Sunday Times 2

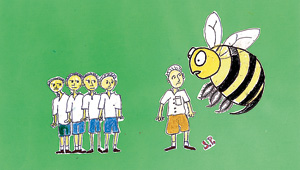

The sting of the Spelling Bee

Get a big but unfamiliar word wrong in front of a crowd and you will carry the embarrassment for the rest of your days, writes Stephen Prins

Ever wondered what it feels like to be shamed by a word, in public, for all present to witness your embarrassment? We speak not of a shameful, shaming, ugly word, but an eminently respectable, though thoroughly unused word. Permit us to share an unpleasant experience we had with a word that should have been a friend, an ally, but failed us on the one occasion it stood before us. Or did we fail the word? That’s how others might see it.

PUBLIC SPEAKER: Look hard. This is the first and the last time you will see this word. CITIZEN: So why show it to us?

On with the story, the word, and the story around it. Like many of the words we use, the word in question that popped up one dismal day in 1965 is old as the Roman Empire, Latin to the core. It used to appear in popular pocket English dictionaries up to around 25 years ago, and then it started to fade out. It is one among hundreds, thousands of words that rarely appear in everyday print and almost never in conversation. It was or is the kind of word favoured by fusty academics, and those who adorn their conversation with Classical allusions and quotations.

Our first and only face-to-face encounter with the word was in the time we and our peers were growing our first moustaches and aiming to impress in every way – impress ourselves, our classmates, parents, teachers, school rivals, and the rest of this needlessly competitive world. The word in question would cost us something – something important in the departments of school name and honour, peer-esteem, and self-esteem. That’s a lot for a single word to hold responsibility for.

Four-and-a-half decades later the word remains lodged in our system like an inoperable linguistic cyst, and in the head like a benign tumour. It feels like a “majithi” seed, and like a majithi seed it is hard and bright red; its hard, shiny enamelled shell would require a sharp tooth or nail to crack.

Our failure, aged 15, to crack the word, and the consequences of that failure, is the burden of our story.

That year we were on the school team for an inter-collegiate Spelling Bee. Over the years the school had done well in the competition, winning or coming second, or at least surviving into the final round. The contest was held at Radio Ceylon, Buller’s Road, Colombo 7 on an education programme that was broadcast live to the whole country. Those who had a reputation for good spelling, who could handle tricky words like “exacerbate” and “surreptitious” and fulsome words like “quotient” and “ostentatious”, qualified to join the five-member team. Language teachers familiar with their students’ written work – from test essays on patriotism and colonial oppression and descriptions of school life and life on other planets – nominated the team members. To be part of the team was, of course, an honour.

It was a bigger honour to be team captain, a lot that fell to the nerdiest of the five members that year. (This was long before the “nerd” word came into use.) If you wore thick eye-glasses and chose your words carefully, you had a good chance of being nominated captain. If, in addition, you wore voluminous knee-length khaki trousers and a white shirt with unwashable ink stains on the pockets, your chances were greater. Between 1963 and ’65, we possessed all these attributes, personal and sartorial (there’s a good seldom-used word, befitting a spelling bee).

By way of background information, we might add that we collected words – the long, segmented, multi-syllable kind, squirming or fossilised – the way Older Brother and his aquatic pals searched the seas to collect shells and other marine curiosities, and Younger Brother and his classmates collected pre-World War I stamps.

That morning, on its way to Radio Ceylon, the team reminded itself that the school either won the spelling bee or came close to winning. If we lost to a girls’ school, the shame would be bearable, for girls were known for their easy ways with words. Girls used words more than boys did; girls were chatty and garrulous, wrote good essays, and spoke eloquently at speech contests and debates. Boys trailed a bit in the verbal arts, but for the team to lose to a rival boys’ school in a spelling bee was unacceptable. Correction: Unforgivable.

To cut to the chase (a cinematic term then not current that means “let’s get on with the main story”), we strode into the Radio Ceylon recording hall with excusable confidence. The seats were filled with teens in white uniforms and their saari-ed and suited teacher chaperones. All hailed from leading Colombo boys’ and girls’ schools. The general facial expression in the hall was combative, not pleasant. We, in contrast, smiled, bowed and took our seats.

The master of ceremonies was a short plump person in shirt, tie and baggy belted trousers who had to be a boy’s school teacher. He walked up and down the aisle holding a microphone with a trailing cord the way some fathers carry a belt and some teachers a cane – threateningly. He warned us not to talk or even whisper, because “every little sound carried” in a radio broadcast. We could open our mouths only when the microphone was held to our faces. On the stage was another solemn, unsmiling teacher-type who introduced the teams, announced the rules, and called out the words for spelling.

Prompting was forbidden. A contestant had 10 seconds to spell out his or her word; if he or she got it wrong, someone else in the team, usually the captain, was given the team’s second chance: one point for first correct answer, half a point if the second answer was right, and three bonus points to any contestant in the hall who had the answer.

To a side, behind a glass screen in a box of a room crowded with consoles and recording equipment was a familiar smiling face, the only smiling adult in sight. It was the tall, gaunt, spectacled Mr. Livy Wijemanne, a senior presence at Radio Ceylon. He was a classmate of Father’s in the Thirties and an organiser of classical music radio concerts that Mother was involved in during the Forties, Fifties, and Sixties. That one pleasant relaxed face was deeply reassuring.

To a side, behind a glass screen in a box of a room crowded with consoles and recording equipment was a familiar smiling face, the only smiling adult in sight. It was the tall, gaunt, spectacled Mr. Livy Wijemanne, a senior presence at Radio Ceylon. He was a classmate of Father’s in the Thirties and an organiser of classical music radio concerts that Mother was involved in during the Forties, Fifties, and Sixties. That one pleasant relaxed face was deeply reassuring.

Earphones on his head and seated penned inside a glass-fronted cabin, Mr. Wijemanne suggested another gaunt spectacled figure we had seen four years before in newspapers, magazines and newsreels; that hunched figure too sat inside a glass cell, a cage, though in that case the glass was bullet-proof and the chief occupant ghostly and ghastly. Unbidden, and quite inappropriately, images of the trial of Adolf Eichmann had come to mind. Of course, no two persons and situations could have been more different or far apart. The subliminal suggestion of a courtroom trial came from both the figure in the glass enclosure and the judges and spectators inside the hall. It was a strange sensation, and it deepened as the spelling bee advanced; the climax, or rather anti-climax, for our team in the proceedings confirmed a weird sense of being trapped inside a nightmare courtroom.

The contest got underway. Our team performed well until the fourth member got a word wrong. The stumbling block was one of those official-sounding “EX-” words, the kind you might hear during readings for new laws passed in Parliament. Stoutly, the captain of the team stood up and started to spell the word. It was a word he could not remember ever hearing or seeing in print. It sounded like “temporary,” “contemporary”, “exemplary”, three words he used for guidance.

In fairness to the captain, it was a word he may well have previously seen, while skimming the EX columns in his Oxford Pocket Dictionary; he might have flitted past the word looking up scare terms such as EXCORIATE and EXCOMMUNICATE.

“E. X.,” he began on a strong note, “T. E. M. P. O. R. …” (so far, so good) . . . “Y”.

Silence.

“WRONG!”

An acidic smile modified the moderator’s fleshy face.

“Wrong,” he said again, loud and redundantly into the echoing sound system.

“Where our contestant inserted a Y,” he said accusingly for all present to hear, “there should have been an E!” A tinny note of triumph vibrated in the sound system.

“E. X. T. E. M. P. O. R. E. That’s the correct spelling,” he continued, and without even stopping to define the trip-up word, the moderator moved on to the next school. Everyone in the hall looked smug and knowledgeable, as if “extempore” was in their daily vocabulary. With shame burning and buzzing his ears, the captain of the team did not stop to note whether the word was picked up by anyone else in the hall.

For the record, EXTEMPORE means speaking or doing something without preparation, and is pronounced as if the last letter was a Y. The word is built out of Latin terms that mean “on the spur of the moment.” IMPROMPTU is a frequently used word that means the same thing.

That one misspelled word eliminated us from the final, which took place after lunch. As always, the finalists were the two schools that had shown the sharpest spelling bee proboscides (now there’s a fine science word for such a contest). Outside Radio Ceylon, the team members turned on the captain. They told him, with the solemn expression of jurymen in a court of justice, that he had killed the school’s chances of winning the contest, and that this was the first time in the school’s history that its spellers had not made it into the final. Sentence delivered, they strode off.

The captain hung his head in shame, charged and found guilty in the Court of Eminent Unfamiliar Words. He hung behind until the rest of the team had turned a corner, then followed with heavy heart and dragging feet. In the 50 years since fumbling “extempore”, the captain of the team cannot recall ever seeing “EXTEMPORE” in print, not in large or small font, or hearing the word uttered, muttered, shouted or whispered. Not once.

Until, of course, he checked the print proof of the story that you, Dear Reader, have just read.

(This is the second in a series of articles on the written, spoken and unspoken word)