Sunday Times 2

Art on an Easter afternoon

Easter afternoon 1989. The festive breakfast and lunch accomplished, we are dozing off on a chair on the veranda, an open book resting on a plumped out belly, when the bell rings. We are on holiday, and reluctant to do anything but eat, drink, sleep. Drowsy and weighed down, we are in no fit state to receive visitors. We make our way to the gate.

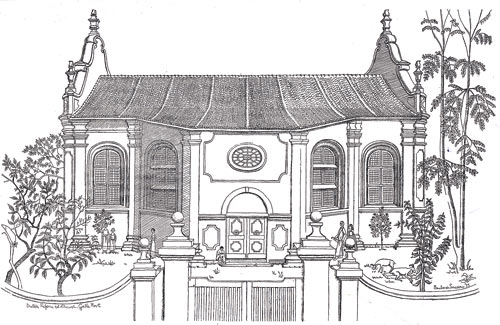

DUTCH CHURCH IN GALLE FORT, pen and ink, by Barbara Sansoni

The caller is a very young Dominic Sansoni, full of energy and enthusiasm. The talented photographer has come to greet us, and take us to his home He insists we join him “for just an hour.” There are “two people” who wish to meet us, he says. What he means is that he wishes to introduce us to two people he is keen we meet. Young Mr. Sansoni is a charmer and it is hard to resist any invitation he offers. He walks into our sitting room and picks a framed picture off the wall. “Please, let me have this, just for a week. I must have it, but just for a week.”

The framed picture is a wholly amateurish black-ink drawing done many years back, when we were just out of school. It was one of a series of drawings done out of impulse. Something we had seen in the Daily News had prompted us to grab a nibbed pen with a very sharp point, dip it in a bottle of blackest Indian ink, and scratch anything that came to mind and hand on a sheet of cloud-white sheet of paper. What we had seen in the Daily News was a pen-and-ink drawing of the old Dutch Church inside the Galle Fort. The illustration was reproduced to accompany a review of a book of architectural drawings by local artist Barbara Sansoni.

The picture was mesmerising. It was a stylised rendering of the church and its garden. The curvate stones and tiles and dipping walls were enchanting. Even the trees in the garden had an air of unreality. This was not like any church drawing we had seen. We had visited the church a couple of times, and loved it for its Dutch atmosphere and as the setting of marriages, christenings and burials of direct ancestors in Dutch times.

Laki Senanayake, artist and sculptor

We spent a long time looking at the drawing of the church. The book from which it was taken was “Viharas and Verandas,” a collaboration between artist and entrepreneur Barbara Sansoni, and artist and sculptor Laki Senanayake.

Something had started stirring within, a restlessness to do something similar ourselves. We recognised the restlessness as an itch, to be satisfied only by grabbing the same or similar instruments and tools used to scratch white paper surfaces and make black telling marks.

Off we went, to Asoka Trading Company, the second-hand textbook and stationery shop on the Galle Road, in Bambalapitiya. We bought a drawing pen with a sharp nib, a bottle of Indian ink, and four sheets of A-4 paper.

We did a couple of simplistic drawings, a la mode Barbara Sansoni. We were not dissatisfied with the results, after first acknowledging that we were not artists. Pen-pushers at best. We wanted to see the drawings up on the wall. So we went back to Bambalapitiya, to the Picture Framers, and had our humble sketches framed, passé-partout style, with glass, cardboard, and black tape. We put up the pictures in the hall and called them our “Barbara Sansoni Substitutes.”

The picture Dominic Sansoni had seized and insisted on holding in custody was a very basic drawing of a spices auction hall at the bottom of Dam Street, in the Pettah.

And so we went that afternoon to the Sansoni residence, in Anderson Road.

It was Easter afternoon, but there was no sign of Easter festivity at the house. It felt like any other Sunday afternoon. There was one thing, very Christian, however, that we had noted on previous visits, and that was the presence of crosses. They were all over the house, even in the garden. These were small, chunky wooden crosses, placed over doorways, bookshelves, walls covered with paintings and drawings. Wooden crosses were also stuck outside in flowerbeds. The premises were strongly Roman Catholic, without being oppressively so.

Seated on the veranda, working, were Barbara Sansoni and Laki Senanayake. This was our first formal introduction to the two artists, and it was an honour to be in their presence. Dominic Sansoni held up the black-and-white Dam Street drawing and the two artists smiled, politely. He said he would hang it up with other artwork in the drawing room. We were honoured, naturally.

Barbara Sansoni and Laki Senanayake had both worked on the “Viharas and Verandas” portfolio. She has described him as the “happiest of sketching companions.” They are partners in art, their mutual love for capturing beauty in line and form having brought them together on a thousand such art-filled days.

That afternoon, Barbara Sansoni was working at a small table on a coloured design of geometric shapes. Laki Senanayake was sitting at another small table, working through layers of pencilled foliage. Conversation was conducted as the art unfolded, spectacled gazes rising occasionally as the artists paused to change a pen, sharpen a pencil.

It was a slow afternoon, sunny and quiet but for bird calls. Sipping ginger beer, we thought how relaxing it is to watch artists noiselessly at work. Unlike music and dance, art – drawing and painting on canvas or paper – is a silent, quasi-spiritual activity, soundless as a temple flower making a picture of itself as it breaks off a branch, sifts through scented air, settles on grass.

Late afternoon tree shadows were stretched across the lawn. The white yellow light in the open veranda was deepening into shades of mauve. It was time to go.

Barbara Sansoni looked up and smiled. She waved a hand. Her son read the gesture, went inside, and came out with a gift. It was a copy of “Viharas and Verandas,” something we had long and longingly wanted to possess. The artist opened the large, horizontal book with its thambili-orange fabric cover and embossed title. Inside, she wrote in graceful lines of black ink: “From one linesman to another. Barbara Sansoni. 26 March 1989.”

A most substantial gift it was, infinitely outweighing our temporary loan of a small, square, thinly limned auction house in the Pettah.

- STEPHEN PRINS