There will never be another ‘Olu Pipila’

View(s):On the eve of Sunil Santha’s birth centenary, Dr. Tony Donaldson reflects on his enduring and endearing legacy

The first centenary of the birth of the recording artist and composer Sunil Santha will be celebrated on April 14. Born in Ja-ela in 1915, Sunil’s ambition from a young age was to be an inventor, and throughout his life he retained a passion for anything mechanical from building radios to repairing car engines.

Sunil did become an inventor, but not of rockets and engines, but an inventor of songs.

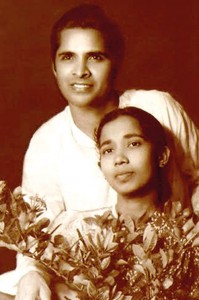

Very much a family man: Sunil with his wife Leela

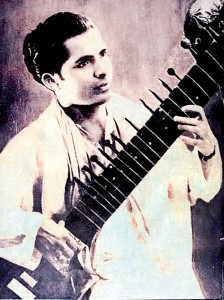

His first musical encounters came from singing in church choirs. He also learnt to play the guitar and harmonium. After leaving school, he trained as a teacher and began his teaching career at the Mt. Calvary School in Galle. In 1939, he resigned from his teaching post to study vocal music at Shanthiniketan, the art school founded by Rabindranath Tagore. From 1940 to 1944 he studied North Indian classical raga music at the Bhatkande College of Music in Lucknow, achieving top marks in both sitar and vocal performance.

When Sunil returned to Sri Lanka in late 1944, he embarked on a new direction for his music. From scratch, he created a new song idiom that a local person could identify as belonging to this country. He achieved this by moving away from Hindustani classical raga music, which attracted a small and narrow audience in Sri Lanka, to create a popular Sinhala song idiom that was understandable to most Sri Lankans, particularly the Sinhalese. In the transitional years from colonialism to independence, his songs contributed to uplift the nationalist fervour of an ever-growing audience scattered throughout the Sinhala-speaking countryside.

Sunil began his recording career at Radio Ceylon in 1946 when he recorded ‘Olu Pipila’. No song had ever sounded like it. The song unleashed a new vigour and direction for Sinhala music and remains a pivotal moment in the history of twentieth-century music in this country.

Over the next six years, Sunil composed and recorded over 100 songs for Radio Ceylon. He formed his own ten-piece orchestra consisting of musicians such as Pandit W. D. Amaradeva, Percy Wijewardane, Joe Costa, Mrs. Costa, Sarathsena, and Rajah Dahanayake. His orchestra included violins, bamboo flutes, guitar, Hawaiian guitar, cello and Oriental percussion instruments, carefully selected and orchestrated to achieve the right weight and balance for his voice.

Success came very early. His songs were popular on radio, published in songbooks, and were picked up and sung at family get-togethers, school outings, parties, picnics, and by military bands.

Though largely about village life and pastoral scenes there was also a vast diversity in the themes of his songs.

For instance, in ‘Mage himiyaneni (Siri sangabo)’, which Sunil recorded in 1948 or 1949, the theme of the song is based on an account in the Mahavansa in which the wife of King Siri Sangabo asks the king to return to her after he had abdicated his throne to go off and live a life of solitude and meditation.

What defines his music as Sinhala? It was partly the way he uses the Sinhala language. He often applied the Sinhala laghu-guru bedha in his compositions. This is the system of short and long syllables in the Sinhala language which governs the rhythms and metres of the lyrics. Equally fundamental were the gestures of his music, which were unmistakably Sinhala. In many respects the gestures in his music were more important than the choice of musical instruments, the harmonic or tonal language of his music, or the rules governing the rhythms and melodies of his songs.

A pioneer: Sunil Santha moved away from Hindustani classical raga music to create a popular Sinhala song idiom

But soon, a few intellectuals and musicians, who believed Indian classical raga music offered the only source for new music in Sri Lanka, felt threatened by Sunil’s success and popularity and wielded their influence to oppose or undermine his quest for indigenous music. It began with a series of ill-conceived policies implemented by the music section at Radio Ceylon in the 1950s. On the surface, the policies were supposed to improve the standard of Radio Ceylon recording artists, but they resulted in certain musical instruments being banned on any Sinhala song recorded at Radio Ceylon, including the piano and harmonium; while elements of counterpoint and harmony intrinsic to song orchestrations were forbidden. Recording artists were also required to attend an audition or risk being sacked. In truth, the policies introduced into Radio Ceylon in the 1950s were simply a tool for regulating music and to rein in recording artists and composers involved in the making and shaping of indigenous music, especially Sunil Santha.

Sunil’s services as a Radio Ceylon recording artist were terminated in 1952 after he refused to audition on the grounds that Hindustani music standards were being imposed on Sinhala recording artists. With the benefit of hindsight and sixty years reflection, it is astonishing that one of this country’s most successful recording artists, as Sunil had become by 1947, was required to audition for Radio Ceylon in 1952.

From 1952 to 1967, Sunil was largely absent from the Sri Lankan music world. During these years, he spent his time with his family, cooking meals, or doing chores and odd jobs around the home. But opportunities did arise for Sunil to step back into the limelight. For instance, in 1956, film director Dr. Lester James Peries, who had a special affection for Sunil, invited him to compose the music for his first film ‘Rekawa’. Sunil agreed and he composed the music for the lyrics, which were written by Fr. Marcelline Jayakody. These film songs, with their charming and distinctive Sinhala characteristics, are still popular today as is Lester’s film itself. Sunil also composed the music to Lester’s second film ‘Sandeshaya’ which was released in 1960.

Sunil also re-emerged on Radio Ceylon to record the occasional song such as the elegy song he composed to honour Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike after his assassination in late September 1959.

In 1967, mainly due to changes within the UNP government of Dudley Senanayake, which resulted in a new Minister of Broadcasting and the appointment of Neville Jayaweera as the new Chairman and Director-General of Radio Ceylon, the doors of Radio Ceylon were once again opened to Sunil Santha and he was back recording his songs. With his return to Radio Ceylon, came a new energy and direction to his music. He began to experiment in his compositions to refine the melodic contours of his songs to one, two, three or five notes. For instance, in ‘Gum Gum Gum’ a song about the movement of bumble bees – and one of his best experimental songs – Sunil composed the entire melody of the song on one note, but the tune is so well-composed that listeners are not aware of it. The song sounds melodious and it is a testimony to his great ingenuity and craftsmanship as a composer.

There was another side to his new found creative energy, which was to give opportunities to a new generation of singers and recording artist to be involved in his music. He surrounded himself with some of the brightest and talented recording artists of this country, most notably, Ivor Dennis, Narada Dissasekara, Rohitha Wijesooriya, Victor Rathnayake, Visharada Nalini Ranasinghe and Amitha Dalugama, who were almost always present at the recording sessions and featured on the songs Sunil Santha recorded at Radio Ceylon from 1967. Some of these songs Sunil recorded with these artists were ‘Manu lowa mal gonne’, ‘Thel gala’, ‘Walakulin besa’, ‘Muhudey ho weraley ho’, ‘Sarada wala geba’, ‘Maley maley maley’, ‘Reyey sonduru rayey’ and ‘Emba ganga’.

The public knew Sunil as a “composer and recording artist”, but Sunil had other identities too. He was also a husband and father and this side of his personality, known to his family and closest friends, revealed him to be an uncomplicated man with a resolute strength of character to pass any test life threw at him.

Speaking about his father recently, his son Lanka Santha said, “I have never seen such an intelligent person. I never heard my father sing or play a musical instrument at home. All of his song compositions were conceived in his mind. He would scribble down ideas for his songs and then go to the recording studio and record them.”

“He was a great father. He took care of the four of us and showed us the correct path for success. My mother was with him always and helped him in many ways.”

“His morals were untouchable, especially since he was in the music and movie industries. This is so unbelievable because everyone who has seen him in those days [1950s] agrees that he was the most handsome guy in Sri Lanka. He never took a female in his care alone. Wherever he went, people respected him, and still do today.”

The last six weeks of Sunil Santha’s life were the most difficult and painful. It began in the early evening of Saturday, February 28, 1981 when his third son Jagath Santha, aged 23, drowned in the swimming pool of the Blue Ocean Hotel in Negombo while he was attending the Sri Lanka Steel Corporation’s Engineers Union AGM.

Sunil Santha was devastated. He shut himself in his room for long periods and surrounded himself with photos of his son. Not long after Sunil was helping his eldest son Sunil Santha (Junior) to erect a TV antenna when he complained of feeling unwell. On Saturday April 11, 1981, just three days short of his 66th birthday, he died after suffering a heart attack.

His death was a bolt out of the blue. Lanka Santha says, “My father was extremely healthy and our family never expected him to get sick in this way.”

One hundred years after his birth, Sunil Santha is a national treasure. His songs live on seventy years after they were first broadcast on Radio Ceylon. There are few composers and recording artists who can claim to hold such a huge and enduring legacy. For this reason he ranks, rightly so, with the best of the world’s great composers of popular songs.