Tiger, Tiger burning bright, not the two-legged kind but the eight-legged

They would scout the area during the day, looking for spots where these elusive creatures would be hiding and traverse the same path at night.

It was on one such night-foray, when the moon was in a game of hide-and-seek, that the research team headed by environmentalist Ranil  Nanayakkara of Biodiversity Education and Research (BEAR), with a dry wind whipping their faces on Mannar island, stumbled across these fast-scuttling creatures.

Nanayakkara of Biodiversity Education and Research (BEAR), with a dry wind whipping their faces on Mannar island, stumbled across these fast-scuttling creatures.

The find centred on special ‘Tigers’ of a different kind – not the two-legged variety who had been roaming the area at will before 2009, but the eight-legged kind not thought to be in Sri Lanka after Adam’s (Rama’s) Bridge vanished, severing the close attachment of the country with the Indian subcontinent.

Ranil and his team could not believe their eyes. Having emerged from the innermost recesses of a deep hollow of a tree, spotlighted by their torches was the large, colourful tarantula, Rameshwaram ornamental or Poecilotheria hanumavilasumica.

“This was a unique discovery,” says Ranil, pointing out that it was the first time that the critically-endangered species of Theraphosidae, Poecilotheria hanumavilasumica was discovered outside of its native habitat in India, expanding its range to northern Sri Lanka.

Explaining that arboreal spiders in the genus Poecilotheria are represented by 16 species and restricted to India and Sri Lanka, he says that each country has eight endemic species.

Ranil flips back the pages of time to underscore that this find in Mannar indicates that during the land-bridge (Rama’s or Adam’s Bridge) connection between India and Sri Lanka in the Pleistocene epoch, biotic exchange took place between the two countries dispersing taxa through the land connections.

The find was in 2012, when Ranil along with co-founder of BEAR, Nilantha Vishvanath, and field assistant T.G. Tharaka Kusuminda under the guidance and supervision of Dr. G.A.S.M. Ganehiarachchi of the University of Kelaniya was conducting an island-wide search for the

Threat display by Poecilotheria fasciata

Poecilotheria genus. With the permit being obtained from the Department of Wildlife Conservation, it was the Biodiversity Secretariat of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy which supported the team to carry out the study.

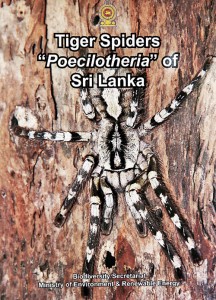

With the completion of the search, not only has the team’s findings about Poecilotheria hanumavilasumica been highlighted in the Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity in February to much commendation but also much more in the form of a book — Tiger Spiders “Poecilotheria” of Sri Lanka – been published.

While each and every detail about spiders has been incorporated in this book, the second from author Ranil on these creatures, he also makes use of the opportunity to press home the importance of nature conservation to ensure that “the environment we leave behind remains at least as good as the one we inherited”.

Urging the need to become active in “this cause” of nature conservation, Ranil warns that otherwise “tomorrow may be too late”.

Handy the book on ‘Tiger Spiders’ published by the Biodiversity Secretariat of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy may be, but into its pages are tightly-packed information about one of the oldest and most diverse groups of terrestrial organisms, with detailed sketches and numerous images.

Interestingly, the images are not limited to spiders alone but include different landscapes of this country to prove that Sri Lanka is truly a “biodiversity hotspot” in both fauna and flora. There is also a walk back in time to describe how Sri Lanka was once a part of the supercontinent Gondwana which included South America, Africa, India and Antarctica.

The precision with which scientific classifications of spiders are dealt with, meanwhile, makes it easy even for the uninitiated to grasp the basic details about this class of Arachnida.

Little nuggets leap out: Spiders are distributed all over the world on every continent except Antarctica and occupy nearly all of the habitats found on earth with the exception of the air and the sea; their size ranges from a pin-head (a mere 0.36mm) to a body length of 90mm; only a few species are herbivorous while all others are predatory and feed on prey ranging from small insects to small mammals and birds.

While spiders fall into the three sub-orders of Mesothelae, Mygalomorphae and Araneomorphae, the middle sub-order comprises tarantulas. “Despite their (tarantulas) large size, they are less dangerous than is commonly perceived. A bite can be deadly for insects and vertebrates, up to the size of a dog, but for a human victim, it is usually no worse than a wasp-sting. Nevertheless, human fatalities have occurred and allergic reactions are a danger,” says Ranil.

The description of ‘spider silk’ and the different types of webs would keep the reader entangled well in the book, with the courtship details of pedipal-tapping on the web and leg-waving would certainly draw a smile. Stressing the possibility of using spiders as ‘bio-control agents’ in controlling pests, the book also brings to light the use of spider silk in the production of bullet-proof vests, telescopic sights and fabric.

Referring to tarantulas in indigenous medicine, it states that spider silk is applied to wounds to stop bleeding, mixed with olive oil to alleviate ear-ache and in combination with jaggery, ingested to control certain recurring fevers, with the same concoction used as a styptic and healing agent and also as an anti-pyretic agent by application to the forehead.

The spider venom or the spider as a whole, meanwhile, is used to treat angina and heart disorders, cystitis, diabetes, mood swings, multiple sclerosis, restless limbs and chorea, as a pain-killer etc.

Dealing with the mythology and folklore surrounding this much-maligned creature, Ranil explains the perception of villagers that when a tarantula bites, the victim curls up and draws in his arms and legs in a manner of a spider trying to hide. This observation is not without foundation as such physical contractions may occur due to muscle spasms and pain that the victim may be experiencing after the bite.

Among the other tidbits of information which makes it difficult for the reader to put down this book are the prey-catching tactics. Unlike other types of spiders which use a web for this task essential for survival, Poecilotheria bides their time, awaiting unsuspecting insects, larvae, beetles and even small birds and small mammals such as bats.

It is a lightning ambush, thereafter, with the tarantulas lunging at the prey with exceptional speed and usingvenom to immobilize them. Once the prey have been secured, these opportunistic feeders wrap up these morsels in silk and take in their fill.

Much more fascinating details of these feared creatures are available at the flick of the pages in this book which is a must-own not only for spider lovers but those who wish to be lured towards liking them.