ambassador Annenberg there is information regarding the country presentation. “On August 13, 1959, R. Burr Smith, U.S. Chargé d’Affaires ad interim, presented to Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike” the Keyt and Manjusri engravings “for the permanent collection of the Government College of Fine Arts.” At some point, it is said, the college loaned the pieces to the museum for an exhibition, since when they have remained there.

“The other set,” Frank continues, “was retained by Steuben Glass and featured in various exhibitions. Eventually this set found its way into Steuben showrooms and individually sold to institutions and collectors. Any piece in the series could be specially made to order.”

The sources of the Sunnylands collection, Frank explains, date back to 1971, when “Ambassador Annenberg was offered 13 pieces from set 2 and the other 23 pieces could be made within a 14-16 month period. He decided to purchase the entire set (13 from set 2 and 23 made to order pieces). The works we have by Keyt and Manjusri are not from the original 2 sets but made to order.”

Anyone heading for California or residing there in 2016 should view the exhibition in the splendid setting of Sunnylands. The 36 pieces as a whole are of obvious significance as an expression of post-World War Two, post-colonial Asian art in predominantly traditional form; an expression admittedly moulded to some extent by Kup’s choices.

For Sri Lankans, attention must be focused on the made-to-order works of art by two of Sri Lanka’s most distinguished modern artists in a design-form they had never attempted before; viewed in circumstances far removed from the Colombo Museum.

Postscript: George Keyt and Stained Glass

As mentioned earlier, Keyt had an experience with stained glass, as recounted to its conclusion by Tissa Devendra in the second of two articles, “Keyt in Montreal”, The Sunday Times, April 17, 2011. Tissa wrote of “the rediscovery of the ‘lost’ stained glass panels based on his [Keyt’s] stupendous canvas ‘Lanka Matha’ commissioned for the Ceylon Pavilion at the Expo 1967 in Montreal, Canada”.

Transporting the delicate panels to Colombo became a problem, so Ceylon relinquished a modern artistic masterpiece, for the government gifted it to the City of Montreal. “After spending some years in storage, the cultural authorities in Montreal have installed the panels, beautifully back lit, in the foyer of the Bibliothèque [Library] Marie-Uguay,” Tissa comments.

Following the publication of the first article, Tissa was contacted by Paul Hogan, a relation of two craftsmen at the Whitefriars Stained Glass Factory, London, who created the stained glass panels from a canvas painting by Keyt. Considering its importance as a centre for the history of glassware, it’s not surprising that, as with the Steuben engravings, the Corning Museum plays a role in the telling of this related story.

Hogan discovered Corning has a photograph of Keyt’s painting. A study of it “shows us that the installation in Montreal lacks the two end panels. In all their glory panels of a brilliant sun and a silvery moon frame the statuesque Lanka Matha.” The original painting was found at the Sapumal Foundation, Colombo.