Was Dutugamunu inspired by Asoka?

It was on a Poson Poya Day in 236 BCE that Emperor Asoka sent his son Mahinda Thera to Sri Lanka to establish the Buddha Sasana which took root with the wholehearted patronage extended by the Lankan ruler – Devanampiyatissa (250- 210 BCE.)

Barely 40 years after Devanampiyatissa however, the Buddhist Doctrine disappeared from Anuradhapura with horse-traders, Sena and Gutthika and later Elara from South India usurping the Lankan throne during the brief reigns of Devanampiyatissa’s four brothers and ruling for 64 years. The chances were that the Buddha Sasana would disappear altogether had Dutugamunu (161-137 BCE) not defeated Elara. Dutugamunu’s presence therefore, was the need of the hour and he himself spelt out his mission thus: Not for the joy of sovereignty is this toil of mine. My striving has been ever to establish the Doctrine of the Sambuddha. (Mahavamsa).”

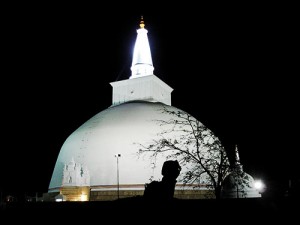

Ruwanveliseya: Dutugamunu’s jewel in the crown

With the conquest of Rajarata, Dutugamunu revived Buddhism taking it to the loftiest heights ever in Sri Lanka.

Dr. P.G. Punchihewa, retired civil servant/author and State Literary Award winner in his book “King Dutugamunu – The Commander-in-Chief” credits Asoka, Devanampiyatissa and Dutugamunu as the three monarchs responsible for the establishment of the Buddha Sasana in Sri Lanka. While he states that Asoka and Dutugamunu shared certain similarities he poses the question whether Dutugamunu was inspired by the latter part of Asoka’s life?

Asoka reigned about hundred years before Dutugamunu and was the first King to bring the entire India under one rule. Although the area of military operation was smaller, Dutugamunu was the first ruler to fight invaders and unify Sri Lanka.

Asoka the conqueror however, unlike war heroes such as Alexander, Julius Caesar, Napoleon, George Washington, Churchill et al ….. was stricken with grief after his final annexation of Kalinga. A rock edict reveals “The beloved of the Gods, the conqueror of Kalinga is moved with remorse. For he had felt profound sorrow and regrets because the conquest of people previously conquered involved slaughter, death and deportation.” Asoka eventually found solace in Buddhism.

Recalling the destruction of thousands of men during the battle, Dutugamunu according to Mahavamsa, was grief stricken and was unable to sleep. Eight Arahats who arrived at the Palace consoled the King and as asked by them he observed the Buddhist Precepts. Eight more monks learned in Abhidhamma, recited “CittaYamaka” and the King fell asleep.

Dr. Punchihewa who quotes eminent writers to throw light on historical events cites Professor Dhammavihari. “Dutugamunu’s encounter with Elara does not compare with Asoka’s Kalinga war. For Asoka, it was “digvijaya” – the endless pursuit of a policy of aggrandizement to which he had to call a halt at some suitable point. “ Whereas, Dutugamunu’s action was the fulfilment of the obligation of a ruler to the state. When he visited the Sangha at Tissamaharamaya to receive their blessings before he set out for battle, Dutugamunu told them that “he is going across the river (Mahaveli) to bring glory to the Doctrine. (MV)”. On his request, he was provided with 500 monks to accompany the army. While on the march to Rajarata, the retinue stopped over at Mahiyangana, raised the dagoba up to eight cubits – acts which enhanced the confidence that his mission was to protect the Sasana.

However, as Dutugamunu advanced, his capture of the 24 fortresses resulted in the loss of a substantial number of men, forcing him to replenish the army with fresh recruits from the south. When in direct combat with Elara, the battle at Kasagala was so fierce that the water of the tank turned red with the blood of the slain. With the enemy in disarray, it would have been possible for the Ruhuna soldiers to chase after Elara and put him to death at which point, Dutugamunu had declared “none but myself will slay Elara (MV).”

“According to the Kshatriya code,” the author quotes Professor Paranavitana, “there was nothing so dishonourable as not to fight when challenged in battle by the opponent of equal rank. Elara accepted the challenge and the duel followed.”

The author views the reaction of the conqueror towards the vanquished as an act of reconciliation after freeing the country. Two writers had this to say, “world history does not record of any victorious ruler showing such magnanimity to a fallen foe.” And “that was the finest hour of Abhaya Gamini, the greatest Sinhala King.”

Dutugamunu ordered people from yojana (16 miles) to attend Elara’s funeral. “On the spot where his body had fallen, he burned it with a catafalque and there did he build a monument and ordain worship. Even to this day, the princes of Lanka when they draw near to this, are wont to silence their music because of this worship.” The promulgation according to Saddharmalankaraya read “members of the royalty when passing this place should dismount their elephants, horses, palanquins and litters.” The rule specifically mentioned that it applied to Dutugamunu as well.

The edict had been honoured as late as the 19th century according to Major Forbes’ “Eleven Years in Ceylon.” Dr. James Rutnam’s “The Tomb of Elara” which he wrote for the Jaffna Archaeological Society in 1981 remarked “The respect, indeed the reverence extended by Dutugamunu to his fallen enemy Elara, the righteous ruler, is surely unique in the annals of the island’s history.” The magnanimity may have surely extended to the rest of the subjects!

With the battle over, Dutugamunu, just as Asoka with his conversion to dharmavijaya, devoted his energies during his 24 year-reign to advance the cause of Buddhism. Englishman William Kinghton saw it in his “History of Ceylon” as “his happiness consisted not so much in reaching the goal first as in running the race. When the race in one place was concluded, it was but to commence it elsewhere.”

Dutugamunu is credited with the construction of Mirisavetiya, the nine-storeyed Lova Maha Prasadaya – a magnificient monastery for the Sangha and 99 temples. His jewel of the crown was Ruwanveliseya about which Thupavamsaya (14th century) wrote: “The Mahathupa speaks eloquently of the boldness and daring which were the outstanding features of Dutugamunu’s character. For in his day, a monument equal or approaching it in size existed nowhere in the whole of the Indian world.” Dutugamunu thus launched the tradition of massive-sthupa-building.

The news of Dutugamunu’s victory and efforts to revive Buddhism would have reached every corner of the then Buddhist world. Their keen interest was evident from the large scale participation from overseas for the ground-laying ceremony – an event in Lankan history, second in grandeur only to the planting ceremony of the Sri Maha Bodhi Sapling in Anuradhapura during the time of King Devanampiyatissa with Bhikkhus invited from as far as Rajgir, Vesali, Kosambi, Udeni, Bodh Gaya, Patali Putra and Kashmere. Mahavamsa even mentions names of Theras who arrived including those from the Land of the Greeks. The author suggests that this was the first recorded largest international congregation in the world to have been held. Mahavamsa also mentions the arrival of Bhikkhus for the event spread throughout the island “what need to speak of the coming of the brotherhood living here upon the island.”

Some of the welfare activities of Dutugamunu have much resemblance to those of Asoka as mentioned in his rock inscriptions. They included medical treatment for people as well as for animals, setting up of hospitals employing physicians at state expense and providing food for the expectant mothers. His orders included the provision of straw dipped in honey to appease the hunger of draught bulls which work during daytime.

Asoka however, was responsible for the spread of Buddhism outside India which elevated it to the status of a world religion. Dutugamunu’s role was given poignantly by Theraputtabhaya Maha Thero who declared thus at his deathbed. “The setting up of sole sovereignty by thee did serve to bring glory to the Doctrine.”