The miracle of the old-fashioned Mum

Mum turned 83 last month. I was not with her. Between us are an ocean and a continent. Yet the snip of the umbilical cord at birth cannot cut blood ties that bind. Distance does not disconnect hearts.

I haven’t seen her for over a year. She’s frail, I hear; too weak to walk in her precious garden. “I’m afraid I will tumble if I lean forward,” she says laughingly on the phone. Stubborn she is, and with an endearing sense of humour. The walker my brother gave her is gathering dust in a corner of the house. She won’t use it. She loves gardening. I picture her leaning forward to touch one of her beloved anthuriums and falling into them.

“Use the walker, mum,” I say.

“I don’t need it,” she says.

“You know mum. She just won’t!” my brother says.

She was 27 when I came into the world; the fourth of a brood of three and later six. Twenty-seven is a year short of my own girl. I too have lived some. As my nerves and body fray and decay from a lifetime of trying to balance a household of three, now two, and work, her life seems miraculous. She ran a huge house day upon day through the best years of her life. Five boys and a girl who would get up to every imaginable mischief, along with at least a dozen more cousins and relatives who strained our house at the seams. My childhood home, a sprawling bungalow and acre of garden, was a useful refuge for relatives. Grandmothers, cousins made it their home. Aunties and uncles would drop off their kids for months-long stays. We had a cook and a helper, and mum, to tackle chore upon endless household chore. The connotations of boredom that we now associate with that word were the fabric of her life since age 17. Without her, our family would have fallen apart. She was the calm centre of our whirlwind lives of school, home and mayhem.

I cut corners in my home, economising my contribution to home-making for money making and self growth. Making stringhoppers, patties, cutlets are avoidable hard labour to be outsourced if possible, if not eliminated altogether. But she did it. She did cutlets, patties, satay sticks, cakes, teatime porridges that I will never forget. I will never know how she did it; the prospect of running such a huge and extended family is too nightmarish. She put her own dreams – ambitions we will never know – on hold for us who have now drifted, physically far from her. I recall my little girl persona admiring her fingernails, bright red with a new coat of Cutex, as she stood in shimmering saree while dad fixed a corsage in her beehive hairdo for a night out. They went out, just the two of them, from time to time, leaving us to ransack her wardrobe for impromptu skits, and smear her makeup on our faces, leading to tearful showdowns on her return.

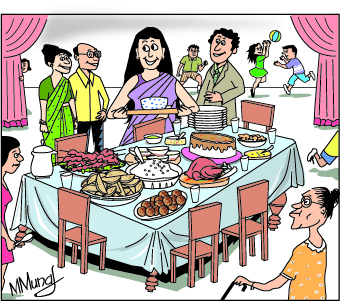

She was a quiet one: fair, beautiful with a mane of frizzy black hair. I would have loved to have her curls because my hair is ordinary wavy. Hers is still the most perfect nose I have ever seen. It took many nights of sleeping in tight alice bands to realise that my pointy daddy ears would never be like her tiny beautifully-shaped crescent ears, perfectly positioned against her head. I’m glad she had bright moments. How on earth did she do it, I wonder often, remembering not just the three or four meals a day but birthday parties, Christmas parties, and the New Year’s Day parties. How did she cope with the irate tuition teachers who walked into the water bucket and stink bomb booby traps we kids set up for them. We came to expect it of her. Didn’t she get bored with chores? I feel bad about the troubles I caused. Her life could not have been even remotely easy – not with such a vast household to run. She taught me selflessness, resilience, patience and love.

Later, mum retired. Her nest fell apart. We dispersed. Now she tends her garden. These days, the old fashioned housewife is rare if nonexistent. She has receded into the shadow of the modern, working woman. I can only marvel at the miracle of the woman mum represents. Often unpaid or underpaid, unappreciated, forgotten, underestimated, taken for granted, she had skills that few of us would dare consider. Thank you beloved mum for all that you are and have been.