A real life drama that’s 150 years old

The old and the new side-by-side — the bustling ‘hub of health’ in the very heart of Colombo and the nerve-centre of the whole of Sri Lanka proudly carrying on a legacy handed down over a century and a half.

The ‘White House’ built in 1904 still exuding old-world charm had been the Administration Building not only for the General Hospital Colombo but also for others such as the De Soysa Lying-in-Hospital and the Lady Havelock Hospital (Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children). Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

It is here that the real-life dramas of life and death, joy and sorrow and tears and laughter are played out daily, as have been done for 150 years.

While the main commemoration event of the 150th anniversary of the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (NHSL) was held on Friday, March 20, with President Maithripala Sirisena as the Chief Guest, it is on Tuesday that Director Dr. Anil Jasinghe takes us on a journey down the corridors of time, sometimes a little hazy, to the very beginnings of this august institution.

The birth of the General Hospital Colombo in 1864 at its current location was as the ‘successor’ to the first civilian hospital under the charge of a single doctor in British Ceylon back in 1861 down Prince Street in the Pettah, the details of which are obscured by the sands of time.

NHSL Director Dr. Anil Jasinghe

Juxtaposing the then and the now, Dr. Jasinghe uncovers how that 100-bed hospital has now metamorphosed into a 3,404-bed institution, with the Outpatient Department (OPD) and clinics alone drawing as many as 5,000 people daily. While this is the workplace of more than 7,000 staff including doctors, nurses, para-medics, administration and minor staff, the recurrent (running) expenditure of the NHSL is a mind-boggling Rs. 5 to 6 billion per year.

“More than 30,000 people congregate in this area daily,” says Dr. Jasinghe, explaining that a study by the University of Moratuwa has found that this huge crowd includes health personnel, patients, visitors and even passers-by who stop awhile to take in the frenetic activity. But how many

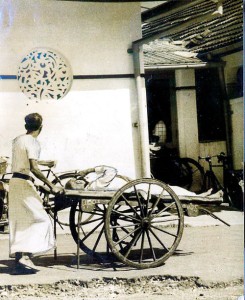

Photo from the past: A patient being taken on a trolley near the OPD

let their minds dwell on this institution which has been an inextricable part of the lives of millions of people scattered around the country, not only in times of peace but also in times of war?

As ambulances with whining-sirens and flashing-red lights rush critically-ill patients from the remotest corners of the country to this centre of health excellence, we become privy to an unseen side of this institution.

The file with regard to the Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamin bin Hamad Al Thani, who was on a four-hour visit to Colombo, is on Dr. Jasinghe’s table on Tuesday and he explains that the NHSL is responsible for the medical care of each and every VVIP including national leaders and celebrities who visit the country. “Although the VVIPs will come with their own medical team, we have the facilities ready in case of an emergency, with a room in the Merchants’ Ward vacant as well as relevant staff on the alert. We also provide the medical escort,” he says.

Leaving the present behind, for the Sunday Times team, the leisurely walk back into the past begins at the original gate on Kynsey Road, opposite the landmark clock tower of the Medical Faculty, which had given entry to the sprawling General Hospital premises in the days of yore.

This is after we have picked the brains not only of Dr. Jasinghe and Nursing Officer Nilanthika Withanage of the Quality Management Unit who is in the process of compiling the history of the hospital but also Dr. Joe Fernando who took up the onerous task of running the General Hospital as its first Superintendent after it became an independent entity freed from the ‘Colombo Group of Hospitals’ in the 1970s due to its size and importance.

The first heart operation at the General Hospital Colombo performed by Cardiothoracic Surgeon Dr. A.T.S. Paul

With the demand for health services growing, the Colonial Government had sought to move its Prince Street hospital to a location with space aplenty in 1864. The re-location choice was a 32-acre kurunduwatte (cinnamon land) in the ‘countryside’ of Longdon Place, away from the residential areas of Mutwal and Mattakkuliya, we learn.

It is during Governor Henry Ward’s period (1855-1860) that plans had been drawn up and

£ 3,000, a princely sum at that time, earmarked for the hospital.

What did the area look like, we wonder? A snapshot of those times is created in ‘A History of Medicine in Sri Lanka’ authored by Chest Physician Dr. Chris Uragoda, who quotes a description of the location of the General Hospital by Dr. Andreas Nell who was born the year that the hospital was opened.

The first permanent building in the premises: The Victoria Memorial Eye Ward

“The General Hospital was built in a not-too-populated neighbourhood of the city. Approaching from the north, was a leafy lane behind Tichborne Hall and The Gatharium, two large residences in Maradana. From the east, there was a similar lane from the Welikada jail, on which among the very few other houses were two rival establishments providing coffins. From the west, Turret Road, one saw where the Eye Hospital now stands another small low-built bungalow which was called the Mango Lodge. This was used by the later Dutch Governors as a hunting lodge. From the right, along Regent Street there were only five houses. Leaving the hospital southwards was a long avenue to the cemetery at Kanatte. When naming this street in Colombo, this avenue was called Kynsey Road after Sir William Kynsey, Head of the Medical Department.”

The walkabout of the Sunday Times which begins at the sturdy gates on Kynsey Road, past the Blood Bank to our right brings into view the imposing but beautiful two-storey ‘White House’. Built in 1904 at an estimated cost of Rs. 124,744.75, the ‘White House’ still exudes an old world charm, with its square exterior and towering frontis-piece and interior replete with intricate teak timber-work. Looking up from the ground floor, the designs on the roof are visible even today with two staircases made of timber leading to the upper-floor.

The Franciscan nursing nuns ministering to patients

The ‘fire-resisting’, heavy-duty, locked and barred built-in safes of the ‘White House’ believed to be the first administration building give a clue to how much value the British placed on safeguarding documents not only of the General Hospital Colombo but also those of De Soysa Lying-in-Hospital and Lady Havelock Hospital (now Lady Ridgeway Hospital). The ‘White House’ is now the home of the Skin Clinic.

Onto its left is the current radiology unit which is thought to be the first OPD set up in 1910, while to the extreme left is the Gnanasekeram-Skinner Paying Ward, currently Ward 16 housing neurology patients. Close-by are both the Merchants’ Ward and the Sailors’ Ward.

One needs only to close the eyes for a moment to relive the picture of tranquillity that the Professor of Surgery in the University of Chicago and Surgeon General of Illinois, Nicholas Senn had described back in 1905 on a visit here, as quoted in ‘A History of Medicine in Sri Lanka’.

“The hospital is made up of numerous one-storey brick-and-mortar pavilions connected by roofed colonnade, cemented walks which impart to the whole complex of buildings a fine architectural appearance. The snow-white walls and pillars and the red tile roofs are in strong and beautiful contrast with the perennial green surrounding the building inside and outside of the large square court which they enclose.”

Across the hospital, we walk to the tiny cross-shaped St. Peter’s Chapel tucked into a corner of the premises, where people would have knelt in prayer, like they still do, for blessings to be received and blessings already received.

Here lodged the Franciscan nursing nuns after their arrival at the General Hospital on June 22, 1886, when the British requested their help through the Vicar General of Colombo, Fr. Joseph Boisseau. In a tiny room of their home within the hospital, the first holy mass had been held on June 24, with the chapel coming up on April 1, 1887 and till today draws a motley crowd for its noon mass.

Back then the nuns were acting as the Florence Nightingales of the hospital while priests of the order of the Oblate of Mary Immaculate were the chaplains and drew the comment, “it is a mission within a mission” from the first Archbishop of Colombo, Christopher Bonjean. According to records, when these ministering angels of the sick left St. Peter’s House in 1964, their numbers had been as large as 81.

Commenting on the early times, Dr. Joe Fernando says that the GHC was the first to deploy female nurses, initially British nurses from the United Kingdom. A qualified matron from there had also been sent to establish a Nursing School within the hospital.

With difficulties in recruiting locals as nurses, the Colonial Government had appealed to the Catholic Church for help and the first batch of nuns from the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary had taken over the nursing of the 200 patients.

Nursing Officer Nilanthika Withanage

A shortage of beds at the General Hospital, meanwhile, had led to an annex being opened at Ragama for the elderly and the chronically-ill, with the Franciscan nuns working there as well, it is learnt.

However, Dr. Fernando points out that an outbreak of cholera in 1912 at the Ragama quarantine camp had compelled the patients who were sent to Ragama from the General Hospital being brought back. “This is why even to this day the medical wards of the General Hospital are referred to as the Ragama section.”

A stone’s throw from the chapel, is also the Pathum Bodhiya, which according to Ms. Withanage, from what people say has also been there a long time, where the relatives of patients seek solace.

Our journey ends at the dull red and yellow Victoria Memorial Eye Ward built in 1903, in keeping with Hindu-Saracen architecture and Ms. Withanage points out that this is believed to be the first permanent building on the premises.

The suggestion that it should be built to commemorate Queen Victoria had come from none other than the Governor’s wife, Lady Ridgeway. With a fund being set up to help those with eye ailments, philanthropist Muhandiram N.S. Fernando had donated Rs. 5,000 while appeals through the newspapers had been able to raise Rs. 100,000 from the public.

Designed by popular British architect Edward Skinner and constructed at an estimated cost of Rs. 160,000, the building with a commanding view of Lipton’s Circus has walls of 200’ in length and 97’ in breadth at the front. Two portraits that are said to have adorned the area close to the elevator, those of Queen Victoria and major donor Fernando, are no more.

Now this building put up at Lady Ridgeway’s urgings is benefiting vascular and transplant patients as well as those with orthopaedic problems.

As we wind up our tour of the olden-day landmarks of the NHSL, Dr. Jasinghe’s assurance keeps echoing. While he has a vision to establish a vibrant ‘National Health Square’ encompassing all heath-care institutions in the area, Dr. Jasinghe also hopes to bring to life the grandeur of the past by resurrecting the original facades.

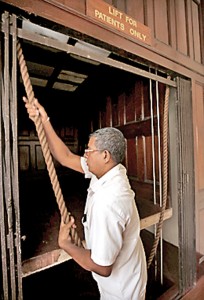

| A gem of a ward A gem of a relict is the Merchants’ Ward built nearly a hundred years ago in memory of William Henry Figg whose generosity had ensured its existence. Not only intact is the lift drawn up and down by a thick rope manually, staff members standing-by on the ground and upper floors, when a patient has to be transferred up or down but also the beautiful wooden staircase rising past a stained-glass window.

|