It’s the time of year that Seedevi gets cracking on making fire crackers

Bathed in metallic-silver dust, they look like beings from a different planet. But both K. Nirangani Fernando and her golaya are very much on earth and are in a race against time.

Labour of love: It’s a hard day’s work from morn till night, but Seedevi feels she’s fulfilling a duty. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

If not for their contribution and those of their neighbours, the Sinhala and Hindu New Year would not be what it is. For, it is from their deft hands that the harbingers of every single nekatha (auspicious time), be it for the start of the punya kalaya, nonagathe, the lighting of the hearth in the New Year, the partaking of the first meal or the fun and games after the customs and traditions have been adhered to.

Nirangani and her neighbours are licensed fire-cracker makers of Kimbulapitiya, close to Negombo, and have made it their passionate ‘business’ to bring that bang and sparkle not only to the avurudu celebrations but any festive occasion such as ringing-in the New Year at midnight on December 31 and also parties and weddings. Fire-crackers are also an integral part when announcing walkabouts by politicians and their election victories.

Thirty-year-old Nirangani, fondly referred to as Seedevi by her family, is engrossed in her work in a lean-to shed next to her home when we arrive at her doorstep. Her three sons, 14, 6 and five years old, are back from school, squabbling in the house, while her mother attempts to bring about peace and quiet.

Suddenly, the stillness of that Monday afternoon, in this village which has taken up fire-cracker manufacturing as a cottage industry, is shattered with a soooooooooo sound, lost awhile later in the skies. There is a strange lack in Kimbulapitiya – not a single mongrel, usually common in such areas, can be seen or heard.

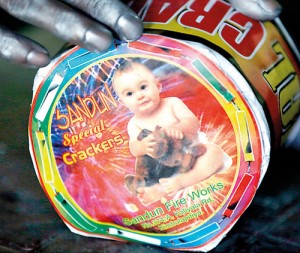

The end product bearing her son’s name on it

However, nary do the pets of Seedevi’s sons, a flock of pigeons, feeding on grain scattered on the ground, get flustered over the sound.

Seated on the floor, Seedevi’s dexterous fingers halt not, while she chats with us, telling us that the tradition of fire-cracker making has been passed down from her grandfather, to her father and now to her.

It is as a little girl that she watched with awe and excitement as her father engaged in this work that he loved. Although she has an older brother and two older sisters, “mata vitharai allala giye”, says Seedevi, explaining that in her family only she has been enticed by this craft.

Work is all-year round, buying the gun-powder (vedi beheth), a mix which includes aluminium, saltpetre or Potassium Nitrate (lunu) and sulphur (gendagam), on licence and collecting the ‘bamboos’, small tubes of rolled paper with one end of each and every ‘bamboo’ sealed with clay, from those who make them.

Seedevi and her golaya then gingerly fill each ‘bamboo’, a cracker in the making, with the ‘vedi beheth’ and insert into it the ‘vedi noola’, the thread which is lit to make the cracker go off. The preparation of the ‘vedi noola’ is of vital importance and she digresses to tell us how it is done.

Several long strands of nool are strung-up taut among the coconut trees in Seedevi’s home garden and little by little a mixture of charcoal, saltpetre and sulphur is applied along the full length of each noola and left to dry in the sun. “All this has to be done in advance and kept in stock,” she reiterates. The vedi-nool preparations go awry if the skies open up and send down showers, delaying all Seedevi’s schedules.

With a little help from her golaya the fire-cracker manufacturing line continues

Back to fire-cracker making and Seedevi details how the ‘mouths’ of the bamboos filled with vedi-beheth and stuck with the vedi-nool are tied tightly with twine and then the fire-cracker wel (chains) are separated by cutting the attached twine with a blade to make individual crackers.

“Bambuwala kata erala thibboth bok gala yanawa, hondata pipirenne ne, sadde ne,” says Seedevi, pointing out that if the bamboo mouths are not tied up securely they would be like damp squibs, going off with a mild sound without giving out the big bang expected of crackers.

Once all these labours are over, the individual fire-crackers are counted and packeted under the label of ‘Sadun’, named after one of her sons.

Her days are long and so are her nights. Waking at the crack of dawn she literally works round-the-clock till about midnight or 1 the next morning, getting only a couple of hours of shut-eye. Meals are taken on the go, because the avurudu deadline is looming and each day she strives to make at least 10,000 ‘karal’ (fire-crackers).

Two weeks before the avurudu, when we visit them, her father has already undertaken the journeys to distant places such as Anuradhapura, Gampola and Kataragama to distribute fire-crackers.

Lamenting that this year the prices of gun powder as well as ‘bamboos’ have sky-rocketed, Seedevi was working to meet set orders placed by traders who will collect the fire-crackers before the New Year.

It is when avurudu dawns that this single mother will rest awhile, taking time off her labours to spend precious time with her sons. That is until the next round of activity sends her into a spin of work like the Catherine wheels that her neighbours make.

Seedevi loves her hectic work-life. “It is a tradition of work coming down generations which I cannot let go,” she says with a smile, adding that if she does not engage in fire-cracker making it is as if she has not eaten, affecting her wellbeing.