Fantasy, fable and reality; all in one

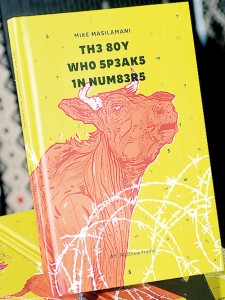

While deep in conversation with Mike Masilamani about his book, there were times where I almost expected the book’s small, insignificant looking protagonist to shyly sidle up to our table and join our discussion. When Mike speaks of his book ‘The Boy Who Speaks in Numbers’, he matter-of-factly refers to it as ‘The Boy’. Soon, the book’s paper and ink character takes on a curiously lifelike quality. A nameless boy, to whom numbers come easier than words, the boy faces the perennial struggle of childhood – the attempt to make sense of the nonsense in an adult world.

The boy’s story has resolutely withstood the trappings of time by mutating into different genres over the years. First written as a short story for a children’s magazine, the plot was then kneaded into a play – The Travelling Circus– which was performed in Colombo in 2009 to mixed  reviews.In its most recent avatar, ‘The Boy Who Speaks in Numbers’ is a slim novella brimming with poignant illustrations and is a darkly satirical look at conflict through a child’s gaze.

reviews.In its most recent avatar, ‘The Boy Who Speaks in Numbers’ is a slim novella brimming with poignant illustrations and is a darkly satirical look at conflict through a child’s gaze.

I meet Mike along with his editor, V. Geetha from Tara Books on the day of his book launch in Colombo earlier this month. With Mike based in Australia, the book’s illustrator in London and Geetha in India, both writer and editor have met for the first time only the day before, despite many months of collaboration. By now, both have slipped into the kind of easy familiarity which two years’worth of trailing emails, deadlines, debates and creative tussle inevitably bring and our conversation is peppered with book banter and stories behind the boy’s journey. Now that ‘The Boy’ has been cautiously sent out into the world to find his own legs, both writer and editor have already embarked on their next writing project together.

With advertising in his blood (quite literally, as his family runs an advertising agency in Colombo) Mike’s early writing took the form of pithy copywriting. As a reaction to advertising, Mike sought refuge in writing poetry and for a brief time wrote under the pseudonym Masii. The Boy’s story began as an artist’s antidote towards all the violence rupturing the island during the last stages of the war. Mike confesses that he lost faith in poetry and began internalising the disquiet he was feeling through his protagonist using prose. In the context of the violence swelling around, war rhetoric and fear, the boy’s naiveté provided a welcome counterfoil to real life. The boy’s story was initially written for a discerning audience of two (Mike’s children) and uses metaphor and allegory, giving it a fable-like quality and has considerably evolved from its previous reincarnations.

Fruitful collaboration: Editor V. Geetha and author Mike Masilamani. Pix by Amila Gamage

Set in the Island of Short Memories, the Boy who Speaks in Numbers provides a stark satirical portrait of the Civil War of Lies and the havoc it wreaks on the Small Village of Fat Hopes. When his village is caught in the line of fire, the Boy accompanies other IDPs (Ignorant Disillusioned Persons) into the Kettle Camp. The Kettle Camp is ruled by an important Aunty armed with an aversion for questions (her face erupts into pimples upon being confronted by uncomfortable queries) and a group of unctuous peons. The Constantly Complaining Cow, the Kind Uncle and the Lying Lizard from the Ministry of Internal Revisions (incidentally a skilled liar and in possession of chameleon-like qualities) are some of the bevy of characters who traipse in and out of the book’s pages and are brought to life through the skilled hands of the book’s illustrator, Matthew Frame.

“For Tara Books, what was attractive was the child protagonist. That’s something we feel is a very powerful thing – to understand war through the eyes of a child. Not for nothing is the diary of Anne Frank still very popular,” explains Geetha from an editorial perspective. The war described in the book is not coloured by any ideological notions but viewed through the lens of its child narrator, depicts what Wilfred Owen referred to as ‘the pity of war’. Readers from Sri Lanka will instantaneously recognise certain details in the story but otherwise, it has been carefully crafted to sidestep immediate local detail to avoid diluting the story.

What is noteworthy is the manner in which Mike raises uncomfortable social truths which many people become immune to when living in conflict, in a seemingly casual way. Be it the crudity of advertising on checkpoints, joking references to white vans, war as a commercial exercise, unwitting complicity or a noncommittal offhandness about the numbers involved in the war. “Did we really turn into the kind of people we did?” muses Mike. “To me there was always this niggling suspicion that if we did what we did, we can very easily do the same. What has changed to prevent us from going back? It’s amazing how easily we descend into a mindset of violence and become blasé to the whole thing[…]And that’s where the reference to numbers came in. We started getting increasingly casual about the whole thing. That was not something I was necessarily comfortable with.”

The book doesn’t offer neatly wrapped endings but instead raises questions and blithely eludes concrete answers.It isn’t easy to write about war while avoiding descending into a vortex of darkness but the Boy who Speaks in Numbers evades this through its use of allegory and the absurd, and setting its scenes in the outlandish world of fable and fantasy. Bringing a child’s perspective to the horror of violence makes us turn the gaze inward, if at least for a bit.The book resists being pigeonholed into a genre – the story is deceptively simple enough for a child to understand and enjoy but at the same time, both text and illustrations contain a depth attainable only to an adult. The book’s illustrations deserve mention for their juxtaposition of bold colours, quiet attention to detail and amplification of the narrative.