Sunday Times 2

The adventure of the blue Easter egg

Crosses dominate Holy Week. The icon sacred to Christianity has been standing especially tall these days, the week of the Crucifixion, Burial and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, founder of the Christian faith. Easter is the climax of Holy Week, and Holy Week is the culmination of the 40 days of the Lenten season, a time of sacrifice and restrained living, recalling the 40 days Christ spent in the desert, seeking answers, enduring deprivation, and fighting off temptation from the Devil.

Covering the last mortal days of Christ, Holy Week starts with Palm Sunday and leads up to Christ’s last meal with his disciples, recalled on Maundy Thursday; his Death on the Cross, remembered on Good Friday, his three days of Entombment, represented by Holy Saturday, and his Rising from the Dead, celebrated today, the Feast of Easter.

The crosses begin to proliferate on Palm Sunday. Churchgoers take home blessed coconut palm leaves and weave the tender green fronds into crosses to place over doorways and next to sacred icons. The fresh crosses replace the brown, year-old palm crosses of the previous year.

The pre-midnight service that leads into Easter is profoundly symbolic; it is dramatic and thrilling, if those are appropriate words to describe moments of church liturgy. Church lights are dimmed to darkness. Outside, under the portal, coconut shells are burnt for the incense burners; the priest, in white-and-gold vestments, holds up the Paschal Candle and intones the solemn words, “Christ yesterday and today, the Beginning and the End, the Alpha and the Omega. All time belongs to him and all the ages. To him be glory and power through every age and forever. Amen.”

Candles in hand, all re-enter the church, which gradually fills with light as the candles are lit, taper upon taper. As the celebrant priest and the procession approach the altar, moving from Darkness to Light, Death to Resurrection, all the lights come on in a halleluiah of brightness and brilliance.

The Holy Saturday service leading into Easter is symbolic of moving from darkness to light, from death to everlasting life. Photo: The Guardian

Our family, Roman Catholic on Mother’s side, Church of England on Father’s, followed closely the practices of the Lenten season, from its inception on Ash Wednesday 40 days earlier. The 40 days of doing with less and doing without were enforced by Mother with the firmness of any responsible Catholic parent. We were taken to St. Mary’s Church, Lauries Road, Bambalapitiya every day of Holy Week. On Maundy Thursday, we watched in fascination as the priests went down on their knees to wash the feet of the poor and distribute bread in memory of the Last Supper; on Good Friday, we abstained from meals, as far as we could, and wore white or black for the three-hour service in memory of the Trial and Crucifixion; and on Holy Saturday, we waited out the dark time of Christ’s three-day entombment till the dawning of Easter.

Easter is as significant a day in the Christian calendar as Christmas, the day of the birth of Christ. Many say it is the most important Christian festival.

In our home, Easter and Christmas were celebrated with like festive fervour and vigour. Mother had everything on the table, the full and fancy meals prepared in ripe, over-rich Burgher tradition. Breakfast was bacon and eggs, ham and cheese, jam and marmalade, Breudher, and lots of toast and tea, followed three hours later by a lunch of curried chicken, pickles, chutneys and savoury rice, heaped with roast cashews, sultanas, and green peas, plus pudding, followed seven hours later by a dinner of roast chicken, boiled potatoes and peas, tomato-and-cucumber salad, sliced ham, butter and more Breudher. Every dish was home-made, down to the dessert islands of mango-in-syrup nestled in vanilla ice cream. It was Christmas all over again, without the carols, the wrapped gifts and the fireworks.

Easter lunch would be a little later than usual, because we had to allow for the treats of a mid-morning visit to the home of two great-aunts.

As guests of the sisters Agnes Spittel and Lottie Jansz, who lived at No. 4, Police Park Terrace, a 20-minute walk from home, you were served the best of festive fare, and of food in general. In the 1940s, when they had retired from teaching – Lottie was on the staff for years at Bishop’s College, Colombo, and Agnes was a long-term Principal of St. Paul’s Milagiriya School for Girls – the sisters set up Cuisine Milagiriya, a cookery school, the first of its kind in Colombo.

The weekly Thursday afternoon classes were held at the Vicarage of St. Paul’s Church, Bambalapitiya, where Lottie’s husband Canon Paul Lucien Jansz was the Vicar. The cookery school was attended by members of the parish and outsiders, as well as members of the British community, including the Governor’s wife. Lady Monck-Mason Moore sought a recipe for Love Cake. The precious Galle family recipe had descended through a couple of generations, and in its evolution had gathered no less than 30 eggs per five pounds of “rich cake.” One nibble was sufficient to satisfy; a whole piece filled you; two pieces felled you. Three pieces branded you a “glutton” – you could not rise from your chair. The Love Cake of Agnes and Lottie had been refined over the years, and by 1945 had a third as many eggs, but was nonetheless knockout-delicious – and still heavily “rich.”

At the Aunts’ home, we could not appear to look overly eager at Easter or Christmas. Ours was a controlled enjoyment of the foods served, savoured politely under pleased but watchful eyes. The sisters were then in their late seventies, early eighties. The treat lasted one-and-a-half hours, from 10 to 11.30 am, with five-minute breaks to play with the dog Shep and digest the cakes, puddings, pastries. We had to be out of the house and out of the way before 12, the sister’s strictly timed lunch hour. Everything was done by the clock. There was even a bell on the table, rung to announce meal times.

When we were through, Lottie would ask how much we had enjoyed the food and drink, upon which we said, in the words they had trained us to use, “Very much, thank you, Aunty.” We would then be ordered to go to the pantry and kitchen and show our appreciation to the persons who had prepared the treats. These were the domestic helpers Mr. Lewis and Mr. John. They had learnt their cooking at the St. Paul’s Vicarage, and had assisted in the Cuisine Milagiriya classes. Canon Lucien Jansz liked his food prepared with thought and care. He would write out the day’s menu, in French, in vari-coloured inks, and the menu card would be placed in a frame on the dining table. According to Father, who was like a son to the Vicar and his wife, meals at the Vicarage were formal and relaxed – happy, chatty, deeply satisfying family experiences.

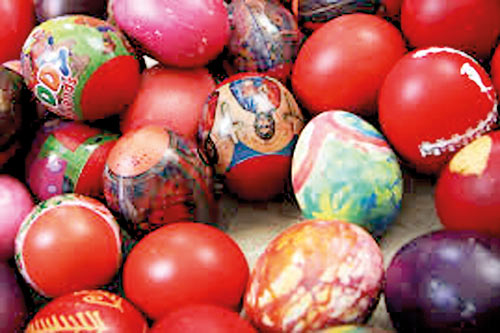

One item in the Aunts’ Easter treats intrigued Older Brother, Younger Brother and self. These were the home-made Easter Eggs, the painstaking work of Mr. Lewis and Mr. John.

The coloured eggs were contained inside real chicken egg shells that had been drained of their contents (the yolks and the whites went into the Jaggery and the Love Cakes). Through a little chipped hole in the top of the shell, you glimpsed a hard, coloured, jellied world within. The eggs came in red, orange, pink, green and blue. Each had a flavour. Red was rosewater, pink was vanilla or strawberry, green was lime or lemon, orange was orange, and blue was almond. The colours and flavours came from little labelled bottles with gold caps lined up like sentinels inside a meshed cabinet in the pantry. The jellying agent, the Aunts said, came from seaweed and moss picked up on the seashore. Who precisely went to the beach early in the morning to collect the seaweed was never made clear.

Once the shell had been peeled off, the solid egg emerged – radiant in its single-coloured translucency – firm and bouncy. Drop one on the floor and it jumped back into your hand. The eggs looked too special to eat, but eat we did, as Lottie and Agnes looked on smilingly. They told us the story of how, at the turn of the 20th century, they and their sisters and brothers, including our Grandmother, May, would walk along the beaches of Puttalam and Mannar, looking for seaweed to take home and transform into moss jelly. The great thing about gracilaria verrucosa was that it did not require an ice box to solidify.

Of the five coloured eggs, the blue was the most intriguing. Blue is not quite a natural food colour and is rarely used in cookery, except for children’s party cakes and rainbow macaroons.

As we sat in our outsize rattan chair, facing the Aunts, we held up the wobbly blue Easter egg and stared into it.

What we saw inside was the deep blue of the ocean. This was the sea that coughed up the seaweed that went into making of the moss jelly egg. We also saw, under a pale blue sky with a tiny wisp of egg-white cloud, a family of girls and boys our age, skipping along an unspoilt beach, gathering handfuls of china moss, then running inland and rustling in the poultry yard to forage for hen eggs, and saving the empty shells for later – for filling up with sweetness at Easter.

Those were happy, translucent, clear-skied times.

Unrefrigerated, unruffled, untroubled.