News

To sink or swim with Colombo Port City?

The Colombo Port City Development has been in the limelight during the past three months. A range of articles has been published by organisations, environmentalists, politicians, social media groups, the developer/investor and others associated with the developer on engineering and environmental studies. The involvement of wider segments of society in these discussions indicates the perceived importance of the project.

In the presentation of diverse views, however, certain salient facts were found to be either deliberately or unintentionally omitted or misrepresented. Due to this distortion, it is apparent that the public is confused about the real situation of the project and its impact on the country.

They came, they bid, and made a mess of it: Possible environmental impacts ignored and laws not followed in the execution of the Colombo Port City project , investigations show

This article briefly assesses the process followed with respect to the Port City Project. It identifies deficiencies (as perceived rationally by the writer) and suggests a way forward. It does not comment on how beneficial or disadvantageous the contractual conditions in the agreement between the Chinese developer and the Government (Ministry of Port and Highways) are, as the writer is not qualified to make such analysis. However, if any such contractual condition intervenes with technical and environmental aspects, such occurrences will be highlighted. An attempt has been made to present true facts to the maximum possible, supported by documentary evidence. There could still be gaps or uncertainties, mainly due to the non-availability or inaccessibility of certain project information.

It shall be noted at the outset that this article does not intend to blame anyone for the mistakes or oversights, but to objectively identify them (thus, learning a lesson for managing similar situations in the future) and to propose a way forward, while keeping the interests of our country as foremost.

It also does not look critically upon Chinese investment. China has stood by Sri Lanka in the most critical hours of need, in addition to providing financial assistance towards many major infrastructure development projects. Nevertheless, this does not deter in bringing the public’s focus on the wrongdoings of any party, irrespective of nationality.

After searching through all available information, it was not possible for the writer to find an approved project feasibility study for the proposed Port City Development. It is indeed very surprising, yet true, that the Government of Sri Lanka has gone ahead with a US$ 1.35 billion mega project without a comprehensive project feasibility study encompassing technical, socio-economic, environmental, and financial aspects of the proposed development.

Such a study would have identified alternative development concepts and implementation arrangements such as whether it should be full-scale development or one that is phased-out. It would have considered the project’s socio-economic benefits and impacts on the country at large, as well as financial returns. It would have explored the potential land use plan and environmental concerns associated with alternative development concepts. It would also have projected the utilisation level of the country’s natural and other resources and looked into the required upgrading of existing utility services.

The original proposal to create a Port City was made in 2004. A plan for a Western Region Megapolis produced by a Sri Lankan team with the Singaporean company CESMA included it as part of Colombo city development. It pointed out that, by upgrading land in such a manner—after the urban infrastructure elsewhere in Colombo was improved—market prices would rise to sufficiently high levels to justify the cost of reclamation. It recommended filling only in the area impacted due to the construction of the South Harbour breakwater. It suggested a systematic city development process owned by the country, with a much smaller scale of sea reclamation subjected to thorough and comprehensive study.

In 2010, it appears a few senior professionals in their individual capacities had done an Initial Technical Pre-Feasibility Study. It focused on a small-scale development of 200 acres, or about 80 hectares, as had been initially planned. It narrowly addressed breakwater layouts and cross-sections (mainly as a learning step from Colombo South Port Development). It looked at wave conditions, floated ideas for protection of reclaimed areas, gave preliminary construction estimates and suggested a way forward. The report is neither comprehensive nor relevant in the context of the current proposed scale of development. It could rather be considered as a “concept note”.

The other available document is the developer’s project proposal, prepared in October 2012 and submitted to the Board of Investment with an application for BOI status. It focuses purely on the developer’s interests, his return on investment, marketing prospective, funding arrangements, etc. The report does not address the project feasibility at all. Hence, the project has moved to construction phase without knowing its technical, financial or socio-economic viability.

A popular argument from some of the supporters of the project is that the South Port Development is of similar scale, or larger, when compared with the proposed Port City development. If the South Port Development is acceptable to the country, they assert, there is no reason for so much resistance to the Port City Development.

A clear and simple counter-argument is that the South Port Development was done after a comprehensive feasibility study, encompassing all the aspects described above. The best possible technical option was selected. A phased-out development was proposed, based on demand forecast as well as material and financial requirements. An ad hoc development like Port City Development cannot be compared to a properly conceived South Port Development.

A question that often comes up is: “Is Port City bad for the country?” The most direct answer to that is: “Do not know”. Since there is no feasibility study exploring its benefits to the country, and its socio-economic impacts, it is not known whether the Port City is good or bad for Sri Lanka.

An offshore development could be beneficial to a country like ours, provided proper process is followed and an appropriate, sustainable scale identified through a comprehensive feasibility study. Some available information indicates that the present blown-up scale was decided solely to achieve the expected return on the investment for investor/developer, and not on any other country-specific criteria.

To date, the quantity of natural resources to be consumed by the Port City is not known. The intermediate stage involving 300 acres (120 ha) was suddenly blown up to a 575 acres or 233 hectares without any assessment of the availability of natural resources, mainly sand and quarry material. A lesser known fact is that, although the Port City is set to be 233 hectares in size, the extent of its total “footprint” is a massive 1,200 acres or 485 hectares including waterways and canals.

On the basis of available, accessible information (average reclamation height of 24 metres and surface area of 2,330,000 square metres), the writer assessed that 55-65 million cubic metres of reclamation material will be required. Since this is the net volume, and allowing for 15-25% wastage (a common practice when extracting sand from sea bed), the gross volume required will be in the range of 65-80 million cubic metres of sand.

At the time construction started, there was no infrastructure development plan in place. It is understood that a draft master plan submitted to the Urban Development Authority (UDA) in late January 2015 was returned to the developer for further improvement.

The developer has widely claimed that 83,000 employment opportunities were at stake in the event of the project being cancelled. It is confusing how this figure was arrived at without a project feasibility, development plan or land use plan. In the absence of substantial proof, this can only be considered a ruse.

The developer’s recent media communications argue that the Sri Lanka Government is to get 62 hectares free without spending a cent and that there should, therefore, be no objection to the project. In other words, the State and its people should be grateful to the developer for giving land free of charge without retaining the entire area.

The writer is baffled that nobody has so far publicly countered this primitive argument. Apart from using the territorial waters of Sri Lanka, the developer is extracting an unprecedented volume of the country’s natural resources to realise a poorly conceived (from Sri Lanka’s point of view) development at his own will. It looks like the project’s sudden, two-fold expansion was mainly to increase the investor’s return on investment at the expense of Sri Lanka’s environment and limited natural resources.

Both sea sand and quarry material have “opportunity costs”—an economic term meaning “value of the best opportunity foregone” and the environmental cost of the consequences. The developer has assigned scant importance to the value of these natural resources or associated environmental consequences.

The Government has offered offshore sand free-of-charge to the developer. The “royalty fee” of four per cent of market value of the sand—something any developer must incur in using the country’s limited natural resources—has been waived. This alone totals to about Rs. 10 billion for an estimated 65-80 million cubic metres of sand, at the going market rate of Rs. 10,000 per cube of sand (not counting the sand’s financial value of nearly US$ 1.7 billion).

The opportunity cost foregone by the people of this country, therefore, exceeds US$ 1.8 billion. This is more than the total investment of just US$ 1.35 billion said to have been committed by the developer. No opportunity cost has been allocated for the loss of the nearshore seabed area of 1,200 acres. While Sri Lanka gets 62 hectares, the developer gets 20 hectares on freehold basis and another 88 on a 99-year lease, totaling 108 hectares.

The opportunity cost foregone by the people of this country, therefore, exceeds US$ 1.8 billion. This is more than the total investment of just US$ 1.35 billion said to have been committed by the developer. No opportunity cost has been allocated for the loss of the nearshore seabed area of 1,200 acres. While Sri Lanka gets 62 hectares, the developer gets 20 hectares on freehold basis and another 88 on a 99-year lease, totaling 108 hectares.

On behalf of the developer, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) made initial application for the EIA to the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resources Department (CC & CRMD). The Concession Agreement places responsibility of obtaining all approvals on the SLPA.

This initial application was for the development of 300 acres (120 ha). The project involves dredging and sand extraction from burrow areas, transport to the reclamation project site, dumping at project location, construction of coastal defensive structures and spending beach, development of infrastructure including a marina.

Under environmental laws, any development within the coastal zone (2km offshore from the low water line and 300m shoreward from the high water line) is under the jurisdiction of the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resources Management Department (CC & CRMD). Any sea-based activity beyond the 2km offshore boundary is under the Central Environmental Authority (CEA). Any pollution of marine waters is monitored by the Marine Environmental Protection Authority (MEPA) which is responsible for preventing destruction of marine habitats around the country due to land or ocean based activities.

Accordingly, the CC & CRMD is the Project Approving Agency (PAA) for reclamation while offshore sand extraction from burrow (mining) areas is under the CEA. At the request of the CEA, the CC & CRMD issued Terms of Reference (TOR) for the Project EIA. In doing so, it incorporated some environmental concerns associated also with offshore sand extraction as it was logical for sand extraction and dumping on reclaimed areas to be assessed as an integrated activity.

However, the developer prepared the EIA report through his consultants in April 2011 without impact assessment on sand burrow areas. The reason could be that no burrow areas were identified at the time to meet the total requirement of filling material. Still, the CC & CRMD granted preliminary clearance subject to the condition that the developer will carry out a separate EIA study for burrow areas.

In the meantime, the developer decided to expand the project by nearly 200 percent, from 120 hectares to 233 hectares. Strangely, the developer himself (through his EIA consultant) proposed an addendum to the original EIA without receiving fresh TORs from the CC & CRMD. Thus, the addendum was drawn up on self-defined TORs by the developer, who is the project proponent, perhaps for the first time in the history of any EIA conducted in Sri Lanka for a mega project of this nature.

To backtrack, it is common practice for a PAA to let a developer submit an addendum to an approved EIA to reflect minor changes in the scope of a project. This is to save time. But this must be done through supplementary TORs issued by the PAA based on an application by the developer highlighting the change in project scope. It is not done at the will of the developer.

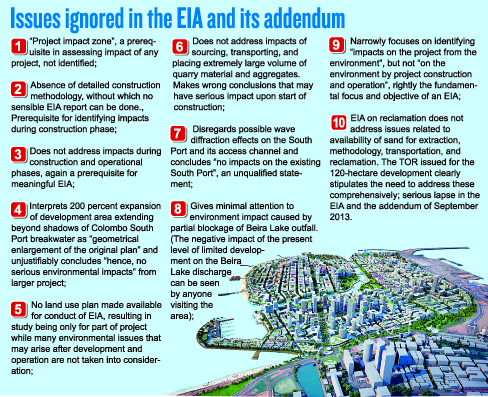

In the case of the Port City, the CEA was excluded from discussions on the addendum to the EIA. It also appears that the addendum ignores several critical and important environmental issues (see graphic).

It has been argued that any major impact not identified during the EIA process could be included in the Environment Management Plan (EMP). Although the EMP is meant to be a dynamic document that can be updated upon the identification of any new impacts during project execution, it cannot be used to cover the deficiencies of an EIA. As identified by the developer himself, the EMP is to guide implementation of mitigation measures identified during the EIA study, and to act as a tool for the management of the project’s environmental performance.

The proposed development involves both sand extraction (burrow areas) and reclamation. However, the EIA has been done treating the two as separate activities. Hence, the linkage between the two activities is lost and significant impacts could have been missed out.

The social and community consultation that should have been conducted in a project of this magnitude affecting the livelihoods of many strata of the city and suburban communities was grossly inadequate. There was no socio-economic assessment on fisheries and fishermen.

Meanwhile, in the absence of an EIA addressing offshore sand extraction and transport to project site, the CEA issued separate TORs in September 2011 for an Initial Environmental Examination (IEE). The IEE report submitted by the developer was rejected by the CEA, mainly on two grounds: a) The impact on the sensitive ecosystems including fish breeding grounds and b) the developer failure to indicate clearly the burrow areas that could fulfil total requirement of reclamation material.

The developer was advised to carry out sand exploration studies on additional potential burrow areas under the guidance of Geological Survey and Mines Bureau (GSMB), and to submit a fresh report. This is yet to be done, although the developer seems already to have extracted 8.5-10 million cubic metres of sand (based on media statements on percentage of work completed) without a permit.

The GSMB has only granted an Industrial Mining Licence (IML) for sand extraction subject to preconditions; that is, the obtaining of environmental clearance from CEA. Availability of clearance from the CEA is a prerequisite for GSMB to issue an IML as such approval must stipulate conditions of extraction based on the environmental safeguard measures spelt out in the approved EIA report.

In the first instant, therefore, the GSMB should not have issued such a “conditional IML”. Since the precondition of obtaining CEA clearance has not yet been satisfied, the licence issued, naturally, has no validity. Accordingly, any sand extraction carried out so far cannot be considered to have been done according to the legal approvals. Additionally, the developer has yet to comply with obtaining a permit from the Marine Environment Protection Agency for dumping of material into the sea as per the Marine Environment Protection (issuance of permits for dumping at sea) No.1 of 2013. This requirement was communicated to the developer in October 2013.

As the validity of both the CC & CRMD permit as well as the IML issued by the GSMB are subject to issuance of CEA clearance for the sand extraction, the project does not possess any of the valid environmental approvals to proceed.

(The writer is a Senior Consultant Engineer in Coastal and Port Engineering)

| A way forwardThe country should first decide whether it needs this kind of offshore development and, if so, the appropriate scale and timing of such development—whether it should be now or some years down the line. These decisions cannot be taken arbitrarily and will involve an element of political will as well. A comprehensive project feasibility study shall identify the sustainability as well as the economically and financially viable scale of development. This shall be followed by a comprehensive EIA with both the CC & CRMD and the CEA jointly reviewing the assessment. There are no significant issues related to the proposed location of Port City with regards to longshore sediment movement and erosion. The Colombo South Port offers partial shelter and, hence, there can be optimisation of cost on marine protective structures. With those advantages, the proposed location is suitable for a reclamation project like Port City, provided that a comprehensive feasibility confirms its sustainability. Current Project Status and violation of environment laws On March 06, 2015, the Government issued instructions to temporarily suspend the project. The developer claimed that 13 per cent of the project work was done by then. If so, it leads to multiple questions (according to photographs that appeared in social networks after a recent guided tour of the project by selected groups, the cited completion rate could be realistic). It entails 13 per cent of the total sand volume being dumped on the reclamation area. This involves a gross estimated volume of 8.5-10 million cubic metres of sand being already deposited. What is the source of this sand, when the CEA has rejected the IEE report submitted by the developer for sand extraction from identified burrow areas and the GSMB’s industrial mining licence is invalid? Does this mean the developer violated the laws of the country? It is stated that dredging was done from the access channel of the Colombo Port. If true, a separate set of issues arises: • An estimated 8.5-10 million cubic metres of sand could not be generated from maintenance dredging of the channel within five months. It would appear, then, that capital dredging (removal of large amounts of virgin material from the seabed) has been undertaken in the access channel. If it is assumed that the dredged portion of the access channel is within 2km zone, has CC & CRMD approval been obtained for capital dredging? What action has CC & CRMD taken in this respect? What is the overall impact on the access channel by excessive deepening or widening that has taken place due to excessive dredging? • It appears that, even if capital dredging is performed, such a huge volume of sand cannot come from the access channel (if it has come from the access channel, a survey would confirm the current depths and, thereby, the total volume extracted). The other possibility is that sand extraction was done from other, unknown locations. If so, which authority has granted the approval for this? In summary, the developer has violated conditions stipulated in the environmental permits issued by the respective agencies: • CC & CRMD permit, by commencing the reclamation work without obtaining environmental clearance for sand extraction from the seabed; • IML Permit issued by the GSMB, for not possessing an approved EIA for sand extraction process. It is evident that the developer has violated environmental laws of the country. Hence, the respective project approving agencies shall immediately demand clarification from the developer on those violations. If clarifications are unsatisfactory, provisions are in place to immediately revoke the issued permits, as mandated by the respective laws and as stipulated in the respective permits issued to the developer. |