News

‘We are fishermen – we do not see borders’

A baby sleeps peacefully in a cradle made with a saree hung from the roof of the cadjan hut. It is a small house with a single bedroom, a living area where the baby is sleeping and a kitchen in which an elderly woman in her late seventies is waking from her afternoon nap.

We are in Rameswaram, Tamil Nadu, in a village locally known as Verkadu, after an exhausting journey of 20 hours in a train from Kottayam, Kerala to Coimbatore and a night bus from there.

The docked trawlers

Rameswaram, an islet just 50 km away from Sri Lanka’s Mannar Island, is a refuge for pilgrims who visit the famous Ramanathaswamy temple, a holy place for Hindus. It seems a place where people lead tranquil lives but is the centre of a tense struggle for the right to fish in Sri Lankan waters in search of a better catch.

At the little cadjan house that belongs to fisherman J. Thomas we are welcomed courteously. He smiles humbly as his wife places small glasses of soft drinks on the floor for us. His youngest daughter sits on the floor with her eyebrows knitted in thought as her father speaks.

“Fishermen find it hard to support their families now after Sri Lanka banned us from fishing in her waters,” Mr. Thomas said. “Several years ago we fished in the sea between Sri Lanka and India, not concerned about any borders. We are fishermen – we do not see borders – but now we are burdened by them.”

His family is one among 2,500 others in the area affected by the unsustainable decisions the Tamil Nadu Government made several years ago by allowing bottom trawling (a method banned in Sri Lanka and many other countries) and use of the minuscule-hole fishing nets in Indian waters, which sharply depleted the fish population.

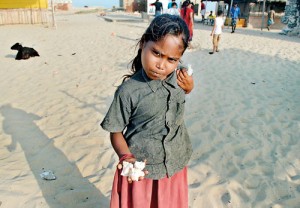

A fishermen’s daughter sells seaschells to tourists

According to the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI) in Kerala the marine fisheries sector is the crucial contributor to Tamil Nadu’s economic development, with 591 marine fishing villages and about 10, 692 mechanised units and nearly 25,000 operating units, both motorised and non-mechanised, engaged in fishing.

B. Sesuraja

The CMFRI also shows that there are nearly 200,000 fishing families in the state and that in the last year on record, 2011-2012, Tamil Nadu’s marine catch was an estimated 630,000,000 tons.

“The mechanised and the motorised sectors contributed between 75 and 24 per cent of the total landings respectively while the non-mechanised sector contributed only 1 per cent,” it stated.

There are more than 2,000 trawlers in Rameswaram and fishermen are not discouraged from going bottom-trawling in them, with the government giving them subsidised fuel for their boats and funds for maintenance.

The Indian part of the Gulf of Mannar has been declared a Man and Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO but this has not stopped the fishermen from trawling in the area. Studies have shown that the coral reef that is damaged by this practice takes decades to restore.

The Rameswaram fishermen argue that this is not the case. They believe that after they fish the sea mud with roe gets washed out of the nets back into the sea.

J. Thomas: “Fishermen find it hard to support their families now after Sri Lanka banned us from fishing in her waters.”

S. Sahayam

“There could be some scientific truth in the negative outcome of trawling but we should also see that in the 2004 tsunami the marine population was badly affected, and some of it was destroyed. Trawling is not the only reason why the fish are disappearing,” B. Sesuraja, 47, the Secretary of the All-Mechanised Boat Fishermen Association and a third-generation fishermen, said.

He also pointed out that the Tamil Nadu Government has banned fishing from April 15 to June 1 so that fish could freely mate. This would restore the fish population, Mr. Sesuraja said.

Yet, with the decrease in fishing yield in their own waters the Tamil Nadu fishermen now blame the shallow and rocky seas around Rameswaram for low catches and are urging permission to fish across the International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL).

S. Sahayam, 48, the president of Saint Saviour Fishing Association, one of the 11 fishing associations in Tamil Nadu, said it was impossible to get a good catch on their side of the Indian Ocean because big fish do not grow in shallow waters.

These fishermen are also drawn to Sri Lankan waters for its abundance of prawns, that have a good market in India, and sea cucumber – a catch declared illegal by the Sri Lankan government. On March 24 an individual who tried to fish for it was arrested by the Sri Lanka Navy off Pannai, Jaffna.

Rama Moorthi

Indian fisherman Rama Moorthi, 55, who has been a seaman for the past 40 years, says that when his boat went trawling across the IMBL he was able to catch at least 25kg of prawns on the Sri Lankan side. This, he said, was enough to support his family for weeks.

“Now we are restricted in our main source of living. We do not know whom to turn to. When we go to the Tamil Nadu politicians they ask us to fish as we want but when we cross the boundary the Sri Lanka Navy arrests us,” Mr. Moorthy said.

On March 21, 54 Indian fishermen were arrested for poaching in the seas off Kankesanthurai and Thalaimannar. On April 3 the navy arrested 37 Tamil Nadu fishermen for illegal fishing. Most of the arrested fishermen and trawlers taken into custody were released in batches during the past few months, including 86 who were repatriated as a gesture of goodwill during Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Sri Lanka in March.

The Rameswaram fishermen were not happy when they got their trawlers back, saying the vessels had been heavily damaged by sea wind and rust, causing losses worth millions of rupees.

B. Suvi, 29, a father of two, is one of the fishermen who were held in Anuradhapura prison and later released. His trawler was also given back to him but its engine needed to be repaired and the wooden planks had rotted, he said.

“I pawned my wife’s gold jewellery and took a loan from the bank to buy this trawler. I couldn’t even pay the loan or save the gold. To go back to fish I will have to repair my boat and that will cost me at least (Indian) Rs. 200,000. I can’t afford it. I have nothing now,” he said.

Meanwhile earlier this year, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister O. Panneerselvan called for India to reclaim the islet of Katchatheevu and restore the historic fishing grounds of Palk Bay to Tamil Nadu fishermen. Sri Lanka gained ownership rights to Katchatheevu from India in 1974.

In another bid to aid these lamenting fishermen the Indian Government held a meeting, the third of its kind, in Chennai on March 24, when the Tamil Nadu fishermen forwarded a proposal to fish in Sri Lankan waters for 83 days each year. Although they had high expectations that their counterparts would agree to their terms, the Sri Lankan government rejected them, causing an uproar in Tamil Nadu.

A delegation of fishermen met India’s External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj in Delhi on April 29 to plead their case. She had asked for a few days to resolve the matter.

“She said that President Maithripala Sirisena has opposed our proposition because the fishing population voted for him. She warned us not to cross the border and wait till they hold further discussions to give us a favourable solution,” Mr. Sesuraja said, adding that he put it to the minister that the Indian government should take the trawlers and give them money to start new occupations.

The failure of both Indian and Tamil Nadu governments has caused these fisherfolk to seek solutions elsewhere.

N. Devadas, President of the Rameswaram Fishermen’s Association, said that more than 100,000 fishermen from Pondicherry to Rameswaram have lost their jobs as a result of this situation which began worsening since the end of last year.

Some have started to fish in the seas of Kerala, Andhra, Orissa and Gujarat.

“Fishing in our countries has taken place for generations,” Mr. Devadas said. “Before the Sri Lankan ethnic conflict we used to fish in harmony.

“There are enough fish for both parties in this sea. We need permission to continue what was our tradition,” he said, insisting that Sri Lanka’s waters did not belong to Sri Lanka but to both countries.

While the governments of both countries are tussling over the matter, fishermen of Rameswaram stay grim and helpless.

Mr. Thomas, who does not go fishing these days, said he does not want his children to enter the profession but, he said, they need time to move into another line of work.

“We can’t stop fishing overnight and we can’t stop trawling either. This is all we know to do. To learn something else we need at least three years. We plead with the governments to understand our situation and give us these three years,” he urged.

| Lankan navy ‘uses stingray torture’“One-and-a-half years ago my son went to sea but he never returned,” said 49-year-old Fathima Mary from Rameswaram. Holding up a photocopy of a news article about her son’s last encounter in the Indian Ocean, Ms. Mary accused the Sri Lankan Navy of being responsible for her son’s death. The son, a father of one, had gone fishing with five others from his area. Only four of them came back home. They said the Sri Lankan Navy had surrounded their boat and rammed it, causing two deaths, an allegation constantly denied by the navy. The incident caused an uproar in Rameswaram. “We are innocent people. Our children can only fish and this is what they know. The Sri Lankan Navy is murdering our children who are only trying to put a meal on our tables,” the mother cried. Other fishermen who encountered the Sri Lankan Navy in Sri Lankan waters claimed they were sometimes tortured before being released with a warning. They said they were pricked with stingray tails and even burned. Today, Ms. Mary lives alone and sells food such as idli to tourists to earn a living.  Fathima Mary holds up a newspaper cutting about her son |