Love Cake for Mr. Shakespeare

ANOTHER year and another missed big occasion. A VVIP Birthday Combine. This makes it three years in a row. But this time we won’t let it pass. So, without much ado, let’s do the belated honours (we are only 17 days late, which is nothing in eternity). Two-and-a half weeks ago the calendar blazed a dies mirabilis. Magna natalis. April 23 is a miraculously special day, the birthday of many remarkable people.

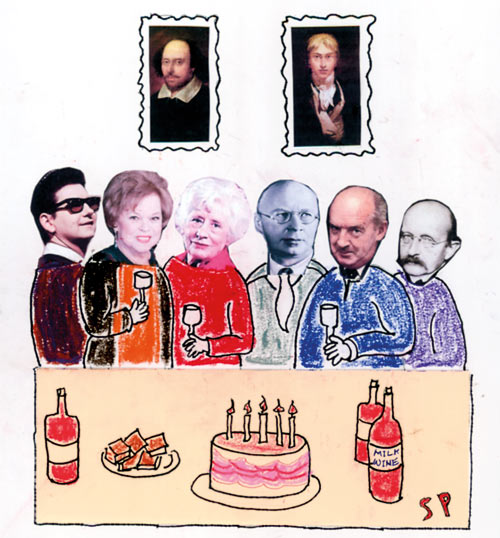

Starting with William Shakespeare, born 23 April 1564, let us go down the centuries to wish, in turn, J.M.W. Turner, English artist, born 23 April 1775; Sergei Prokofiev, Soviet-Russian composer, 23 April 1891, and Vladimir Nabokov, Russian-American writer, 23 April 1899.

Also, Max Planck, German physicist, 23 April 1858; Ngaio Marsh, detective story writer, 23 April 1895; Shirley Temple, American child actress and later US Ambassador, 23 April 1928; Roy Orbison, American musician, 23 April 1936.

Six famous men, two famous women, chosen from the long list of April 23 birthday celebrities; ours is a small but distinguished gathering.

It’s important that everyone is comfortable, that all are introduced and seen talking to one another. The world’s awe and respect is what they have in common. That explosive fusion of fame should put sufficient fizz into the party.

In get-togethers for the departed, especially the very long departed, there’s a risk the guests may be shy and could, without warning, vaporize, fade out, slip back into the Fourth Dimension, like Oscar Wilde’s Canterville Ghost. The further back in time they belong to, the greater the chances of instant evaporation or their simply failing to materialize at all. Let us honour the least likely to turn up by hanging their portraits, while hoping they may drop by even for a short visit.

First, the Greatest of Them All.

Our initial awareness, at a crawling age, of William Shakespeare was tactile. On a low shelf of the radio and gramophone cabinet was an assortment of souvenirs brought by our parents from their wartime years in England. One was a brass ashtray, pleasantly cool to the touch and heavy for its size. Once the grime and impacted cigarette droppings had been scraped off and the brass polished, you saw, gilded and glowing, Shakespeare’s home in Stratford-on-Avon. The ashtray was flat with moulded raised features, so you could feel the home and garden – run your fingertips over the roof thatching, the chimney, the windows, the low fence and gate, and the shrubbery. In the family album is a sepia photograph of Mother aged 23 standing at Shakespeare’s front gate with a group of Ceylon ladies draped in sarees. A deep quiet fills the scene. It must have felt like a day in 1616.

One day years later Mother came home carrying The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. She carried it the way she did when bringing home anything very special, such as a dachsund puppy, holding the precious cargo close to her chest in one arm, her other arm carrying her Grancino violin or the day’s groceries.

The Shakespeare book, like the Bible, was heavy, solemn-looking, beautiful. We couldn’t keep our hands off it. It was a souvenir from the Old Girls of Holy Family Convent, Bambalapitiya, thanking Mother for contributing to a Festival of Music, Drama and Dance to mark the 1964 Shakespeare Quatercentenary. Our dippings into the book started small, with the Sonnets, The Rape of Lucrece, A Lover’s Complaint, The Phoenix and the Turtle, and the intoxicating Venus and Adonis. The last was the sexiest, steamiest thing we had read (up to then). We went through the poem slowly, furtively, repeatedly.

Shakespeare had come to stay. There he was, on the shelf, to hold and behold, while Father and Mother would stub out their cigarettes into the Stratford ashtray.

When it was our turn to stand in front of Shakespeare’s house, an era later, in 2007, nothing appeared to have changed, except that the sepia photograph had burst into colour, into bloom. We stepped into the garden, where a Pakistani gardener informed us that all the plants and flowers he was growing were those of Elizabethan times. No modern hybrids allowed. Inside the house, the guide waved to the sparse furniture, the hearth and the thatched roof above our heads. There were no ceilings in those days, he said, and animals nested in the thatch and stirred as night fell, As:

Light thickens, and the crow

Makes wing to th’ rooky wood –

Good things of day begin to droop and drowse

While night’s black agents to their prey do rouse.

In the souvenir shop, we picked up tiny editions of Macbeth and Twelfth Night, in brown and red leather covers, each small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. A long pencil capped with Shakespeare’s long-haired likeness in plastic, and a black rubber eraser printed in white letters with the Macbeth quote, “OUT, DAMNED SPOT,” completed our Stratford purchases. We saw no Stratford brass ashtrays.

We were back in the garden in time to see perch, on a wooden gate, a very plump Robin Redbreast.

The sun is God

Our next Great Guest, in chronological sequence, is Mr. Joseph Mallord William Turner. What we knew of Mr. Turner in our school years was what we saw and read of the great English artist in the school library. His sunsets, sunrises and seascapes appeared in the art books and encyclopedias. To anyone who idly played with watercolours, some of Mr. Turner’s effects may have seemed not that hard to achieve. When the hand goes lazy and the paintbrush trails water and colour across the paper, the resulting sweeps of washed blue, orange, red, green and grey suggest hazy Turner skies, misted Turner seas. Mr. Turner’s paintings, we learnt, were daring and revolutionary for their time, and anticipated things to come, such as Impressionism and Abstract art.

Many of us murmur Mr. Turner’s last words when we turn our faces to the sky: “The sun is God.”

The party is going well. The guests look substantial, almost mortal. No one has disappeared as yet. All seem at ease, and all are talking about the love cake and the milk wine.

Detective story writer Ngaio Marsh is in animated conversation with the Texan singer and song-writer Roy Orbison and Shirley Temple, the 1930s child actress who later became a US diplomat. Professor Planck stands near Russia-American writer Vladimir Nabokov and composer Sergei Prokoviev, who are chatting and guffawing richly in Russian. Both men are known for their flaying wit.

It is an intimidating gathering. You are nervous to even walk past the guests, still less walk up to them. The most we dare do is go around with a tray of canapés and eavesdrop on the gathered greatness.

The antipodes

We would like to tell the New Zealander Ms. Ngaio Marsh that we enjoy her books. They are satisfying reads, though not as ingeniously plotted as the murder stories of her crime fiction rival Agatha Christie. In their quasi-literary heft, Ms. Marsh’s books weigh more heavily against Mrs. Christie’s lighter weight but cleverer and no less sinister mysteries. Mrs. Marsh was also a theatre person; her books make references to the stage and stage life. It was from her we learnt that Macbeth is a bad-luck play to perform. The first Ngaio Marsh book we consumed was “A Surfeit of Lampreys.” The attraction was a voodoo doll skewered by a knitting needle on the cover. Black magic was another of our unhealthy childhood interests. Another attraction was the title. Lampreys sounded like Lamprais, the Portuguese-Dutch rice dish our great-aunts so deliciously made and cooked in plantain leaf. The book’s Lampreys refer to the main characters, a lovely New Zealand family living in London. They sing a carol that goes,

Two, two, lily-white boys,

Clothed all in green, O

One is one and all alone

And evermore shall be so.

The Shirley Temple chatting with Ms. Marsh is not the child actress but the politically active adult she grew up to be. Shirley Temple Black was a US diplomat who played a foreground-background role at a critical Cold War moment in US-Europe relations.

Looping the loop

The child actress was the curly-haired, doll-faced darling of ’30s Hollywood and the movie-going world. In 1936, Mother dressed up her sister Prudence, seven years younger, as a Shirley Temple lookalike and coached her to sing at a children’s song festival, held at the Regal Cinema, Colombo 1. Prudence was Shirley Temple’s age. Her song was “Animal Crackers”, from the 1935 film “Curly Top.” Mother would sing the clever lyrics to amuse us when we were of an age to be Curly Top’s male sidekick.

Animal crackers in my soup

Monkies and rabbits loop the loop,

Gosh, oh gee, but I have fun,

Swallowin’ animals one by one!

Walking down the street

The first time we heard or heard of RoyOrbison was when his “Pretty Woman” topped the charts and drove pop-rock fans wild in the Sixties. Older Brother brought home the single, and he and his rocker buddies Robin and Bertram Daniel, the late Everard Potger, and the late Kirone Vaidhyanathan would listen, shake heads, tap feet, and pluck invisible guitars to the irresistible “woman walking down the street.” The disc would spin again and again, and the pretty woman made to walk up and down and back and forth until she screamed that she had had enough. The song was, and is, one of the greatest ever. It has a drive, an originality, a deftness and a catchiness that defy analysis.

Pretty woman stop awhile

Pretty woman talk awhile

Pretty woman give your smile to me.

Two great Russians

We draw a blank with Professor Max Planck. We know nothing about Physics and Quantum Theory, except to spell the words, and so we glide past Mr. Planck.

The difference between Mr. Nabokov and Mr. Prokofiev was where their careers diverged. The writer left Russia as a child and made his home in America and Europe and condemned the Soviet regime ever after, while the composer stayed on in the Soviet Union and served as artist-ambassador on tours to Europe and America.

The first time we heard Mr. Prokofiev was in a BBC radio programme on 20th century music. The snatch of string music to catch our ear was a dark, scratchy patch of notes such as we had never heard before. Menacing, bow striking and bouncing off strings. The music faded out. We wanted it to go on. It would be years before we heard the complete Concerto in D major.

Mr. Prokofiev inched up closer one afternoon in 1969, when we were chatting over a garden fence in American suburbia, with a venerable gentleman whose name was Eldridge Pond. He was a Mid-Westerner, Chicago-born, and he had an uncle who had been a professor at the University of Chicago in the ’30s. As a schoolboy, Eldridge would be invited to lunch at his academic relative’s apartment on the campus, and there would be other faculty members and an occasional guest. One such guest was the composer and pianist Sergei Prokofiev. What did Mr. Prokofiev talk about that afternoon? Eldridge Pond had no idea. He was young and not especially interested in classical music.

That US year we would go into town and look for books and music bargains in Chicago stores. We had 16 US dollars a month pocket money. A marked-down record could be as affordable as one dollar. One of our purchases was an Igor Oistrakh recording of the Prokofiev Violin Concerto in D, a powerful, dazzlingly coloured, wrenchingly beautiful work.

Beauty and Pity

Vladimir Nabokov was a vague Slavic name until we picked up a handsome hefty plastic-covered hardback titled “Nabokov’s Congeries.” The book was in the collection of the American Library, at its old home in the old O. L. M. Macan Markar building, Galle Face. It was around 1967-68. On opening the book, the first words we saw was a description of homemade jams, glowing as if lit by neon inside their glass bottles. The jellies, sounding and looking so like the preserves made by two great-aunts who were great cooks, appeared in the short story “Signs and Symbols”. An elderly couple take the gift of conserves to their son, who is locked up in a mental asylum. The story ends tragically. As we would discover over time, reading more of Mr. Nabokov, that short story contained the Nabokov qualities of hyper-real reality conjured through the power of three-dimensionally vivid description, and the essential entwining of Beauty and Pity, essential characteristics the writer said were found in great literature.

That short story was the beginning of an infatuation with Mr. Nabokov. The peak Nabokov experience was reading the marvellous-notorious LOLITA, the book that made its author famous and rich. At 19 years, we were in ideal mental form to read LOLITA, which its author once described as an account of his “love affair with America.” Much of the plot unwinds during a long car ride across the United States. In the car are the two chief characters, the European professor Humbert Humbert and his 12-year-old lover.

LOLITA was one of the first books we picked up on returning from a year in the United States. It was 1970. The timing was perfect. As a guest of an American family, we too had gone on long car rides across American States and, like LOLITA’s illicit lovers, had stayed overnight in a succession of motels. The book magically retraced our own recent discovery of the US, and the treasures and trivia of Americana. We read LOLITA with the scents and sounds of America fresh in our nostrils and ears. Apart from its controversial plot, LOLITA was/is a glorious language treat – a grand Slavic-European-American buffet literary dinner prepared by one of literature’s master chefs. LOLITA has been described as a product of Nabokov’s love affair with the English Language.

The opening lines stay with the faithful, grateful reader long after he/she closes the book.

“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.”

It’s twilight outside, dark inside. We reach for a switch, hidden by a curtain, to turn on the chandelier lights. The room is ablaze. We turn around to find the room empty, the guests gone.

Quite, quite gone.