Sunday Times 2

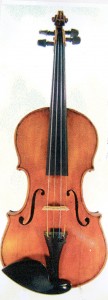

The Grancino

Goingback many years, whenever Eileen Prins talked about her precious long-gone Grancino, she would grieve. She was remembering a beloved child, a baby, really, one she had once hugged closely and lost, had embraced passionately and been forced to let go of. Heartache, heartbreak spoke in her voice.

The exit of the precious 17th-century Italian violin that had sung so exquisitely to family and music lovers left an aching void, an emptiness understood only by someone who has said a final farewell to an intimately loved one. Mother never really got over the loss of that child of hers, her first, delivered to her hands in 1940, when she was 22 years old, a scholarship student at the Royal Academy of Music, London. World War II was well under way.

Professor Sydney Robjohns, Eileen’s mentor at the Royal Academy of Music, wanted his student to have a superior instrument. They went to the famous string instrument dealer, W. E. Hill & Sons, at 38 New Bond Street. Eileen tried out several violins, and she and the professor settled for a 1693 Grancino. The dealer listed the violin’s virtues and value points, adding that the distinguished German concert artist Ida Haendl had once played on the instrument.

The tone of the violin spoke to Eileen. Also, it was just right in dimension, a little smaller than full-size. Eileen was petite at five feet three, and the Grancino was diminutive at 7/8 of the standard. It cradled to perfection in Eileen’s arms.

Eelien Prins: The first Ceylon student to win the Government Music Scholarship in 1939. She spent five years at the Royal Academy of Music in London where she held the post of sub-Professor for two and a half years prior to her return to Ceylon. Inset a 1703 Giovanni Grancino violin

The trouble with the Grancino started not long after Eileen and Deryk Prins returned to Ceylon, in 1945. Prof. Robjohns had hinted that the tropics might not be the best for the ultra-refined, hyper-sensitive Italian baby. But violin and violinist were inseparable, and would stay together for another 10 years after returning to Ceylon. The violin would become an extension of Eileen’s singing soul. The first of four siblings, the Italian baby was already 250 years old when it joined the family.

The story of the Grancino was, like all Eileen’s stories, moving and wonderful. You never tired of hearing it, along with the rest of her stories of life in London during the War. The Grancino narrative started as a war story, beginning in England, around the time Churchill was directing British forces to enter Ethiopia, and concluding in Ceylon 10 years after the War had ended. Eileen was eloquent and thrilling to hear as a violinist and a storyteller.

On her return in ’45, Eileen, housewife and soon to be a mother, had all but given up violin playing, although she had a few music students, one being the future concert pianist Malinie Jayasinghe-Peiris. The local music community was asking what had become of Eileen Prins, the double-scholarship winner who as a teen had year after year topped the list, beating violinists and pianists with the best marks at both the Royal Associated Board and Trinity College music examinations.

Then one day Eileen was approached by a friend and music colleague who had also studied at the Royal Academy in London, a few years earlier. The pianist Irene van der Wall was keen to play sonatas with Eileen. She also persuaded Eileen to join the Symphony Orchestra of Colombo, which was coming together at the time. The Grancino was taken out of its case, tuned, and made to sing. Sing it did, exquisitely, to the joy of its  owner and all who heard her.

owner and all who heard her.

Eileen Prins and Irene van der Wall rehearsed regularly, at each other’s homes, and gave broadcasts over Radio Ceylon. They played Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Cesar Franck, Edward Grieg, Delius. They made a great duo. Father said Eileen and Irene were the best classical music partnership he had heard in this country.

In the meantime, we would scamper past the music or sit on a cool tiled floor and listen to classical and romantic sonatas. We were not yet ready for Montessori, but we were enjoying Mozart. We had ears to hear with. We must attribute our enduring interest in Bach, Beethoven, Brahms and the rest to those early years of eavesdropping on two musicians practising away for hours in the resonant hall at Weimar, the family home.

Soon, Eileen Prins was in the public eye as leader of the new Symphony Orchestra of Colombo. After one resoundingly successful concert at the Lionel Wendt, in which Eileen played the solo violin part in the Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, in D major, she was greeted backstage by Tori de Souza and his wife Audrey, both musicians. Tori, who was editor of the Times of Ceylon, was in raptures about Eileen’s performance. He asked about the violin. Eileen held it up, like a mother holding and caressing a child. She gave it to Audrey and Tory to hold. “Do you feel her breathing, speaking?” Eileen asked. They did. The delicate instrument was vibrating in their hands in sympathy with the sound of their voices. “No violin I have ever held speaks like my Grancino,” Eileen said.

Maker’s name and year of make are visible through a narrow slot cut in the wood of the front panel of any string instrument. You peer through one of the long narrow breathing apertures, the f-holes, to find the instrument-maker’s label, glued to the inside of the instrument’s back piece. This label is of great importance and interest, especially in old instruments.

Going back in time

We have the faintest memory of Mother tilting the Grancino to the light so we could see the violinmaker’s name, traced in elaborate old-style lettering. More exciting was the “1693″, traced in ink that might have once been black but was now a pale coffee brown; the label was the colour of the wood to which it was affixed. Aged five or four (or was it three?), you were not too young to understand the significance of what had been placed in your hands; not too young to sense the excitement of history in that moment.

Pressing your face to the violin, peering at the label of proof under a film of dust, you slipped like a ghost into 17th-century Italy.

Bright morning in 1693. – Inside the Milanese workshop of Giovanni Battista Grancino, violinmaker. – Grancino family and apprentices bent over tables, bringing violins into the world. – Dust motes quiver in shafts of sunlight coming through long windows. – Air heavy with scent of sawn and shaved maple wood – of glue – resin – varnish. – Sawdust thick on the floor. – If only we could get in – climb in – slip into a Milan studio – for just one hour – one morning in 1693.

It. He. She. How do you refer to it?

Like all musical instruments, the Grancino was androgyne, neither male nor female, but containing characteristics of both sexes. It could be lyrical and tender like a daughter, or commanding and no-nonsense like a son. But mostly it was a sweet, singing thing, inanimate yet profoundly animate in a mysterious quasi-human sense.

Trouble in the tropics

The journey to the East was the Grancino’s first outing south of the Mediterranean, east of Suez. To Eileen’s dismay, the heat and humidity of Ceylon did finally undo the violin. Unaccustomed to anything but Northern climes for two-and-a-half centuries, the instrument reacted adversely here. Her joints swelled and she started to come apart at the seams. She would be put back together by expert local hands only to succumb again months later. They said the instrument was too delicate, too valuable to be tinkered with here. This went on for 10 years. Eileen wrote to Hill & Sons for advice. Hill & Sons wrote back, suggesting the violin be sent over to be “tropicalised.”

The tropicalisation of the Grancino became a big domestic issue.

Those were the days of ships. Deryk Prins’ Aunt Bessie was due for a trip to England and was happy to take temporary charge of the Grancino.

Violin in hand, Elizabeth (Spittel) Walbeoff went up the gangway. The ship’s captain said he was honoured to have a violinist on board, and invited her to perform for passengers and crew. Bessie, who was carrying a violin for the first time in her life, smiled and said she would think about it.

The Grancino was duly taken to Hill & Sons, who wrote back to say that “tropicalising” could endanger the violin, which would be better off permanently in Europe. Tropicalising was no guarantee the instrument would not buckle again in a hot-wet climate. Hill & Sons offered Eileen a deal – they would send her two violins in exchange for the Grancino. With the greatest reluctance, Eileen accepted the offer. Better her precious baby in good health in other hands, other lands, than in constant ill-health in Ceylon.

When Bessie Walbeoff returned from her UK trip four months later, she descended the gangway carrying on this occasion two violins. She had had an extra hard time on the voyage postponing indefinitely the concert the ship’scaptain, crew and passengers had been anticipating. She earned much respect on board as a “retired but shy, very retiring concert violinist.”

The two violins delivered in exchange were a 1765 Cuyppers, a Dutch make, and a 20th-century Hill violin. Together, they did not compensate for the gone grand Grancino. Such is life.

Eileen would feel acutely the pain of parting from the violin with the incomparable voice. She was in mourning. It went like a child taken away, never to be seen or heard again. It might have remained if the family could have afforded intensive care; the luxury of air-conditioning in those days was as remote as the planet Venus.

An able musician will bring out the best in a music instrument. When Eileen Prins surrendered her Grancino, she continued to make memorable music with the other violins she owned.

The sound of the word Grancino is almost compensation for the instrument’s loss. The name remains, it cannot be taken away. Grancino conjures hues of pale honey, pale gold, the shine of precious old instruments. Grancino has the crunch of double-stops and chords wrenched from the soul. To these ears, Grancino sounds grander than Gagliano, Guadagnini, Guarnerius.

Talking to violinists in America, England and Hong Kong, we would note eyebrows rising steeply at the mention of the Grancino. They all sang the instrument’s praises. There are Grancino violins, violas, guitars and double-basses.

A million-rupee option

The musicians also talked about the steep prices of Grancinos, which put them well outside the reach of any but the best-heeled of musicians, or poor musicians with affluent sponsors.

What Mother paid for the Grancino in 1940 is forgotten. A Giovanni Grancino violin, circa 1690-1700, topped a sale of rare music instruments at Bonhams, London, in October last year. It sold for Sterling 158,500, or US$$254,000, or Sri Lanka Rupees 33,118,600. Thirty-three million.

If the violin had remained in the family, and was finally sold only because there was no surviving heir worthy of it, what would we have done with our share of the proceeds? A searching, million-rupee question.

A couple of years ago, as one of a team on a goodwill visit to a deprived middle school in Rajagiriya, we were strolling around when we heard a faint high single-note of a sound, coming unmistakably from a violin. We peeped into a classroom. Sitting on a mat on the floor with his music teacher was a small boy learning to draw a bow across the strings. It was a sound and a sight we had heard and seen at home all our growing-up years.

If we had a couple of million rupees to spend, buying 1,001 violins for distribution among under-privileged schools would be a very tempting option.