Columns

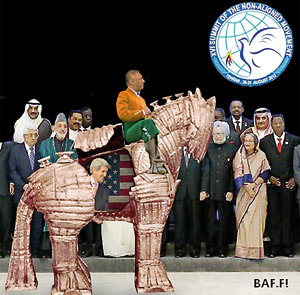

Is Mangala getting ‘Aligned’ at the expense of the ‘Non-Aligned?’

View(s): With the flying visit to Colombo by US Secretary of State John Kerry, Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera’s priorities in foreign policy become increasingly clear. He declared in a recent interview that his ambition is “somehow to get US president Barack Obama to visit Sri Lanka at one point or another.”

With the flying visit to Colombo by US Secretary of State John Kerry, Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera’s priorities in foreign policy become increasingly clear. He declared in a recent interview that his ambition is “somehow to get US president Barack Obama to visit Sri Lanka at one point or another.”

This is while President Maithripala Sirisena has consistently maintained that his government’s foreign policy is ‘Non-Aligned.’ The president repeatedly made this assertion during his foreign trips. It was reiterated most recently in his address to the nation on reaching the deadline of the 100-Days program.

Samaraweera maintains that his intention is to ‘move Sri Lanka’s foreign relations back to the centre.’ But the signals sent out in the international arena tell a different story. One example was the recent 60th anniversary commemoration of the Bandung Conference. Sri Lanka was not even represented by its Foreign Minister at the meeting of world leaders in Indonesia last month. Ceylon (Sri Lanka) along with India, Pakistan, Burma (Myanmar) and Indonesia, was one of the organizers of the historic 1955 Asian-African Conference – the forerunner of the Non-Aligned Movement.

Samaraweera maintains that his intention is to ‘move Sri Lanka’s foreign relations back to the centre.’ But the signals sent out in the international arena tell a different story. One example was the recent 60th anniversary commemoration of the Bandung Conference. Sri Lanka was not even represented by its Foreign Minister at the meeting of world leaders in Indonesia last month. Ceylon (Sri Lanka) along with India, Pakistan, Burma (Myanmar) and Indonesia, was one of the organizers of the historic 1955 Asian-African Conference – the forerunner of the Non-Aligned Movement.

Is there a devaluation of Non-Alignment taking place in Sri Lanka’s foreign relations? And is Samaraweera kicking into his own goal by undermining Sri Lanka’s status within the NAM?

On Monday, the 16th session of the UN Working Group on the Right to Development scheduled to start in Geneva had to be deferred because of the non-appointment of a chairperson-rapporteur. The chair for the last three years was Tamara Kunanayakam, former Sri Lanka ambassador to the UN. Kunanayakam’s re-appointment as chair of the Working Group was reportedly opposed by one country – Sri Lanka. This move came as a shock not only to Kunanayakam but to all the member countries who, by all accounts, had been highly appreciative of her work as chair. There was no response from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the Sri Lanka Mission in Geneva, to queries on Sri Lanka’s opposition to the appointment. Below are excerpts from an email interview with Kunanayakam on the disruption of the 16th session of the Working Group and its implications:

- 1. Briefly – what does ‘Right to Development’ mean for developing countries like Sri Lanka? What tangible benefits would accrue?

The right to development is a human right like any other human right. The ultimate goal of our work at the United Nations is to make it a reality for all people around the world, especially in the developing countries, which, because of their unequal position in the international order, are more vulnerable to external decision-making. The right to development places the human person and all peoples at the centre of development, as its subject, as its driving force, as its architect, not as its object.

It is unique in that it brings together human rights and the duty of States to cooperate with each other, on the basis of sovereign equality, to create the conditions for their realisation – both at the national level and at the international level. It is the duty of States to eliminate national and international obstacles that stand in the way of realising the right to development.

The principal architects of the Declaration on the Right to Development, which was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1986, were the newly independent States, expressing themselves through the Non-Aligned Movement.

However, as you know, because of the unjust international order and inequalities in the distribution of wealth and power, developing countries continue to face numerous obstacles. They do not have equal access to markets, technology, capital, and other resources. They do not have equal access to decision-making in the international trade and financial institutions. And their dependence on external markets and foreign debt, have made them even more vulnerable to political domination and external intervention, including IMF/World Bank conditionalities, sanctions, embargoes, threats, etc.

Globalization, which has served the needs of transnational corporations rather than those of ordinary people, has accentuated disparities. According to a Report of Credit Suisse, almost half the global wealth in 2013 was owned by the richest 1%; today we would have reached the half mark. A January 2015 ILO report revealed that more than 61 million jobs have been lost since the start of the global crisis in 2008, and an extra 10 million people worldwide are likely to be unemployed in the next four years.

You can imagine what the realisation of the right to development will mean to the 80% of humanity who live on less than US$ 10 a day, which is 95% of developing country population, according to a World Bank report.

I hear that the 16th session of the UN Working Group on the Right to Development that was scheduled to start in Geneva on Mon 27th April had to be unexpectedly deferred, owing to the non-appointment of a chairperson-rapporteur. I understand it was the expectation of the members of the Group that you, as the chair-rapporteur for the past 3-4 years, would be re-appointed, but this did not happen. This was reportedly because the Sri Lanka Foreign Ministry had opposed your candidacy. Can you confirm this?

It is, indeed, very unfortunate that the UN Intergovernmental Working Group on the Right to Development was forced to defer its 16th session, indefinitely. On the eve of its meeting, the Non-Aligned Movement was faced with an unprecedented crisis, with one of its members objecting to my nomination. We were given to understand that the objection came from Sri Lanka.

Why was the 16th session important?

At this session, the Group was to consider an important document that I was asked by the Human Rights Council to prepare, with proposals for improving its effectiveness and efficiency. Due to opposition from some of the Western countries, particularly the United States, which was the only country voting against the Declaration, the international community has not been able to implement this human right. The decision to defer the 16th session means that we are losing two whole years during which the Working Group will be unable to act or contribute. And these two years are vital years, because the UN will be deciding on its actions for the next decade on issues that will determine the future of humanity – the Post-2015 Development Agenda, the Framework Convention on Climate Change, and Third International Conference on Financing for Development.

The developing countries had hoped to use my document to make an important step forward by next year when the UN will be commemorating the 30th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration on the Right to Development.

What official communication (if any) did you and other member of the Working Group receive of this development, and who conveyed it? Was the Sri Lanka Mission in Geneva associated with the move?

It appeared that the Sri Lanka Mission in Geneva had informed the Coordinator of the Non-Aligned Movement of the decision on the eve of the 16th session. The established practice is for NAM to nominate the Chairperson-Rapporteur. The information was communicated to me by the Coordinator on Thursday evening, at 21h. I had just arrived in Geneva. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, which is the secretariat of the Working Group, heard about it only on Friday evening. Several other States members said they had not been aware that there was a problem until the agenda item on election of the Chairperson-Rapporteur was taken up on the Monday morning.

- 2. What reason was given for your non-appointment? Were there other prospective candidates competing for the position?

No reasons were given. In fact, a number of developing country delegations asked me the same question.

I was chosen for my expertise on the right to development, a subject that I had worked on for more than 25 years, in fact, for most of my professional career. They knew that I was committed to the issue. The position of Chairperson-Rapporteur was honorary and there were no political, financial or career advantages that went along with it. My being Chair was not only beneficial to the work of the Working Group. Moreover, despite my being an independent expert, it also benefited the image of the country of my nationality.

The fact that NAM proposed its Coordinator as an interim Chair that morning seems to indicate that the NAM member States had not been given sufficient notice to find an alternative.

- 3. How did other member states / groups of states react to this development?

It was very apparent that almost all were taken by surprise and that the developing countries saw it as a severe setback for the realization of the right to development, for the advancement of their interests, and for the unity of the Non-Aligned Movement. There was a lot of concern among them that the Working Group would be effectively blocked for two years, that it would not be in a position to contribute toward crucial work being carried out by the United Nations in the areas of development, climate change and financing for development. They had hoped that my report containing proposals to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the Working Group would provide the impetus to move it forward after 15 years of efforts to overcome political obstacles.

Leave a Reply

Post Comment