Sunday Times 2

The Last Gentleman

Before it even begins — the bouncy bus journey from the Pettah to the Galle Road and down the coastline — the B’s are buzzing, like stingless honeybees. Beruwela is our destination, a seaside town beyond the holiday resort of Bentota. Thinking about the journey’s object has set in motion a bevy of B words and names that will only beget more B’s as the story unwinds.

We are on our way to see Bevis Bawa — the legendary laird of Brief, Beruwela. It is a bright morning in December 1989.

“BRIEF”, as in a barrister’s brief, was the name given to a property that Bevis Bawa received from his advocate father E. W. Bawa. Brief is the house and garden Bevis Bawa built and occupied for much of his life.

But first a bit of background.

That this much postponed visit is finally happening is prompted by the fear that further delay could mean a lost opportunity. Bevis Bawa, who is a living part of Ceylon social history, is old, frail and blind. We are on a brief vacation from overseas, and we don’t want to wait another day.

From as far back as we remember, when we were very, very young, we heard tell of the real and mythical Mr. Bawa. He and others have generated a compendium of Bawa tales — most of them amusing, and many tall, befitting the tallest man in Ceylon.

Our favourite was one we read in a newspaper. A young Bevis Bawa had to appear in court in a minor traffic rules infringement case. When he stood up to answer questions, the judge looked hard and ordered him to “get off that box.” Puzzled, Bawa said, “What box, your Honour?” “The box you are standing on. Stop arguing and get off that box.” “But, your Honour, there is no box.” A lawyer swiftly moved in to explain to the judge that Mr. Bawa was an exceptionally tall witness who had no need for height-enhancing props.

Being unusually tall helped Mr. Bawa get his driving licence when he was 14, and join the volunteer Ceylon Light Infantry as the youngest local officer ever. So the stories go.

As the officer with the longest stride in the Army, he would leave his troops far behind when marching on the parade ground. His high visibility during his years as aide-de-camp to four successive Governors meant that all eyes were on Bevis and not on the Governors, their wives, or their fancy, fussy entourage.

Bevis Bawa was born to stand out, as a person and a personality. At a time when the average height of a Ceylon male was 5 feet 5 ½ inches and that of a British male 5 feet 7 ¾ inches, Bevis Bawa was 6 feet 7 inches, and close to eight feet “in boots and plumed helmet.”

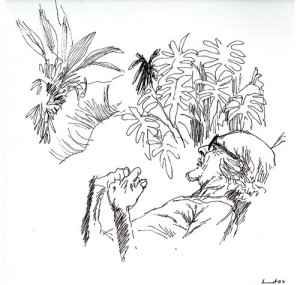

The last chapter. Bevis Bawa by George Beven

The Bawa name is a noun in the Sri Lanka Army, and it is only a matter of time before it is absorbed into the general vocabulary. Officers and soldiers, speaking in English and Sinhala, use “baawa” to denote the superlative degree; a “baawa” is something “exceptional, without peer, statistically significant.”

Gregarious, engaging, and charming, Bevis Bawa has friends everywhere. He loves company. His range of acquaintance includes European royalty, internationally famed artists and writers, and legions in his homeland, from prime ministers to postmen.

Acknowledging that Mr. Bawa is one of our most famous and beloved citizens, we have to admit that we have no clear idea of what Mr. Bawa’s fame is built on exactly. Blurry is his claim to a permanent niche in history, but the niche has already been made for him.

From all we’ve heard, we know Mr. Bawa to be an aristocrat in the Ceylonese meaning of the word, and a gentleman in the best, old-fashioned sense. The photographer Dominic Sansoni, a family friend, describes him as “the last gentleman.”

Bevis Bawa is the sum of his parts. He is a gifted artist and an instinctual landscaper. As a writer he has contributed stories and drawings to newspapers. His touch is light and expressive. His garden in Beruwela is called a piece of the original Eden. Creating beautiful gardens for affluent clients is the only wage-earning job he has had, after leaving the Army and retiring from colonial service. Whatever he puts his hand to — be it a drawing, a story, a friendship, a party, a piece of landscape — it is transformed by his benign creativity into something quite special.

B is for Beauty. The creation of beautiful things and the appreciation and understanding of the beautiful come naturally to Mr. Bawa. He is an artist to the fingertips.

Bevis Bawa

B is for Bonhomme and Bonhomie. Bevis Bawa is the most good-natured of beings, radiating geniality. No one who meets him comes away with anything but positive thoughts, a happy state of mind.

Bon viveur well describes Mr. Bawa, a man who loves life and the good things it offers.

The Bawa name has almost disappeared. The Bawas were a respected and affluent Muslim family living on the southwest coast. The name was first associated with gems and jewellery, then the law, and finally with artistically rendered gardens and homes, all famous, here and abroad.

Bevis Bawa (1909-1992) was the son of the distinguished lawyer B. W. Bawa. His family was Muslim, English, Scottish and Ceylon Burgher.

Bevis’s mother’s best friend was Dr. Claribel (née van Dort) Spittel, wife of Dr. R. L. Spittel, the surgeon and writer. According to Christine Spittel-Wilson and Anne Andersen, Dr. Spittel’s daughter and granddaughter, the two families were very close. According to cousin Christine, it was R. L. Spittel who brought the baby Bevis into the world, on April 26, 1909, at the Spittel nursing home and residence Wycherley. And it was Dr. Spittel who fixed the baby Bevis’s harelip, a surgical stitching so good few noticed it when Bevis grew up, although he was said to have been keenly self-conscious about it.

The Bawas were regular visitors at Wycherley, as friends and occasional patients, when medical needs arose. Christine Spittel and Bevis Bawa were about the same age, and as children they practically “grew up together.” They were so much in each other’s company that Mrs. Bawa and Dr. Mrs. Spittel considered a future marriage possibility between their son and daughter, a pairing that became highly unlikely when Bevis started soaring to incredible height, and Christine came to recognise very early that Bevis was not of the “marrying kind.” That family episode was narrated by Christine with a light laugh and a twinkle in her eye.

We arrive at Beruwela. Our party of three includes Younger Brother and a school acquaintance. We carry an introduction from a mutual friend,

Brief. Photo: Dominic Sansoni (courtesy of Three Blind Men)

the lawyer Mr. Archibald Drieberg. Mr. Drieberg told us that the last time he visited Brief, Bevis moaned that he had no money left to entertain guests, and that callers could pick limes in the garden and make themselves a jug of juice.

The taxi ride from the bus halt takes us through a long leafy road that twists, turns, dips and rises to finally arrive at the Bawa property. Without knowing it, we were inside the Bawa estate long before we arrived at the house.

Domestic staff receive us at a black-and-white painted front door. We are led down a long polished corridor and into a sun-reflecting veranda-patio. Stretched out on a jardin chaise longue is a thin long figure, dressed in a pale striped sarong and a white vest with short sleeves. Mr. Bawa, bachelor elder, lifts his silvery head to greet us. Stretched out behind him, soaking up the sunshine, is the famous garden.

“And how is dear Archie?” our host asks, and the visit begins.

We are on common ground as young and senior Old Boys of Royal College, Colombo. Archie Drieberg and Bevis Bawa were classmates in the Twenties, along with Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, Mr. J. R. Jayewardene, and the musician Elmer de Haan.

Three strangers sitting round a famous but sightless person can be an awkward social situation. We have a list of conversation cues, and soon we are chatting and chuckling like old acquaintances. When we explain that we are on a short Christmas vacation, the topic turns to travel and the Far East.

“I have a wonderful memory of Hong Kong,” says Mr. Bawa. “I was a young man on a P&O cruise. Your grand-uncle Noel Spittel, brother of R. L., was one of the passengers. I bought a watch in Kowloon and got back on the ship just in time before it pulled out of Hong Kong harbour. Behind us was a boat speeding to catch up with us. In it was the watch dealer, bringing me the balance money I had forgotten to take. I will never forget that amazing display of honesty.”

We told Mr. Bawa that the everyday honesty was one of the first things that struck us on moving to Hong Kong.

The garden Brief seen from the house. Pic: tripadvisor, tripwolf.com

“And the Chinese are very attractive people too, don’t you think?” We did think so

Mr. Bawa’s clear eye for beauty did not blind him to the less-than-beautiful.

During the ’70s, there was an exhibition of Bevis Bawa art, mostly caricatures, in crayon and water colours, at the Alliance Francaise. The faces, visages stretched to extremes of ugliness, were mostly recognisable politicians. It was a gallery of grotesques. The only fair and attractive face on display was that of fellow artist Barbara Sansoni. She was the only woman among a hundred outrageously unappealing male faces.

Bevis Bawa’s art draws a direct line to the wondrously versatile 19th-century Ceylon artist J. L. K. van Dort, who had a great gift for caricature. Bawa said he used to collect van Dorts. On a wall in another part of the house is a pen-and-ink van Dort jungle scene, the black sketch lines bleached to a dark purple-brown by the years or the sunlight pouring into the room.

On a side table next to Mr. Bawa is an audio-tape of Ken Follett’s spy thriller, “Eye of the Needle.”

“I have told my friends that if they want to bring me a gift, bring me a book to listen to. When you are blind and alone, you have only your memories. After a while you get tired of your own thoughts.”

From a distance, crowded sounds from the far end of the property press through the trees and the shrubbery. Like a clamour of big boisterous birds. Boys’ voices.

“That’s S. Thomas’ Preparatory School,” Mr. Bawa says with an avuncular smile. “We have many schools visiting. They come here for a picnic outing. It’s nice to have company.”

A word about the garden would be in order. How does Mr. Bawa go about making a garden, for himself and for others. Does he have a list of favourite trees? “I don’t know the names of any trees,” he says. “If I see a tree I like, I put it in.”

Just then a young gardener appears. He is bare-chested and wearing a tucked-up sarong. He is pushing a wheelbarrow on a path edging the lawn. He stops to wipe his brow. A yellow flower breaks loose from a branch above and drifts down, drawing an invisible wavy line past the slender half-naked man before it touches the grass. It is an artistic moment. You get the sense that life at Brief must be one endless succession of such graceful, eloquent moments.

The moment happened in silence. The voices at the bottom of the garden have suddenly stopped.

“They’re having lunch,” chuckled Mr. Bawa. “Eating is serious business for boys. For everyone.”

It’s noon. A member of staff has discreetly appeared at our side.

“My helpers are very polite,” says Mr. Bawa. “This is how they tell guests it is my lunch hour. But they don’t want you to go.”

Domestic staff have Mr. Bawa’s affection and esteem. He despises the word “servant”; his attendees are his “helpers,” he insists.

We stand up to take a walk, promising to be back. First, a stroll through the house, with the owner’s permission.

We go past a table set for one. Lunch is a bowl of thin vegetable broth, string-hoppers, and pale scrambled egg sprinkled with fennel leaf.

The house itself is unremarkable. It’s the contents, the art and the furniture, that invite attention.

Mr. Bawa must love books. One room is covered wall to wall with them. Classics. Novels. Poetry. Biography. History. Art. The Iliad. The Divine Comedy. Cavafy. Paul Bowles. Jean Genet. Gore Vidal. Tennessee William’s Memoirs. Two shelves of faded hardbacks of the now forgotten British writer Beverley Nichols.

The rooms and corridors are adorned with sculptures and framed art. One semi-outdoors wall is taken up by Australian artist Donald Friend’s surreal mural of a Ceylon fantasia. Damp threatens to undo the fresco.

A black-and-white photograph at the far end of the house glows with cinematic luminosity. Lying on the grass of Brief are actors Peter Finch and Vivian Leigh, among others. The image dates from 1953, when the Hollywood film “Elephant Walk” was being shot in Ceylon. The talk was that Vivian Leigh’s nervous breakdown was caused largely by being smitten with an indifferent Bevis Bawa, and that was why she had to be replaced by Elizabeth Taylor. The gossamer of harmless, sequinned gossip drapes most Bawa stories.

Into the garden.

The actual land on which Brief stands is relatively small, but gives the impression of a larger spread through clever landscaping. You finish one circuit, and want to do more in order to feel exercised.

We have been alerted to “naughty” sculpture hiding in the greenery. Most of the statues are by a much younger Mr. Bawa, and you can picture him working on them with a mischievous schoolboy smile.

Pan plays a flute under a plumeria tree. A satyr shows a hoof from under a croton bush. An elfin face on a leaf-clad wall sports a long penile-pensile pun of a nose.

Art peeps and winks between the leaves. This is Bawa country, where nature and artifice hold hands, hug, kiss, intertwine.

When we get back to the patio, Mr. Bawa has had his lunch and is back in his long chair. The man once so famous for his startling vertical profile is now in horizontal recline.

We have brought along a book, a selection of Bevis Bawa’s Fifties newspaper articles, to be autographed. A helper steps forward and gives Mr. Bawa a black felt-tip pen. Mr. Bawa writes ‘Bevis’. The helper dots the ‘i’ and draws a line under the name. Master and helper are in perfect wordless accord.

We don’t wish to take up any more of our host’s time. Drowsiness hangs in the afternoon air. We promise to come back.

“You must,” Mr. Bawa says, a little sadly. “You sound such nice people. Why did you wait till I became blind before paying me a visit?”

We repeat we will be back.

We never did make that return visit.

There is a story accompanying this story. We had introduced ourselves to Mr. Bawa as being in the publishing business, and during the conversation offered to pen a feature about the visit. The plan was to write a story for a magazine. Nothing came of it. The Beruwela visit slid to the back of our mind on our return to frenetically busy Hong Kong. A year later a third party let us know that Mr. Bawa was disappointed that the promised article had failed to appear. We felt remorse. We told our guilty self that the story would be written — some day. Mr. Bawa passed away in September 1992. He was cremated in his garden, and his ashes buried under a tree just behind where we remember him relaxing on his veranda.

Today, 26 years after that visit, we sign this 2,600-word card dedicated to the memory of the legend of Beruwela. The last gentleman.

Apologies for the late story, Mr. Bawa. Happy Birthday.