Sunday Times 2

Sudhu Veddho

View(s):How Sinhala showed up arbitrary class-and-classroom differences in a heavily mixed minority.

Stephen Prins writes

SINHALA – the Written Language and the Literature – was a lot like SIGIRIYA. That is to say, the Language and the iconic Rock posed a similar challenge to the imagination – that of mighty, near unscalable difficulty. Difficult, that is, if you were in your exam-taking mid-teens and spoke Sinhala second to English. To our great shame, we could barely read and write the language, or decipher a Sinhala movie poster.

We considered both Language and symbolic Sigiriya as related; indigenous outcrops, sprung from the same Mother Soil. From afar, both were daunting. And, in our narrow view of the bigger picture, Language and Rock seemed to have been willfully placed to obstruct a certain language-paved path to the future – the future for a small segment of the population, that is. If you couldn’t master the Language, you had no territorial right to the Rock, and the rest that went with the Rock.

That is how the language issue appeared to us back in 1967. The message sent out was clear: if we could not handle the language, we had no place in the system. Fair enough.

By “we”, we mean the 36 largely laidback English-stream students of a respected boys’ school in an especially leafy part of the city. There we were, poised, with uncertainty, to take the General Certificate of Examinations, Ordinary Level that year. The one subject few of us had hopes of passing was Sinhala. That conclusion came early, at the beginning of the year, when our Sinhala Master, the redoubtable Mr. Cantrose, took charge.

The first day Mr. Cantrose walked into class, he looked around in much the way a Sergeant Major might survey a bunch of straggly, sorry-looking recruits – with clear distaste.

What he saw ranged in rows before him was a gallery of motley, acne-mottled faces, all reflecting a remarkably diversified national demographic, the outcome of centuries of invasive alien forces entering the country. To Mr. Cantrose’s critical eye, the class itself had an invasive look, as if the 36 of us had slipped in through a campus back door.

You couldn’t blame him. If you had stood in Mr. Cantrose’s shoes, you would have seen a somewhat complacent set of coddled, well-fed faces, most of them from privileged backgrounds.

We were a confluence of bloodlines, and we looked variegated. Complexions went from tea, coffee, and cocoa – with or without cream – to milk, curdled. We were Sinhala, Tamil, Moor, Portuguese, Dutch, Eurasian, German, Jewish, Malay, Borah, Memon, and Chinese. Our colourful miscegenation set us apart from the relatively consistent-looking Sinhala and Tamil streams in the adjoining classrooms.

When the Sinhala Master – and he was truly a Master of Sinhala – walked into the class that first day, we saw at least one thing in common: like us, Mr. Cantrose was mixed. His father was a Scottish planter, we were told, and his mother a country lady from Gampola. He came from powerful pioneer stock, that band of fearless souls whose destiny it was to open up new frontiers, hew out colonial habitats, subdue subordinate lives.

Mr. Cantrose was a wholly impressive personage. He was over six feet tall, with broad shoulders, and long arms. He had a healthy hue, pink to tanned, and he looked the robust Scout and Drill Master he additionally was. His roar of a voice was effective out in fields and playgrounds and trebly so in an enclosed classroom. On good days, he had a mischievous smile, as though he knew a little secret about all 36 of us, but wasn’t telling; on such days, he would be expansive and relate wonderful stories, the kind that kept Boy Scouts enthralled around a camp fire. The stories were about history, myth, travel, geography and ghosts. On a bad day, the story would be about us – the 36 brats from English-speaking homes who hardly deserved the good things we had.

Mr. Cantrose had a powerfully structured head, somewhat equine, and an exceptionally high forehead. Looking at his head alone, rising high above the teacher’s desk, you sensed a formidable intellect.

As a Sinhala scholar of a superior order, Mr. Cantrose was entirely wasted on us. He should have been lecturing at institutions of higher learning, not barking at a bunch of gaping, gap-teethed Form Fivers. He and we knew he was casting pearl before swine.

Very early in the year, Mr. Cantrose very clearly gave up on us. We were a lost cause. He told us so. He predicted Sinhala failure for most of us, but heroically he plodded on.

What kept up his interest during those two hours a week of instruction was not the class but the Texts. You could feel his relish in the rules of Sinhala Grammar, the shapes and sounds and echoes of the Vocabulary.

The prescribed texts that O’ Level year were a tough Sinhala primer, pitched at least at university level, a book of “kavi” (poems), and two “nava katha” (novels).

Chalk & Cheese

The strange part of it all was the obvious disconnect between the O’ Level Syllabus and the O’ Level Exam Paper, both prepared by the inscrutable Department of Examinations. They were two different things, not remotely related; the syllabus was so much chalk, the exam a platter of strong-smelling cheese. The unexplained disparity seemed not to bother Mr. Cantrose, who dutifully powered his way through the required texts till the end of the year. It was up to us to find our way. No wonder we looked the way we did – first lost, then desperate.

There were two Sinhala papers, A, for those who used Sinhala as a first language, and the much easier B, for those who used it as a second, third or seventh language.

The rants

Quite apart from our piteous state as students of Sinhala, there must have been something else, something overtly irritating, about the class to trigger the explosions of bad temper and the periodic rants Mr. Cantrose was prone to.

One afternoon, out of the blue, he went for our parents, specifically fathers — those who drove around town in fancy cars and drew five-star salaries. He made his point obliquely, by way of highlighting his own humble lot. What he may not have known was that his parent stereotype was not true of all 36 of us.

“Let me tell each of you,” he thundered, “that I SWEAT FROM MY BROW AND EVERY PORE OF MY BODY FOR EVERY SINGLE CENT I EARN.”

After a volley like this, the class would collapse, like a wall of shattered glass.

Mr. Cantrose’s contempt seemed especially concentrated on a point, a circle rather, in the middle of the room.

Centrally positioned was a group that comprised Devashri Abeyewansha, Rizan Mohamed-Marikar, Krishan I. Goonagasinghe Jr, Mitch McBlair, and self. The circle radiated further, but it was this particular five that seemed to annoy Mr. Cantrose most. And he memorably singled out each of us for his scorn.

The class was ordered to write an essay on “A Day in the Life of a Farmer.” This required imagination, because the closest any of us had got to a typical country farm was a flashing view from a Jeep speeding through the highways of the Dry and Wet Zones. We started on our essay, brows furrowed like recently ploughed paddy fields.

The next day Mr. Cantrose walked in, our 36 essay books bundled under his arm like a sooty pot of half-cooked rice. He dumped the books on his table. The top of the pile held the essays he intended to shred.

First was fair Rizan Mohamed-Marikar, whose mother was English and father a scion of a famous jeweller family. “Your Sinhala has the SMELL of English to it,” Mr. Cantrose said, accusingly holding Rizan’s essay to the writer’s nose. The word “smell” was used in a way that suggested a dead rat or cat decomposing somewhere above the classroom ceiling. Double-barelled Mohamed-Marikar, it was implied, had a long way to go in deodorising his Sinhala composition skills.

Next on the hit list was the equally fair Mitch McBlair, whose father was Anglo-Indian, of Scottish extract. McBlair was a plumpish dreamy youth, always gazing out of the window. Mr. Cantrose believed he was looking in the direction of the hostel kitchen and ridiculed his affection for food. The truth was that McBlair was dreaming of the day he and his family would get on a ship and head to Australia, leaving Sinhala behind forever.

Devashri Abeyewansha, fairest of all, was third in line. No one meeting Abeyewansha for the first time would believe he was not totally Celtic or Anglo-Saxon. His maternal grandfather was Scottish, and his dignified Sinhalese father an Old Boy of the school, a Cambridge Blue, and the 79th member of the exclusive 80 Club. Abeywansha’s crime was his blatantly privileged upbringing. “You are spoilt,” Mr. Cantrose sneeringly began. “You think you can come in a grand car and do as you like here. You think your parents’ wealth will see you through. You have no interest in studies. Believe me, You Will Not Pass This Exam.” Abeywansha turned colours, from scarlet to knock-me-over-with-a-pigeon-feather pale.

Then it was the turn of Khrishan I. Goonagasinghe Jr, whose grandmother came from an English family famous for its World War I heroes and its monumental medical institutions in the UK and the US. Goonagasinghe, a talented tennis player and son of a prominent sports personality, won trophies for tennis but none for Neatness of Dress. It was his personal appearance that Mr. Cantrose unforgettably critiqued that day. “You are by far the worst dressed student I have seen in all my years as a teacher,” he began. “Your shirt and trousers are shoddy, baggy, badly cut. You look as if you and your family have never heard of a smoothing iron. You slouch and drag your feet. Your socks sag. Your shoes are scruffy. Your laces never tied.” The look on Goonagasinghe’s face was, as they say, a study.

And then Mr. Cantrose swivelled and aimed his freezing gaze in our direction. “As for this young man with the suitcase, I guarantee that if I were to open that box I will find not what should be there but a load of rubbish.”

So saying, Mr. Cantrose strode up to our desk, flipped up the lid of our battered carry-all and revealed a secret hoard of storybooks within.

It was unfortunate that in our haste to get to school that morning, we had forgotten to conceal the light reading under a layer of the heavy stuff, textbooks and the like. Storybooks we carried as comfort food for after-school consumption. It was nice to know the fun books were there, stashed away like boxes of candy. After seven hours of grey, bland classroom fare, the brain craved flavour, colour, excitement – qualities you didn’t find much of in the textbooks of our day.

Triumphant, Mr. Cantrose thrust his large hand into the suitcase and picked up a hyper-colourful bunch of detective stories, thrillers, and other weekend reading. He held up the “rubbish” for all to see. Then, one by one, the lurid paperback covers flashing guns, corpses and women in lingerie, he let the incriminating books drop like shot birds back into the suitcase.

Kiss Me, Deadly, the falling titles began.

The Female of the Species.

The Bride of Fumanchu.

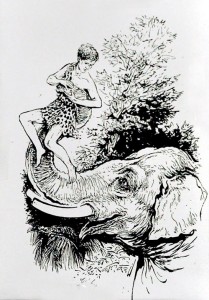

Dutch castaway Hans van der Meer and Friend: drawing by Ralph Thompson, from the novel "Wild White Boy - A Story of the Ceylon Jungle", by R. L. Spittel.

The Case of the Haunted Husband.

The Spy Who Loved Me.

Lady – Here’s Your Wreath.

As the “rubbish” fluttered and fell, something was happening within: on the outside our ears were burning; inside, rage, revenge and resolution were stirring, coagulating, coming to a boil.

That afternoon, after school – it was one of the days the Sinhala tutor came home – we informed the affable, betel-chewing, bicycle-riding Mr. Piyasoma that we were determined to pass the Sinhala B Paper at the end of the year. He beamed. “Follow my instructions and you will pass. Trust me.”

Deal made, we settled down to serious Sinhala study. We had 10 months to shape up.

Mr. Piyasoma made it clear that the Education Department’s GCE O’ Level Sinhala syllabus hadn’t the remotest relevance to Exam B Paper reality. Ignore the prescribed texts. Ignore what they teach in school. Leave all to me, he said.

Mr. Piyasoma’s prescriptionfor success lay in our mastering six model essays, a weekly vocabulary, and a close reading of a novel, “Sudhu Veddha.”

Sweet, studious revenge

Once a week we would squeeze out an essay of 150 words, the tutor would fine-tune it, and we would memorise it. One of those essays, or a variation on its theme, would turn up in the exam paper, of that you can be sure, Mr. Piyasoma said with confidence.

We would learn 10 new Sinhala words a week, and at the end of the year we wouldn’t find an unfamiliar word in the exam paper.

We read cover-to-cover a novel set in Ceylon. It was a certainty that a passage from the book would be in the vocabulary and comprehension exercises. “Sudhu Veddha” had appeared for five successive years in the Sinhala B Paper. You could bet it would be there that year too.

Sinhala was the only GCE O’ Level subject we consciously, deliberately prepared for that year. An hour or two after school with Mr. Piyasoma’s homework was de rigueur. After a couple of months, we were actually enjoying the Sinhala assignments. Mr. Piyasoma guffawed with delight. At this pace, he said, the chances of passing were fair to good.

We wrote and memorized essays on topics such as “Vinodha Gamanak” (Picnic or Pleasure Outing) and “Perani Nagarak” (Ancient City). We wrote separate accounts of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa and Sigiriya.

We byhearted multisyllabic words like “waiddhyawaraya” (doctor), “paraawarthanaya” (reflection), and “raajyawidhiwathkama” (good governance).

Reading “Sudhu Veddha”, the adventures of a shipwrecked Dutch boy growing up in the jungles of Ceylon in the era of the Kandyan Kingdom, was an outdoorsy pleasure. The white boy Hans van der Meer had the sunburn and body odours of Tarzan and Robinson Crusoe. We read the translation alongside the English original, R. L. Spittel’s “Wild White Boy.” The author, (Grand-) Uncle Dick, had given an autographed copy, dated 14.10.1958, to his sisters, Lottie and Agnes, and they had presented the book to us, their three grand-nephews. By the end of the year we had completed the novel, having gone through it sentence by sentence, back and forth between Sinhala and English.

Sinhala paper

When we sat down to take the Sinhala B Paper in December, we were one big smile. The exam was as Mr. Piyasoma had predicted, compiled as if on his instructions. Bless the Dear Man.

One of the essay topics was “A Pleasure Trip to an Ancient City.” Our composition spliced two memorized essays (four, in fact, squeezing in two extra ancient cities for good measure). The vocabulary and comprehension exercises were based on an excerpt from “Sudhu Veddha.” We were ecstatic.

When the exam results came out a few months later, in February 1968, our Simple Pass in Sinhala was all that mattered. It had the glitter of gold, a gleaming medallion in the middle of our modest O’ Level mark sheet.

By then we were settled in Form Six. The last session we had with Mr. Cantrose was in November the previous year, a week before the O’ Levels. The Teacher had done his duty by the School and the Education Department by completing the Syllabus, irrelevant as it might have been to exam actuality.

In our remaining two years of secondary school, Teacher and Student did not cross paths. If they had, one might have stopped to mention the Pass in Sinhala B, and the Other would surely have shown surprise, even amusement.

The last we heard of Mr. Cantrose was that he had retired to the mountains of his childhood, somewhere in the Kandyan Kingdom. It was rumoured that he was spending his final days in a monastery.

We pictured him seated cross-legged on a pedhura in a pirivena library, going through ola leaves and Pali-Sanskrit texts by the light of a kuppi laampuwa (oil lamp). And in the evenings, in the scented shadow of a plumeria tree, an early quarter moon sliding over a mountain crest, conversing with learned monks in Postgraduate Sinhala. A conversation our Class of ’63 could never have joined in. Not in a thousand full moons.

Postscript: It was only many years later, in the first bloom of middle age, that we finally made it to the top of Sigiriya. We were not in the best of physical form. It was an arduous climb. There are no short cuts to the top – nor to the bottom.